#culture / #art & design

Pioneer Dealer Steve Lazarides on Banksy and the Mainstreaming of Street Art

April 1, 2016

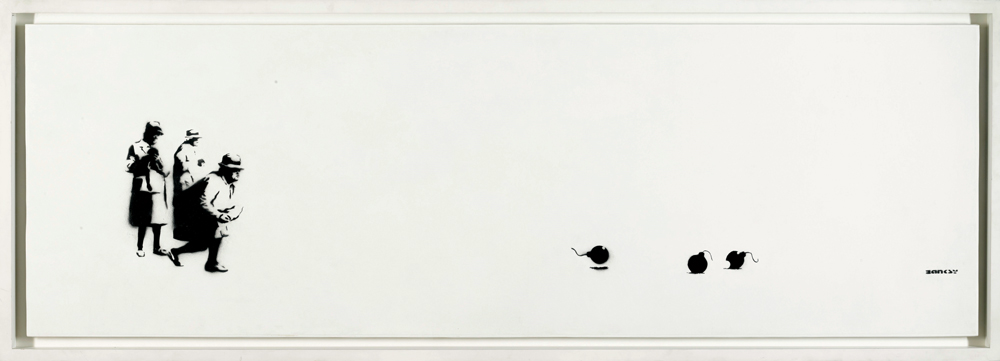

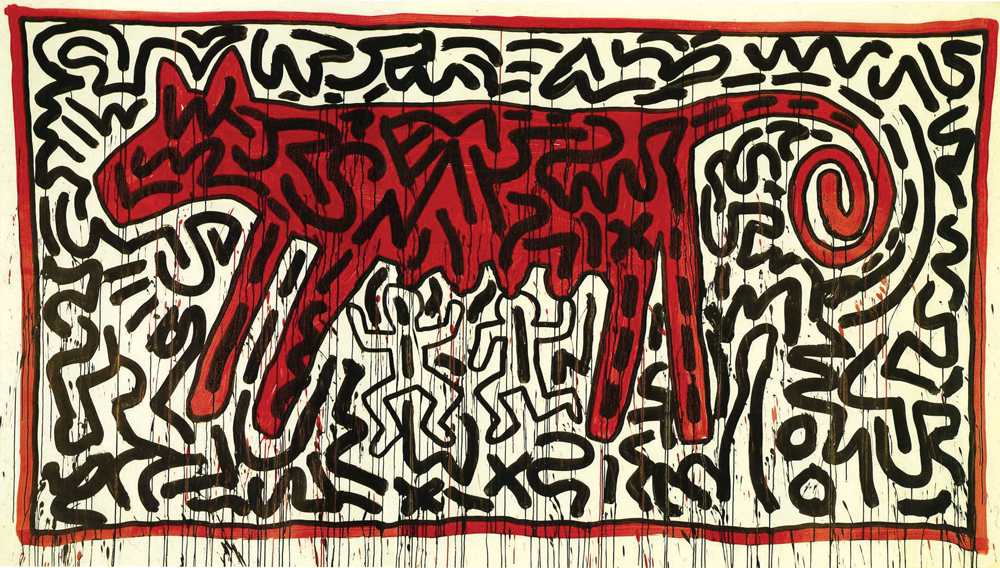

Street art has evolved from an underground movement rooted in graffiti and hip-hop to a highly regarded genre on the global art stage. Witness, They Would Be Kings, Sotheby’s first street art exhibition in Asia, which charts the trends and progression of street art, from the pioneering works of Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring to today’s contemporary legends like Banksy and JR.

One man who has done more than any to highlight the allure of such work is Bristol-born art dealer and curator Steve Lazarides, who at the age of 37, launched his first London gallery in 2006 and began showing work inspired by graffiti and the urban environment, most famously of street painter Banksy, whom he’s credited with discovering and managing until 2008, when they “split.”

Lazarides has since expanded, generating an interest in street art off which others have capitalised. There were epic shows too, Hell’s Half Acre (2010), The Minotaur (2011) and Bedlam (2012), exhibitions which ran over Frieze week in The Old Vic Tunnels with Kevin Spacey were a huge success and met with critical acclaim. In 2013, Lazarides teamed up with The Vinyl Factory to present Brutal at 180 The Strand during Frieze London. Last year, he curated Banksy: The Unauthorised Retrospective at Sotheby’s S|2 Gallery, displaying never before seen works from his own collection.

But right now, two weeks before his Hong Kong exhibition with Sotheby’s by phone from London, he’s questioning the title for the show. “It’s called They Would Be Kings but perhaps it ought to be called They Should Be Kings.” He goes on to explain how he has met Jean-Michel Basquiat, Dominic White, JR, Banksy, describing them as “guys who have followings that run into millions around the world, and far, far more so than a lot of contemporary art and artists.”

