Emperor Ai of Han was one of the earliest recorded examples of homosexual nobility and he ruled the Chinese Han Dynasty between 27 BC to 1 BC. Legend has it, one afternoon his male lover Dong Xian fell asleep on the sleeve of the emperor’s robe. The emperor was called to attend an urgent matter and rather than waking Dong up, he cut off the sleeve of his gown. Since then, “the passion of the cut sleeve” has become a Chinese expression for gay love.

Being lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning (LGBTQ+) has its challenges and obstacles anywhere in the world – but maybe they’re more pronounced in Chinese societies. Only a few decades ago, homosexuality was illegal in China; before 2001, it was listed by the Ministry of Health as a mental illness. Just like everywhere else, LGBTQ+ individuals in the region have had a challenging yet profound journey towards equality. These are the stories of seven of us from the Chinese community and our tales of coming out.

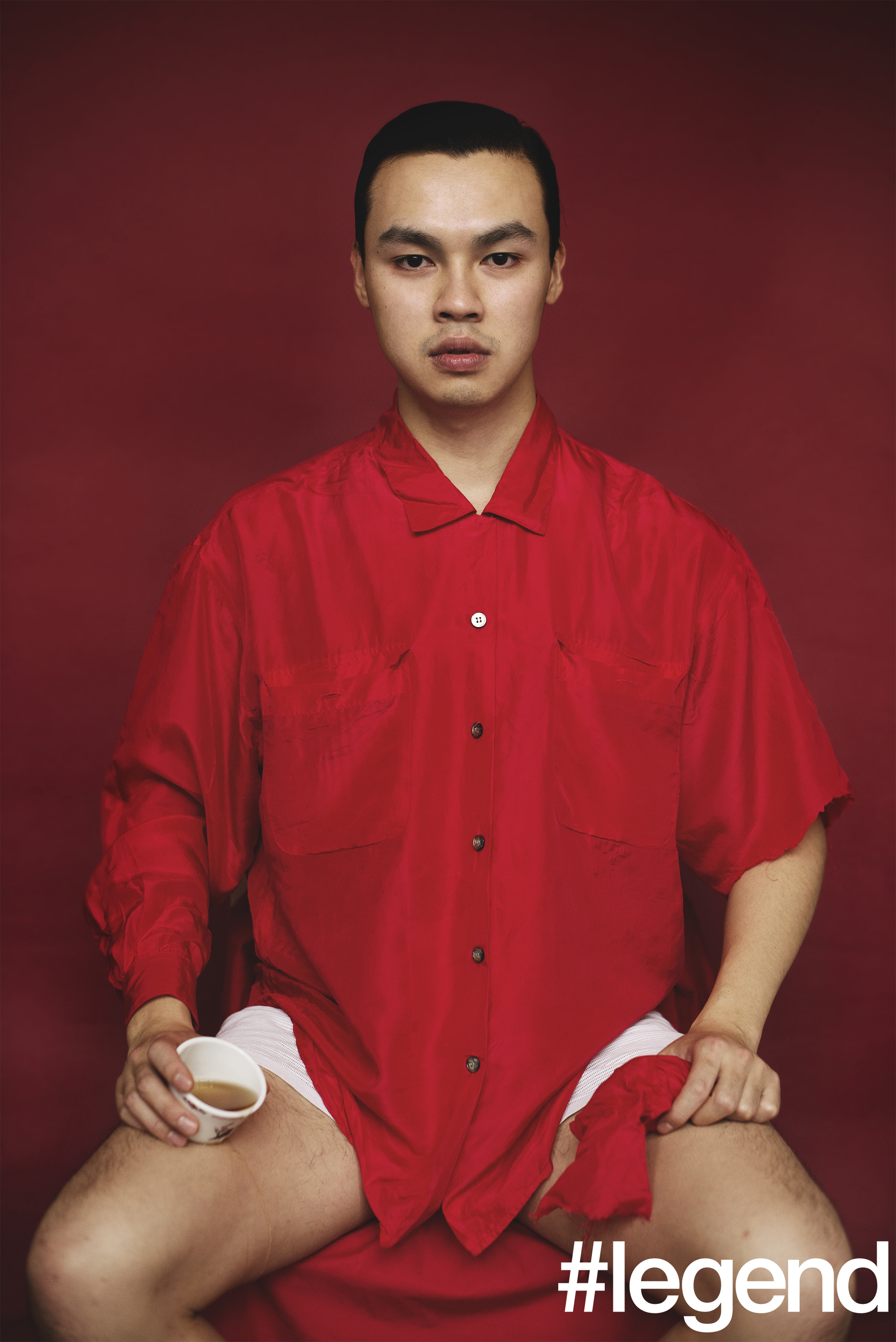

Kenneth Lam, Age 25 – My Own Story

At the age of six, my parents moved me and my siblings to a town called Northampton. We settled and my parents’ business flourished. School wasn’t easy; I was Chinese and I was gay, two things that were rare in my school. Growing up, I never really felt like one of the “boys” – I didn’t play football and I had a teddy named Pinky. Phrases like “You’re so girly!” and “Why do you act like that?” were often thrown at me by my friends, my brother and my cousins. At the time, I saw it as a negative, because just like most 13-year-olds, I was still trying to figure myself out. There seemed to be something shameful about me being like a girl, even though I was happy. It was a fear I didn’t understand yet.

High school was hard; friends came and went. Rumours spread around school and the bullying began. “Chinky”, “gay boy” and “fag” became uncomfortable background noise. That fear was now a reality. I wasn’t out, but to the rest of the school, I was. The sadness and anger gradually turned into motivation, and I left home to study in London. Unfortunately, my mother became sick during my second year. I prayed for the best, but by the time I graduated, she had passed. The grief turned into motivation to work even harder as I kept her in my mind.

Fast forward to 23 – I was in my first relationship, the bullying and ridicule was over, and I could breathe. I lived and worked in an environment that accepted and celebrated me. Yet I knew waiting at home were traditions and expectations. My father had always been proud of me, so his reaction to my sexuality meant everything. Determined, I decided to drive back to Northampton and tell him. But when the time came, I was silent. The fear was back. I thought, “If my mother could face the fear of death, I can face anything.” But nothing came out. It was my sister who helped me say the words – something I’ll always be thankful for. I finally uttered, “I’m gay.” He paused. He stopped looking at me. He turned his back on me and faced my sister. “He can’t be. It’s disgusting.” He went on. “He’s my son, I love him, but he has to change. He will never be happy.” He finally turned to me. “You’re never going be happy.” I cried.

