#art & design

Hong Kong Godfather of designer toys and the making of his “artoys”

BY Yana Fung

March 1, 2022

Pioneer, trendsetter, designer, artist – there are many ways to describe Michael Lau. The Hongkonger best known as the Godfather of Designer Toys talks to Yana Fung about his 2021 exhibition and how he turns toys into art

Thanks to Al Pacino, any mention of the “Godfather” almost immediately invokes images of serious men in dapper suits who threaten to have you killed. Fortunately, this word association doesn’t apply to Michael Lau. The man

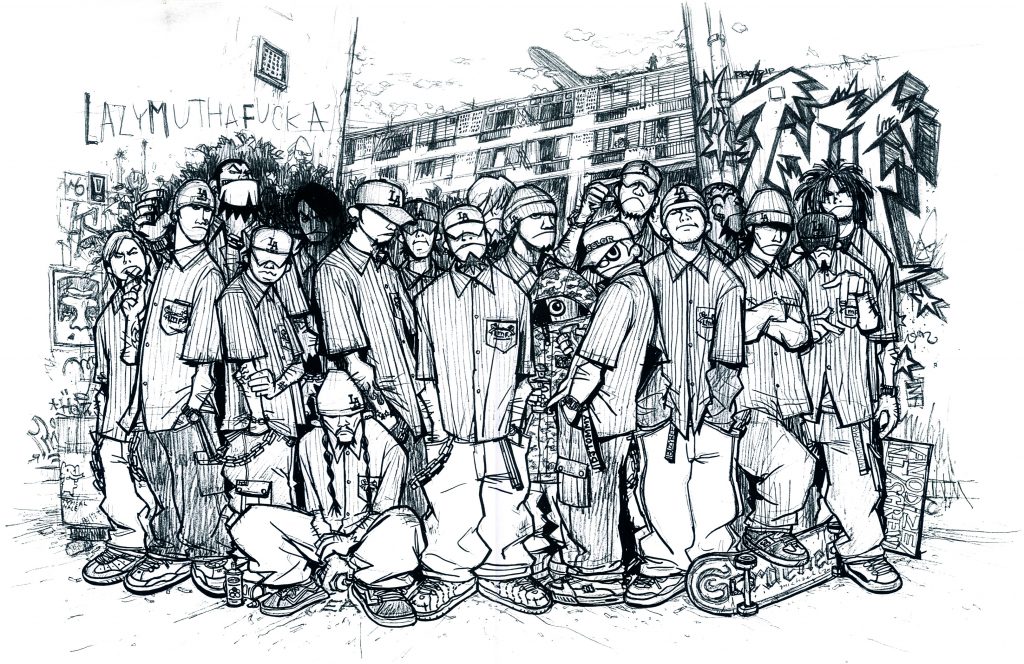

known as the Godfather of Designer Toys earned his title by showcasing 99 original action figures, something that had never been done before on such a large scale, in his landmark exhibition Gardener in 1999.

Still in his 20s, Lau found the moniker akin to wearing shoes that were too big to fill. “It was really weird because I was a young man but I was called a godfather. It should’ve been godkid or godson or something like that,” Lau says, laughing.

More than two decades later, however, and it’s obvious he’s grown into the title without thinking too much about the weight of such an acknowledgement. “Now I can take on the title of godfather and there’s no problem. It’s just a name. I’ve never been too bothered by it. I think it’s a sign of respect.”