The “king” reference is endemic to the early days of the street art movement and many of its artists have embraced the term. Basquiat famously references the king and crown emblems as a signature of his work. The title also acknowledges the “king-makers”, or taste-making gallerists that have supported the street art empire over the years.

Including Lazarides. “It’s not just the street art, it’s a whole movement of people I’ve worked with, a collective of individuals with a very common kind of theme and goal. They were given a massive sense of freedom and a certain level of irreverence. These guys forged their own path; they bludgeoned their way into the public consciousness, and then were finally noticed by the art world.”

There’s a touch of Malcolm McLaren about Lazarides, like he’s the street art impresario of the wrecks, the wastrels, the underground urchins and the poet noctambulists who were post-punk. They turned and tagged their disenchantment on the aesthetic of inner city walls and subway trains, their words like ephemeral, savage flowers of dark art blooming everywhere in the slums and shadows, the shared but unspoken language of tribal hieroglyph. But try telling Lazarides he’s the king of street art representation. “People think I like street art. In truth, I hate 98 per cent of it and think it’s terrible. But, I do like innovators.”

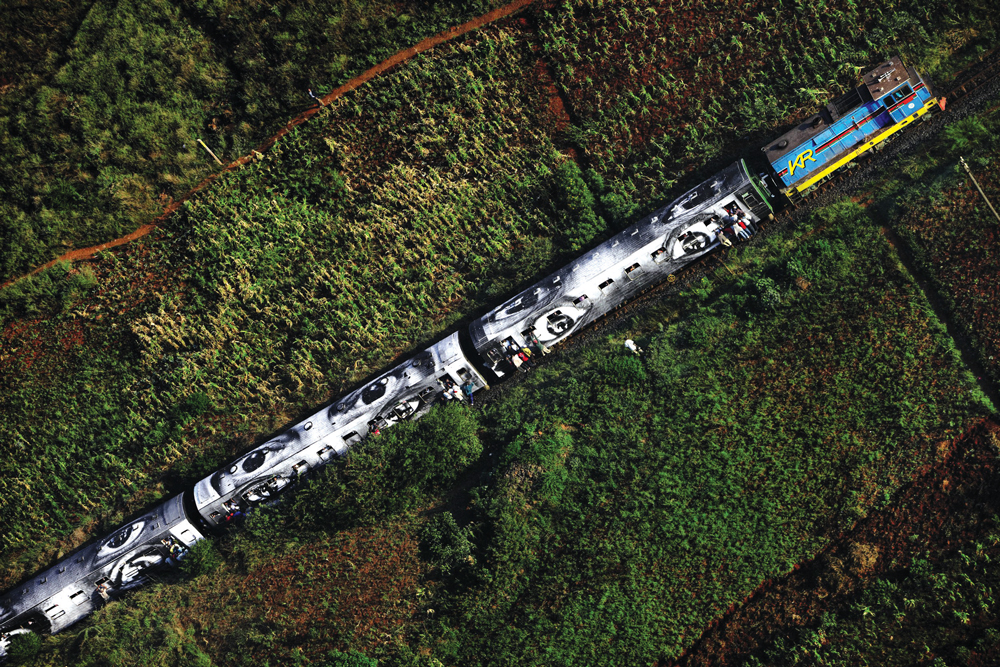

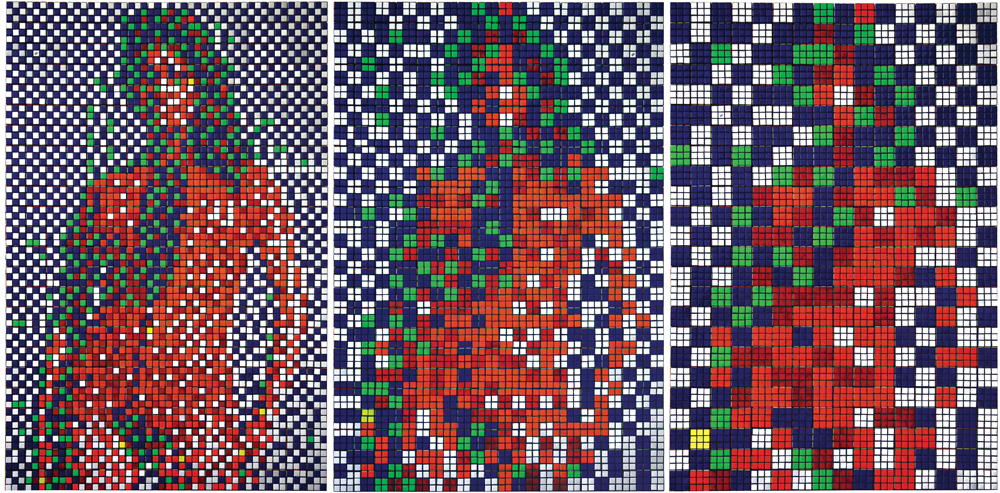

He lists the art innovators he’s made famous: Banksy and stencils, JR and massive photos, Vhils chopping things out of the streets, Invader taking to the shadows with a tiling kit. “These guys were so left-field they created a tribe of their own. To call them ‘street artists’ is…well, it’s not quite disrespectful but I still haven’t worked out what they should be called. No wait, I have worked out what they should be called. They should just be called artists along with everyone else.”

Of course the whole aesthetic has been ghetto-ised, which Lazarides blames on the hierarchical, ivory-towered art ecosystem. “The traditional art world did everything they could, really, to try and bury it and as a result it just became stronger and stronger.”

A metaphor for Lazarides’ career. He never intended to be a gallery owner, claiming he had little idea what his professional trajectory would be after leaving Newcastle University with a photography degree. “I thought I’d end up assisting [David] Bailey for a while and then I jacked it all in. Funnily enough he became a client of mine 10 years later. He bought a Banksy off us.”

Meantime, Lazarides worked as a painter, decorator and van driver – “the lowest paid person I knew within my peer group” – until his early 30s at which juncture his wife bought a copy of Sleazenation magazine with graffiti on the cover. “That was the one love of my life. So I went to the magazine, did two weeks, and came up with the idea of starting a photo agency specialising in British youth culture.” He was also told to shoot an obscure and anonymous local painter called Banksy. He did, and Banksy never stopped ringing Lazarides thereafter. “I just wanted to do what I liked and what I was interested in.”