I was shaking as I drove all the way back to London. For the first time in my life, I had done something my father wasn’t proud of. However, in my eyes, I had just been honest. I eventually understood his anger. His “golden child”, the one he had always praised, would never have a beautiful wife. There would be no Chinese wedding,

no grandchildren. I would never be truly happy. He was grieving for the dream of a perfect son, while I said goodbye to the relationship we once had. He had come from a village where being gay was

non-existent. In four months’ time, I was in a deep depression. I wasn’t eating or sleeping – something had taken everything I was away. He blamed my homosexuality. I was far from happy; instead, I was close to death. I wished for him to say, “I love you, I understand” as if it was natural. But in Chinese culture it’s not something we do; “mental illnesses” aren’t a thing. We must be strong.

Months passed and I travelled to Hong Kong, desperate for answers. I finally realised I had suppressed the reality that my mother was gone. I would pray at her grave: “Come back, make me better, make it go away.” But I eventually accepted she wasn’t there; she had left me. So, I let go of her and I healed.

Today, things are different. My father doesn’t really talk about it, nor does he mention anything about my partner. Yet, like many Chinese fathers, he shows his love and acceptance through different gestures. He is a man full of love, but like so many fathers, he simply doesn’t know how to express it. He has feelings, yet not the words. Slowly I’ve realised he’s still proud of me. He still collects the magazines I’m published in, so perhaps reading this, he’ll understand even more that this is who I am. And although I have struggled and been through a lot of obstacles, I am not alone. And Dad, I am truly happy.

A Red Wedding Banquet – Kenneth’s Story

This image displays my father’s idea and dream of a Chinese wedding banquet destroyed by the presence of my homosexuality. There is a teapot and a cup representing the traditional tea ceremony of a wedding and the two fish representing the unity of marriage. Yet, there is also a condom there to show the presence of male sexual culture and broken lychees and eggs to show how my homosexuality has destroyed the promise of fertility.

Mel

Mel, age 25

Please introduce yourself.

My name is Mel. I grew up in Ealing, London and my parents grew up in Hong Kong.

What was your childhood like in relation to your sexuality?