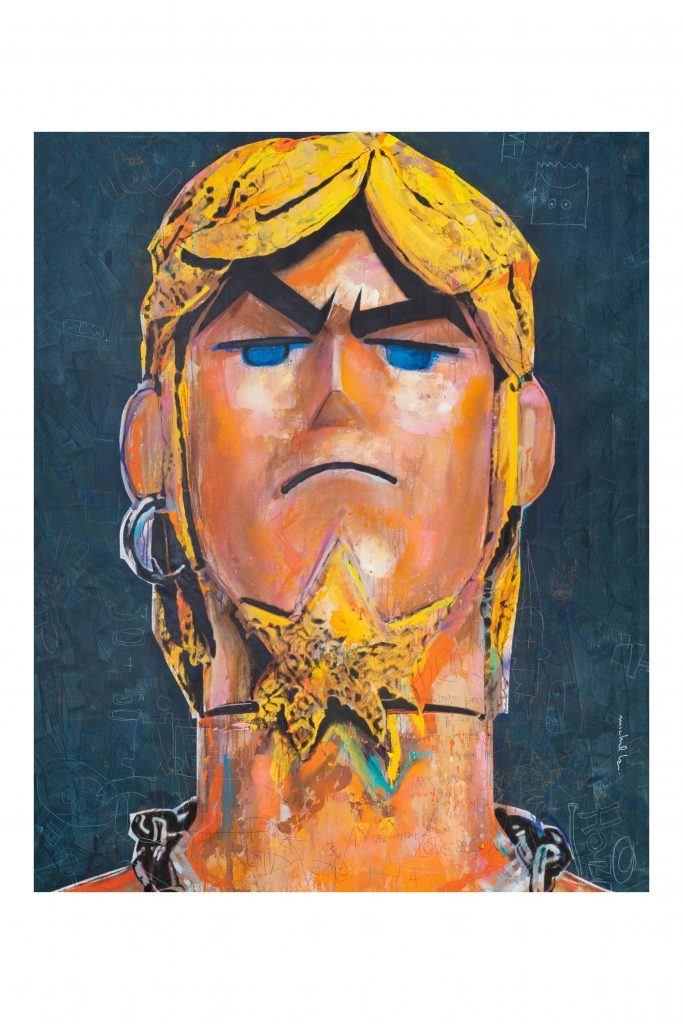

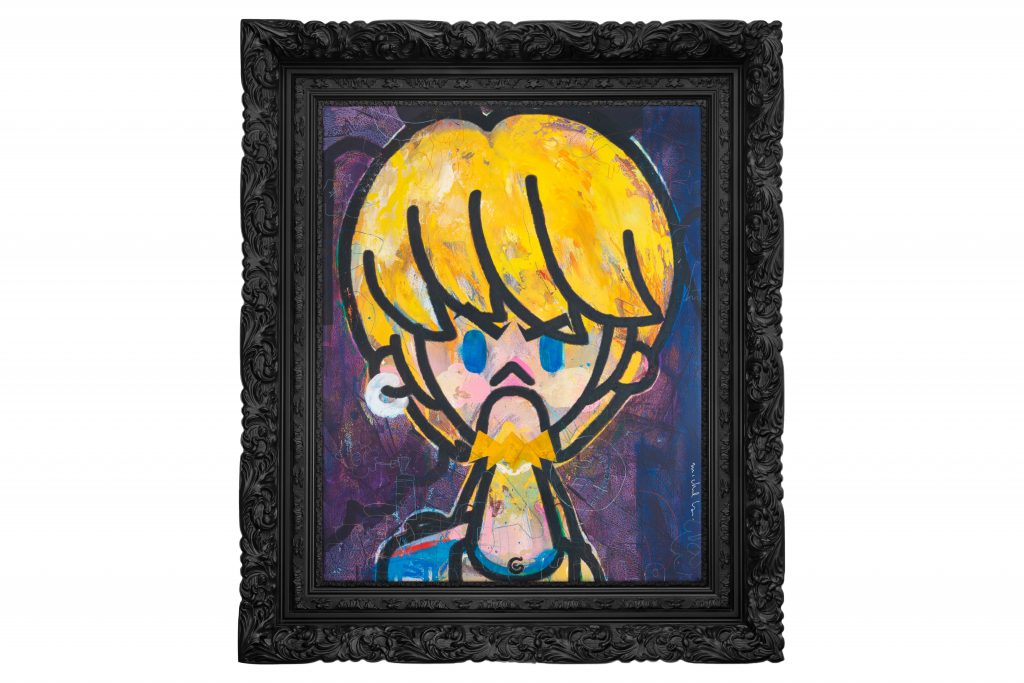

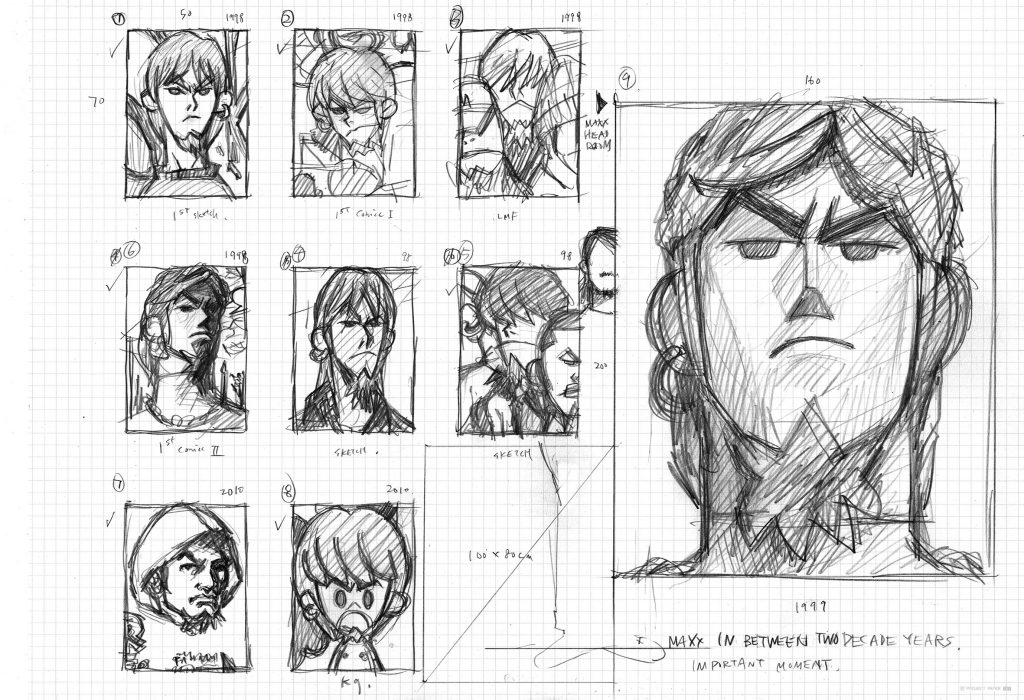

In a show of that respect, Woaw Gallery has offered up a tribute to the collection that started it all for Lau. Titled Maxx Headroom, the exhibition took a trip down the Gardener memory lane and revisits its origins, along with key moments chosen by Lau himself. “Every piece has a story. For this exhibition, I specifically chose moments from Gardener’s history over the course of 10 years,” Lau explains.

In a move away from previous iterations of Gardener, the exhibition focused on Maxx, the main character of the Gardener series and the character Lau considers his self-reflection. The collection chronicles Maxx’s journey and Lau’s along with it – from humble beginnings on the first Gardener logo to album covers and comics to the culmination of Gardener’s success in Lau’s eyes, an exhibition in one of the busiest malls in Hong Kong.

Also see: Tom Friedman’s interpretation of art as a break from hyperspeed lifestyles

With the ever-evolving nature of art and the seemingly natural way toys have integrated themselves into the art world, it’s difficult to imagine the ripple effect that Lau’s original Gardener exhibition caused. But the 99 figures he created essentially broke the mould and created a whole new category that combined fashion, art, toys and street culture.

“At the time I never thought it would be that extreme. I just wanted to do it, so it was very pure. I didn’t think too much about how great it would be. I just really wanted to do it,” says Lau, recalling the moments before his career and life changed. “The night after the opening, it felt like I had suddenly been transported to another world and this world had this thing called artoys and there was another Michael Lau, another person.”

