#culture / #art & design

Artist Tsang Kin Wah Balances Global Acclaim With Hong Kong Anonymity

BY #legend

November 1, 2016

Who’s your favourite Hong Kong artist? An easy question given the onslaught of art that’s made its way to the city in recent years. There’s an agony of choice: Art Basel in Hong Kong will stage its fifth iteration next year; the much lauded and lambasted M+ Museum, currently the biggest museum under construction anywhere in the world, opens in 2019; and Rachel Lehmann, pioneering co-founder of New York-based Lehmann Maupin is planning an exhibition of contemporary Hong Kong art and artists at one of her two spaces in Manhattan next year.

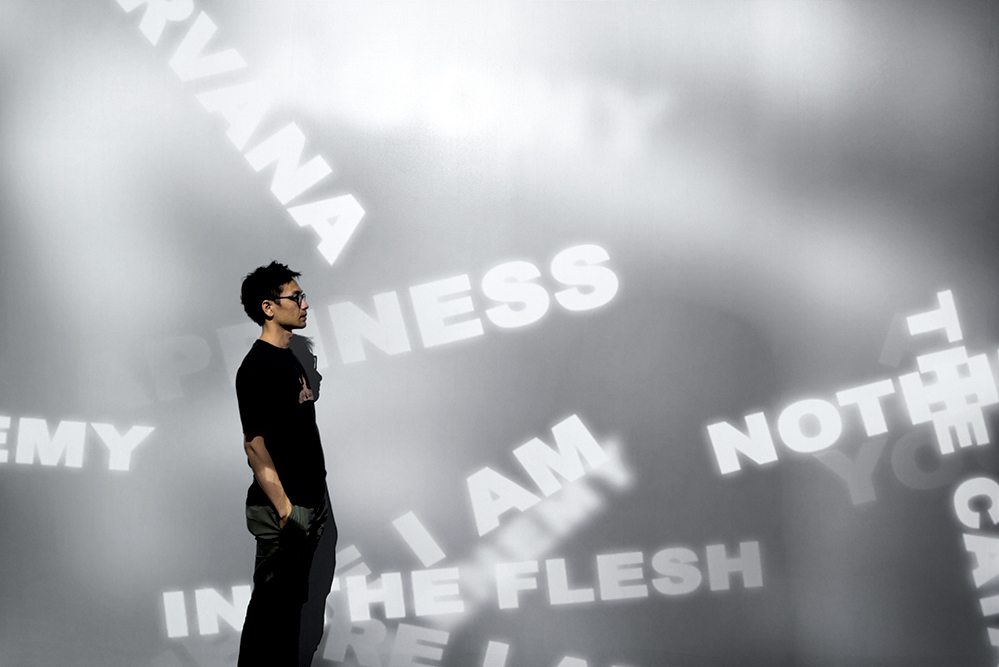

These groundbreaking moves suggest Hong Kong may be on the cusp of its first major global art moment. This must make for heady times for Hong Kong artist Tsang Kin Wah, who continues to blaze a trail on the international stage. While he represented Hong Kong at last year’s Venice Biennale and his work is collected by leading global museums, his name stirs little recognition here.

I’m curious to know more of his underknown-ness when I meet Tsang at M+ Pavilion in Tsim Sha Tsui, where his latest exhibition, Tsang Kin Wah: Nothing, has been showing. He is about to head off to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York for exhibition. “I’m not very active in Hong Kong and I stay away from shows and openings. It’s not like that’s become a habit and I don’t want it to be one,” says Tsang. “Most of the time I stay at home or my studio. I also don’t do a lot of interviews. I think it’s hard for people, even in the art circle, to know more.”

The co-curator of the Nothing exhibition and the M+ lead curator for learning and interpretation, Stella Fong – who is also a long-time friend of Tsang’s – agrees. “He keeps an extremely low profile,” she says. “I think a lot of people, even in the art world, treat him as a mysterious figure. He should have more here but there are not many opportunities in Hong Kong to see his work.” All of this is somewhat ironic. If Tsang were a luxury brand, his discretion and stealth would be exactly the qualities that purveyors of upscale lifestyle retail are desperately trying to re-establish after years of zealous overexpansion. He would be more covetable than a Hermès Birkin.

Fong says Tsang’s tendency to say “no” more often than he says “yes” has cultivated a kind of renown. “I know he turns down some of the offers that he gets. That makes him interesting in its own right,” she says.

At what should have been his crowning moment at last year’s Biennale, Tsang felt more the twinge of regret than burgeoning global or local, renown. “I enjoyed the installation and the opening itself but the other days didn’t attract me a lot. It was just big parties for big galleries with people from around the world,” he says.

Appearance and reality in both art and life merged. “Even though we put in a lot of effort, I feel in the final outcome, it just ended up as something different. And that made me feel there was something wrong.” Tsang switched to default mode, which for him, means reading Nietzsche. He’s revisited the philosopher’s On the Genealogy of Morality three times in the past three years. “On previous readings I had found Nietzsche very optimistic about embracing lives and, at that time, I thought I could make myself better, a better man. After looking at more of the world and Hong Kong, I realise that it is just an illusion and there is no way for us to become a better man. I shifted to a more pessimistic view.”

The current exhibition is a harbinger of two important milestones in Hong Kong. It will inaugurate the M+ Pavilion, the first permanent structure to be completed at the West Kowloon Cultural District and the home of the M+ exhibition programme until 2019, when the main building opens. It’s also a continuation of the exhibition that follows Tsang’s acclaimed work The Infinite Nothing.

In both exhibitions, viewers find themselves immersed in a constellation of images and ideas, amid a bewildering array of sources and references that run from Shakespeare’s Macbeth, to Kurt Cobain and Nietzsche, to Stanley Kubrick.

Fong says Tsang is always pushing himself. “He has two or three different personalities. He’s questioning himself all the time.” But Tsang’s more a kinetic Hamlet than a dark Macbeth; he has never stopped seeking identity and meaning. Born in Shantou, Guangdong, he migrated to Hong Kong at the age of six. After time spent in Britain and his subsequent return to Hong Kong, Tsang has considered questions of identity and existence, especially the interplay between appearance and truth. His work is acclaimed for its use of text and language, which he manipulates with computer technology to create immersive installations.

To wit, this month finds Tsang showing at the Guggenheim on New York’s Fifth Avenue as the only Hong Kong resident included in Tales of Our Time, an exhibition of Greater Chinese artists. Tsang’s work is an immersive projection of rocks, ships, oceans and waves washing over the viewer. In The End is The Word, the six-channel video installation interweaves found footage, sound and light at the site of the territorial dispute between the mainland and Japan, the Diaoyu Islands.

“I’m using a Chinese quotation and manipulating the text, which becomes a relationship between audience and work, an immersive experience related to China and Japan, in the style of animation. There will be some texts in various parts of the museum, and some ambient sounds.” The texts Tsang refers to form part of No(thing /Fact) Outside, a vinyl text installation that extends beyond the Guggenheim’s galleries, climbing walls and snaking along floors.

If this dramatic approach to his art continues in the striking vein he’s already set, Tsang may yet become everyone’s favourite.