It wasn’t really spoken about. I never had the sex talk. I guess it was presumed me and my brother were straight.

Why do you think in Chinese culture that we don’t talk about these things?

I think it’s almost a fear or an embarrassment – as if they talk about being gay, their child will think it’s okay to be gay or they’ll turn gay.

How do you identify today?

I identify as non-binary transmasculine. I used to have long hair to appear more femme, because I felt misunderstood. But I realised that growing out my hair was me just trying to cover up who I wanted to be.

And what do you think about that in relation to Chinese culture?

I feel like in Chinese culture, there’s only one box – you’re straight. And if you’re anything else, it’s like, “What did your parents do to you?” And it kind of falls down to your parents. My mum once said, “What did we do to make you do this?”

Speaking of your parents, can you tell me your coming-out story?

Well, I was actually outed. My mum and I would have big arguments about it. I remember me shaving my head and that appearing more masculine meant I would be “gayer”. So every time I would cut my hair, my mum would get so mad.

Why do you think your mum had such a strong reaction about your hair?

Because my mum never spoke to me about it. She always spoke to my brother, but she never went to me, so she exploded. She had been repressing all these feelings. In Chinese culture, I feel like we don’t really speak about things.

Why do you think that is?

I think it’s generation trauma – we don’t talk about things that are outside the norm. I think it’s our responsibility as queer people to change that story and erase the trauma, so our children and future generations don’t have to suffer like that.

What happened when you came out?

I was dating this girl and we broke up. Her mum had found these letters and birthday cards that had romantic content in them; she told me her father hit her when he found out. Her mum decided to go into my dad’s restaurant and tell him. My mum asked me, “Why are you messing around with this girl?” I replied, “I’m not straight.” She just cried and left my room. After that, everything in the house felt tense.

Why do you think she had such a strong reaction?

I think there’s a massive pride element. “How do I tell my sisters and our aunties you’re gay?” I think that’s a problem, because in our community, I think it’s very much to do with pride. They want to show off their children, but my mum was embarrassed to say her child was gay.

Did you ever feel embarrassed?

I used to feel like that. I’ve been out for eight years, and for the first three to four years, I was embarrassed. Now I feel like I’m coming into my own by finding a community with other queer East Asians. I feel like I did nothing wrong. I trained myself constantly, telling myself, “I’m not a failure. I did not fail my parents.” And it’s sad, as your parents should tell you that. But now at the age of 25, it’s quite nice to hear that my parents are proud of me and love me.

The Rice Bowl – Mel’s Story

Mel was outed by her ex-girlfriend’s parents. The smashed rice bowl shows the sadness and shock of being outed. The cut hair surrounding the bowl represents Mel shaving her head, finally getting to see who they were. However, the fortune cookie is there to show there is optimism and fortune that can arise from coming out.

Jay

Jay, age 29

Please introduce yourself.

Hi, my name is Jay. I’m 29 and I’m from Taiwan,

Was it difficult to come out?

Before I realised I was gay, I thought I was normal. We would make fun of the feminine gay guys. And then I realised I was actually one of them – I was gay.

How did you feel?

I was scared, angry and frustrated.

Why do you think parents don’t react well to their children coming out?

I think it’s a misunderstanding. I think being gay has been tied to negative connotations, with things like AIDS. People don’t like things they don’t know anything about.

Can you tell me about when you came out?

I remember taking a gap year in America and thinking I wanted my parents to be part of my life. I also didn’t want to join the army. I decided to write a coming-out letter. I read it out to them – I remember I asked them to sit down with me. At the beginning of the letter, I was fine, until it got to the moment I had to tell them I was gay. I was crying and reading at the same time. I tried my best to keep reading, but I couldn’t. I was so scared to see their reactions. But my mum just said, “I love you.” It took a while for them to digest it – for half a year, we didn’t really talk about it. We still don’t, but now everything feels normal.

Do you wish your parents would talk about it more?

We come from a culture where we don’t really say “I love you” a lot or talk about things.

Do you wish they’d tell you they love you more often?

No, because I feel in Western culture, we say it all the time, so it loses its power. So when my parents said “I love you” after I came out, it meant everything to me – as I hadn’t really heard those words for years.

Can you tell me about the Taiwanese army and your coming out?