Artoys, as the name suggests, are a cross between art and toys. While it sounds like an oxymoron, artoys prove that toys can be much more than mass-produced objects that are ultimately tossed aside for something newer and better. They can – and, according to Lau, should be – be valued and appreciated as art objects and quality goods.

“From a young age, I’ve always liked toys. Maybe it’s because I couldn’t afford to buy toys during my childhood. So once I was grown up and had my own money, I bought a lot of toys,” he explains.

The catalyst for the Gardener collection came in the form of a GI Joe action figure and the worldwide explosion of street culture, once again an unlikely pairing. Lau was caught in the middle of it all. “In 1999, I had my third exhibition and I wondered if there was a way to combine the toys I liked, the street culture I liked and the art I liked together to make a new art form to exhibit in an art venue.”

Out of nothing but his imagination and a desire to challenge himself, Lau launched a movement, changing the perception of toys from something cheap and commercial to limited-edition quality goods. Lau’s artoys went on to inspire other contemporary artists to experiment in their work. His influence is even said to reach as far as Kaws and Takashi Murakami.

Still, putting away your toys for good remains a rite of passage for many on the road to adulthood and toys that aren’t pricey watches or supercars are rare finds on any adult’s wish list. Lau sees things differently. “We’re young at heart. In our minds, we’re still little,” he says. Rather than being thrust into the cruel world of adulting all on your own, Lau’s figurines offer comfort and companionship to ease the transition from one life chapter to the next. “We don’t grow up, just our body does. But our mind stays like a child’s, very naughty. So why can something like toys still continue to appear? Because they’re not just for kids, they’re also for someone who is a child at heart.”

“It felt like I had suddenly been transported to another world and this world had this thing called artoys and there was another Michael Lau, another person” – Michael Lau

In a twist of fate, everything seemed to fall into place for Lau last year. Not only was skateboarding added to the Olympics, as a hallmark of street culture, but Lau also realised his long-term dream of showcasing his work at Art Basel Hong Kong. “I had previously gotten to know the Lévy Gorvy art gallery. Their boss in Hong Kong had worked together with me at Christie’s before and I had done an exhibition at Christie’s,” he explains. “It was surprising [when they invited me to join them at Art Basel] and it came about really suddenly. I was really delighted that this year I could tell people loudly and properly that I’m an artist.”

Reflected in Maxx is a similar story, that of a low-level, paste-up artist who dreamed to become a real artist. “[Last] year, it felt like I was able to achieve that dream and coincidentally I was able to do [the] exhibition, using Maxx to tell my story all over again,” Lau says. “All works are self-reflections of the artist. Even beyond Gardener, any paintings, you’ll always see the creator’s self-reflection. It’s always the creator’s work and their baby that they’ve given life to.”

The same is true for Maxx, who was born into similar circumstances as Lau. “We were relatively poor and we didn’t study, our English was bad. We didn’t study abroad, we were really local, so we were a really local group of young people. So it’s easy to project onto this character the things I couldn’t do, I could help him achieve.”

Of course, something that every artist must be asked is which of their work is their favourite. Much like a parent

being forced to choose a favourite child, Lau initially maintains that there are too many that he loves.

After some internal debate, a favourite emerges. “I think Gardener, because it was the best thing at the best time,” he says. The exhibition stands as the product of a simpler time, before “things got more complicated” as he grew up, Lau remarks. Going into more detail, he names Tattoo, another character from the Gardener series, as a favourite. As the first of the 99 figurines to be created and realised in a physical form, it has become the harbinger of Lau’s success. “The night [I created Tattoo] I felt like I had invented something by myself, something fun and very new, like I invented something that I knew would bring me to greatness.”

Also see: The family legacy of furniture designer Benjamin Paulin