And how. Lazarides this year celebrates a decade in the business, his thoughts as much futuristic as retrospective, given recent investment he’s secured from Qatari businessman Wissam Al Mana, who also happens to be Janet Jackson’s husband. The new partnership with Al Mana opens up a wealth of possibilities for a gallery that has never lacked zeal or vigour. “I’m damn proud of it, too,” says Lazarides. “We may be an odd couple but we approach art from the same perspective and have a common goal for the future of the gallery.”

Qatari born Al Mana, 41, is a prolific art collector who was raised and educated in London and worked in fashion and design jobs before embarking on his eponymous conglomerate operating activities ranging from real estate to retail.

Don’t expect Lazarides to desert the streets though, he’s merely upscaling postcodes to London’s Mayfair, ordinarily the enclave of A-list art dealers Lazarides appears to denounce. “Firstly, no-one can ever pronounce my name so we’re changing it to LazInc. Secondly, we’re moving to Mayfair. We’ve spent years working from a position of isolation, and now it’s time to challenge the status quo from the inside. I can hear the shouts of ‘sell-out’ on the Internet from here. But find out what we have planned before you dish out any hate,” says Lazarides.

“There have been a huge number of artists, collectors and well-wishers from across the social spectrum who have made this gallery possible,” he says. One of whom is Damien Hirst. “I put the phone down on him five times,” he says. “A guy kept phoning saying, ‘I’m Damien Hirst’ and I said, ‘Yeah, pull the other one’.” Hirst did finally get connected and became both friend and collector.

“A lot of people have had a lot to say about Damien but the man cannot do anything wrong. He is Robin Hood. He used money that he made, buying from people like us, and other young artists, things that no-one ever talks about. He looked after his staff amazingly well. Yet he gets so much shit for what he’s done when, in fact, he’s done so much good. He used that to inspire, help, fund and give advice to lots of other young artists which I think is a brilliant thing.”

Lazarides credits Hirst with bringing collectors from other galleries and pushing his name out to an art world that knew little of him, but still, “there’s always a bunch of people who either suck up to Hirst, or slag him off. There’s nothing he can do to win. That’s Great Britain for you,” says LazInc.

So what of Hong Kong? “I view the city the same way I view Istanbul: a gateway to another culture. That you come and you’re almost reaching out to China. And the other thing is, and I don’t know what trouble artists get into or not, but the regime there must be fairly receptive to street art otherwise these guys wouldn’t keep coming. My knowledge of the Hong Kong and Chinese art market is appalling. But, in my defence, my knowledge of the art world everywhere else in the world, is also appalling, including England.”