We must join the national [military] service when we come of age [from age 19]. However, in Taiwan, homosexuality is classified as a mental disability. Knowing that, it made me feel uncomfortable as a gay man, hearing, “You can’t do this because of your sexuality.” But by coming out, I didn’t have to join the army, so I didn’t have to be in an environment where perhaps I wouldn’t have been accepted.

The Crab – Jay’s Story

The crab in this image represents imperialism in Chinese culture. The imagery of the smashed plates and items below it represent the anger and force shown in the mentality and actions of the Taiwanese regime, who do not allow gay men and women to join the army due to homosexuality being seen as a mental disability. The letter beside the crab is a Coming Out letter and the mess and cut sleeves below show the problematic chaos that ensues from coming out in the army.

Fan

Fan, age 29

Please introduce yourself.

My name is Fan and I’m from Taiwan,

Can you tell me a little about your childhood?

I grew up in a very open family, so I realised I liked the same sex since kindergarten, but I just didn’t know who I was. I hid myself under the pressures of high-school studies.

Did you have any confusion about your identity or sexuality growing up?

I wouldn’t say confusion – I’ve met a few transgender people while growing up, and most of them hated their bodies since they were children, but for me I didn’t think like that. I just thought that I like to dress like that and I want to be considered as a girl. You should be free to be who you want.

Did you feel this freedom in Chinese culture?

No, not until I was in university – but it was still hard to find it. Many people were just pretending to be open-minded.

Why do you think there wasn’t this freedom available?

Because the Confucian traditions are very strong in the Chinese mentality – and it’s so hard to break the rules.

Did you feel like you broke the rules?

Yes, I did – and I liked it.

It sounds like you were fearless!

Yes! I got that confidence from my friends, but I don’t feel like I’m fearless. I still care what others think of me, which is from my parents. But it made me feel like I could reach what I wanted to be. It motivated me and I’m still on that journey. And I feel like it’s limitless, but I also wanted to be an influence to show others that we can get this freedom. I don’t want anyone to feel alone.

What is your story of coming out and transitioning?

After studying theatre, I went to join the national service. I was in the theatre arts, so I chose to be in the entertainment group – I wasn’t holding guns, I was performing. I had to dress up as various characters; I would dress up as Disney princesses. I was the only feminine guy in the group, so I would wear wigs, dresses and heels. And so many people told me, “You’re so beautiful!” After that, it hit me – I had the potential to become a girl. I think so many men don’t have that opportunity to dress up openly as a woman in public; they must hide and go into their mother’s closet in secret. So I was very lucky.

Did you ever feel like your past self was being left behind, or was it a smooth transition?

It was smooth, but there was a goodbye to the boy version of me. It was a difficult process. It’s only been four years, so the past 25 years was me being a boy – it feels like it was a different person or body.

If you could give advice to anyone questioning their identity, what would it be?

There should be no regrets. You should live in the moment when you’re happy. So choose what makes you happy.

Aaron

Aaron, age 55

Please introduce yourself.

My name is Aaron Yap. I’m 55 years old. My parents are from China and they immigrated to Malaysia in the ’40s.

Can you tell me about your childhood?

We were poor. We grew up in the suburbs in the ’60s and it never occurred to me about coming out. I thought I was the only gay person in town, so it was terribly confusing and scary.

Did you have any concept of what being gay was?

No, I went looking for answers. I looked up “homosexuality” in the encyclopaedia. It was unfortunate, because kids my age who were gay had no resources. I was hoping it was just a phase and that I’d come out the other side “normal”. I was isolated and wanted to get out of that tiny village.

What was your coming out like?

When I was 18, I joined the navy. Towards the end of the recruitment, I went to study in London and I still wasn’t out to my family. But I came out to my closest sister; it was unplanned, but it just happened. I told her. But she wasn’t equipped to be sympathetic towards me or say anything about it. She pushed everything aside and up to now, more than 30 years later, she still doesn’t acknowledge it. It’s as if I came out to the wrong sister. And I felt pushed back in the closet. It scared me that this could happen again. It wasn’t until seven years later, when I told my eldest niece. I was very close to her – she’s like a daughter to me. Although she’s 15 years younger than me, she has a completely different mentality towards homosexuality – she has had more exposure to it. When I came out to her, she just said, “We knew!” And I got closer to her and her family. I felt like I didn’t have to lie or live a double life. It was freedom.

How do you feel when you think about people of your generation who have such difficulty digesting what being gay is?

Well, I feel like people in our culture think of us like a tribe. And if we are not helping the tribe – such as not reproducing – we’re doing something wrong. With China, we closed ourselves off from the world for so many years and we still hold onto traditions, such as carrying on the childhood name.

Do you feel like people of your generation still have an opportunity to learn about homosexuality?

I think it’s so deep-rooted, like you’re brainwashed to the point where you think it’s not normal and it’s wrong. In the past, it was so much harder – there were punishments or “treatments” for being gay. But it’s getting easier. It’s your intention on what you want to do, which is important, and your choice on whether or not you find things to educate yourself.

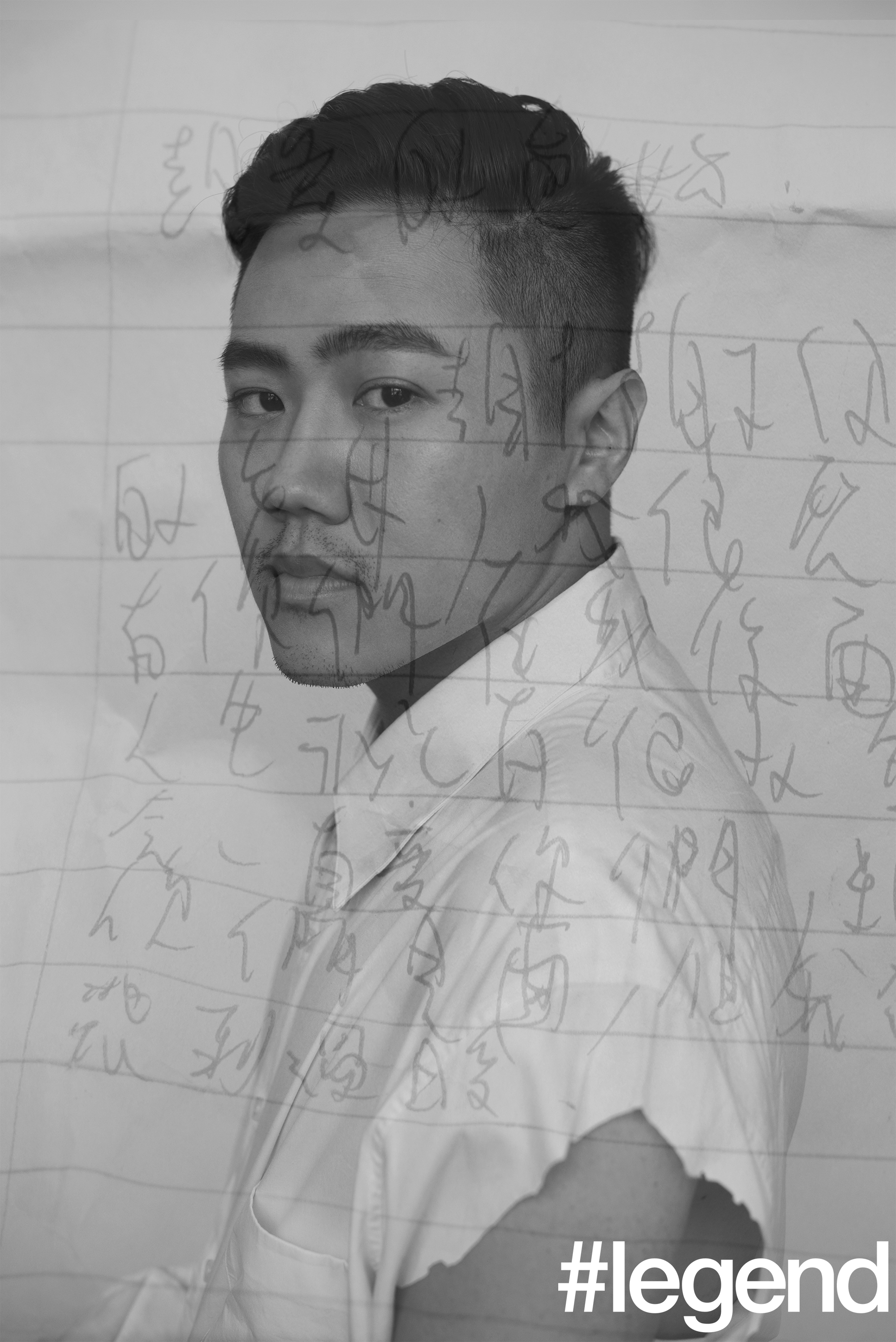

Alexander

Alexander, age 28

Please introduce yourself.