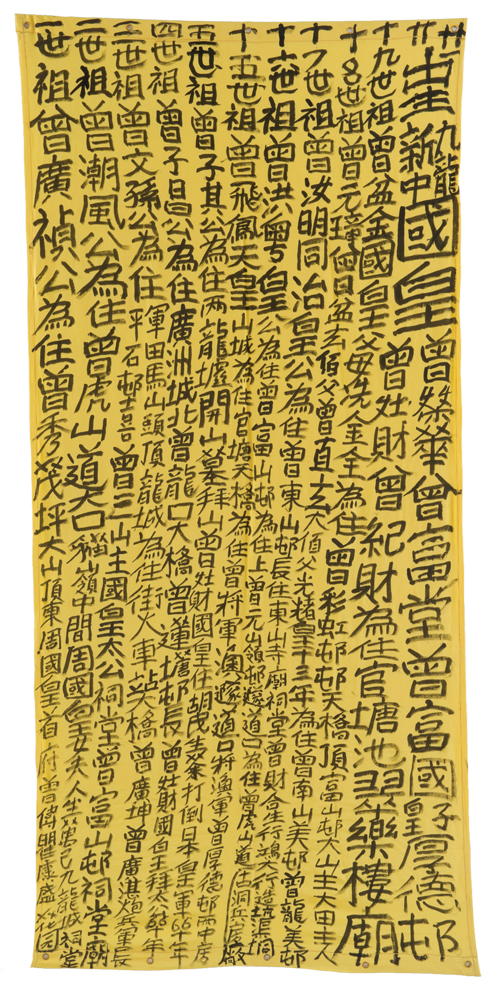

How then has he chosen Tsang Tsou Choi, the King of Kowloon, for his show? “I tell you what, I don’t know a great deal about it but when I came last time, about five years ago, there was an exhibition of his work on and I managed, just before I was leaving, to get a kind of two-minute run in the door, run around and run back out again, and I really liked it. And from the point of view of stylistic value, I quite liked the vibe of it.”

The same way he likes the vibe of China and Russia. “If you look at both China and Russia, they’re steeped in very creative history, but you can’t suppress that depth forever, so it’s very much due a kind of explosion at some point soon. China and Russia are of course very different, but I am a great collector of communist art and the aesthetic. And you know, that aesthetic has more influence on people like Banksy and Shepard Fairey, than graffiti. From my perspective, I think Russia will go massive at some point, from what I’ve seen of the underground.”

Outside of street art, Lazarides has other artistic passions. “Pieter Hugo, photographer. I’ve got a couple of pieces of his. I very much like Keith Tyson. “It’s not all super hardcore, really dark, or overtly political, there’s a glimmer of a theme perhaps that runs through what I like. But at the end of the day, you see something and think, that’s a great piece of art.

“That’s been my argument about the whole of the art world. There is really not a power on earth that can convince someone that something is good if they think it’s bad. And I’ve found this from the beginning. So my advice to people is buy it if you like it. And of course it really doesn’t matter then if it goes up or down in value, of course no one wants to buy something and lose lots of money on it, but if you buy it because you like it you’ve got a lifetime’s enjoyment to take out of it.”

What of his collector base? “We have a very, very diverse client base from across the world, and sometimes it’s very hard to work out who the end buyer is,” he says.

“Someone told me a great story about Lionel Richie the other day, that he has loads of my art in his house. Well, I’ve never sold anything to Lionel Richie. The answer was, he’d been buying it through a gallery in Amsterdam because he likes the name; it’s called the Richie gallery.”

Does Lazarides also have a base of Chinese street art collectors? “There is a guy in Hong Kong, who is a massive collector of street art and there’s a couple of other people. Outside of that, I don’t really know. I’m not going to pretend I’ve got 20 Chinese private clients because I haven’t. And to be honest, even if I did I wouldn’t tell you…how’s that for brutal honesty?”

Some in the art world, conspiracy theorists you might even call them, harbour a belief that Lazarides has invented Banksy as an artistic alter ego extraordinaire, and that Lazarides may even be the elusive Banksy. It’s “brutal honesty moment” in return. Can he share an email for Banksy so this writer might enquire what the artist has to say about his supremo manager Steve Lazarides. “We haven’t spoken in eight years,” Lazarides says, quickly shutting down an electronic avenue to “meet” the most famous artist on the planet.

“What do you say to people who say Steve Lazarides is Banksy? That Absinthe was banned for a bloody good reason.” Touché.

“Really, all I’ve ever done, is just put a bunch of artists whose disparate work I really like in a gallery and said, ‘Here’s what I like’. I’m not trying to convince people that my choice of things is better than anyone else’s because it’s not. It’s all personal taste.”