My dad was born in Guangzhou, China and my mother was born in Liverpool. I was born and bred in Manchester. I was given the title “the Golden Child” by my sister.

Did you ever feel a division between your Chinese side and your English side?

When I was born, I think my father’s side loved the fact that I looked so Chinese, while my British grandmother said, “You have a yellow baby.”

Growing up, did you feel like your identity was challenged because you were Chinese in Britain?

I remember when I was young, I just wanted to wake up and not have my Chinese eyes, and I didn’t want to be Chinese. I got bullied a lot – rocks would be thrown at me because I was Asian. I did have an identity issue. I had to get over it and I had to learn to love being Chinese. When I saw Chinese actors and actresses and models, I thought, “Wow, they’re so beautiful” and I began to appreciate my culture. That’s why representation is so important.

Can you tell me about your coming out to your parents?

I remember my parents were watching this film on the TV and every commercial break, I kept wanting to say it. And eventually when the film ended, I came out with it. My dad was very accepting at first and my mum wasn’t, because she was worried about the scrutiny and the grandchildren. But the next day, my father sobered up and things got difficult. Me coming out was an embarrassment – I am the first son of the first son, so I was supposed to carry on the name – so me being gay was a big thing. He even worried I was going to be killed because I was gay.

Do you feel that your father’s strong reaction was due to entrenched Chinese traditions?

Yes, because everything he was saying was so not English – it was a different reaction to my British side of the family. My dad would say things like, “This is not Chinese culture.”

Have things changed?

My father did become more understanding, which was done through private conversations with my mum. It got to a point where I was with my third boyfriend when I was 17; we ended up being together for four years and I was 21 and I broke up with him. And my dad said, “He was a nice guy! Why did he ruin it?” I realised my dad was trying to convince me to stay with a guy – and I felt like he was beginning to understand it.

Do you have any advice for any young boys who are questioning their sexuality or facing obstacles?

I don’t want to say just be you – I don’t think it’s fair to tell someone to just be confident and be yourself, because everyone has their own journey. It might not be the time to come out, but trust your journey, because for me it wasn’t an easy journey. It wasn’t good or easy, but it was perfect for me, because right now, I’m happy. If you don’t feel you’re there yet, don’t force yourself. It’ll naturally come.

Ky Ha

Ky Ha, age 39

Please introduce yourself.

My name is Ky Ha. I was born in Vietnam; my father’s Chinese and my mother’s Vietnamese.

What was childhood like for you?

There was a lot of pressure to excel in my studies and to make money to look after my parents when they got older.

Was there a sense of pride when you did achieve things?

Oh, for sure! I remember my parents would always brag about me. I remember theywere proud of my honours – they would show photos of me to their friends. At the same time, they would also brag about their children’s friends, saying this child has got married, had kids, et cetera.

Why do you think they would compare you to them?

It was a motivational tool, but it was also damaging at times. It affected my self-confidence and it gave me a fear of failing. I feel like in our culture, it’s like, “Don’t try unless you’re going to fully succeed or come out on top.”

Do you think things changed when you came out?

Yes, when friends ask my parents if I’m married, they say, “Oh, he has no wife yet.”

Can I ask about your story of coming out?

I didn’t tell my parents until I was 28. At that age, I kept being nagged about getting a wife. My mum was just nagging me so much that I just said, “It’s not going to happen – I’m gay.” She told my dad, and for a couple of years, they said, “It’s just a phase – you’ll find a wife.” I let them live out their emotions, as although I felt things, I knew they felt emotions, too; I had to remember it was a two-way street. I know they had hopes and dreams. But today I know they’re proud of me. They have photos of me doing my work and they talk about me to their friends. But it took time.

Marriage and Coversion Therapy

This image shows the struggle of homosexuality with marriage and conversion therapy. There will always be those praying the “gay away,” shown with the presence of the Buddhist mantras and the statue. The fruit represents what Chinese men will face if they stay closeted or married, with the pomegranates, dates and lychees represent the fertility that can come from hiding their true self. If they do not conceal their sexuality they are faced with the idea of conversion hospitals. The cut sleeve that divides the objects with a smashed plate, pills and needles represents the horrors that gay people face in conversion hospitals, with the wire represents electrotherapy.

Photography & Text / Kenneth Lam