Before quiet luxury, there was Delvaux

May 18, 2023

Belgian leather goods house Delvaux has been crafting handbags for two centuries, whether the trend be maximalism or minimalism. Zaneta Cheng visits the maison’s atelier in Brussels to find out how the brand continues to thrive

Quiet luxury is this season’s loudest trend. The new fashion phrase is permeating public consciousness thanks to various factors such as Gen Z TikTok-ers and Reel makers who have been exploring tropes like the “old-money girl” and delving into Princess Diana’s off-duty wardrobe; general hysteria around the wardrobe in Succession, a hit tragicomedy on HBO about a billionaire media mogul’s family empire; and most recently, Gwyneth Paltrow’s wardrobe during her ski-accident trial.

Perhaps it’s late-stage capitalism. Perhaps we’re all just tired of logos emblazoned on clothing rendering fashion houses purveyors of branded merch rather than bastions of taste and craftsmanship. Whichever way one looks at it, quiet luxury is sticking around.

But what is it, really? Not quite normcore of the early 2010s, quiet luxury is new-age minimalism. Its philosophy has grown out of the increasing awareness to buy mindfully – investing in quality pieces that will last rather than indulging in pieces for one season only.

But this begs another question. What is luxury these days? Does real quality still exist when brands are having 80% if not more of their goods made in cheaper factories anywhere around the world only to have items labelled “made in Italy” or “made in France” when workers in these two countries work on minimal finishings?

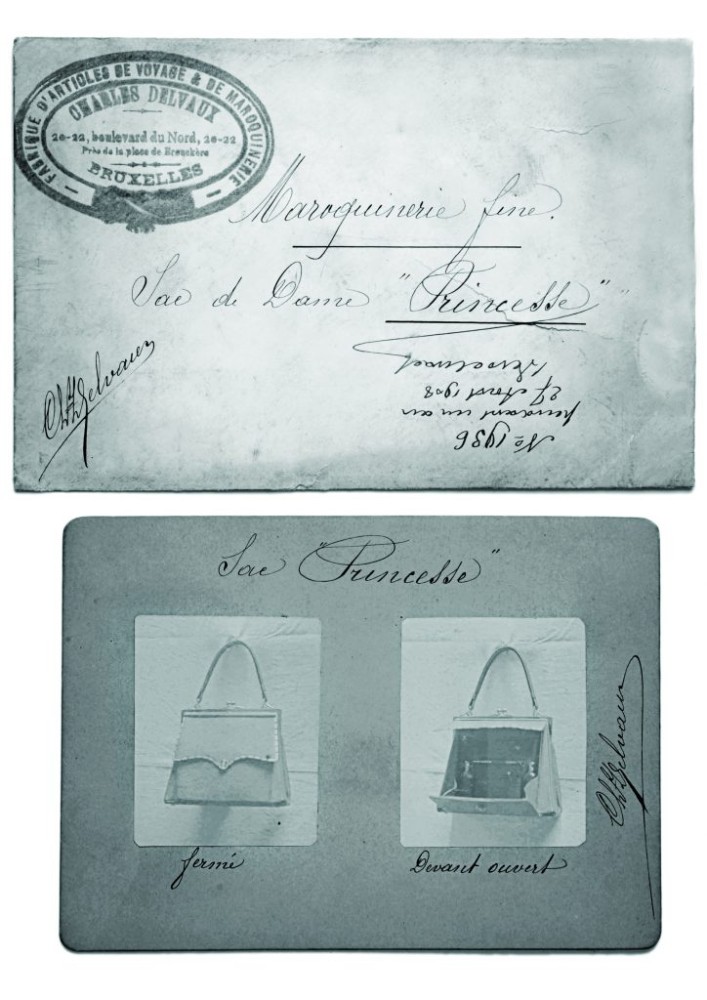

Apparently, yes. According to Luxe Collective, a pre-loved luxury e-commerce platform with 158,000 YouTube subscribers, true luxury exists in the “ultra-luxury-priced” accessories brand Delvaux. Founded in 1829 by Charles Delvaux, one year before the formation of the Kingdom of Belgium, Delvaux is the first luxury leather goods house in history. The maison holds another first in the form of its leather handbag patent, which was the earliest of its kind,

filed by the label in 1908.

Delvaux began its life as a trunk maker. The second industrial power in the world in the 19th century after Great Britain, Belgium was the first European country to embrace trains after they were invented and had the most developed railway network on the continent. At the Delvaux atelier in Brussel’s Etterbeek is the brand’s museum where a totem pole of trunks greets visitors upon entry.

These trunks trace the brand’s journey from carriage trunk maker – rounded lids to accommodate for rainwater being the obvious demarcation – to the boxier, flat lids of train trunks which began to come in various shapes from large to small and in leathers and crocodile. This golden age of travel, which saw both men and women traversing the globe, brought about the need for smaller bags and in 1908 Delvaux created the Princesse handbag in honour of the Belgian royal family for whom the brand was, and continues to be, an official purveyor.

Also see: Mikimoto: Pearls are everyone’s best friend

These days, the brand’s selection of handbags includes its iconic Brillant bag, which was created in 1958 for the World Expo in Brussels. Crafted from 64 separate pieces of leather and hardware, the bag takes over 15 hours to make by hand. It’s a heavy piece even when empty. The entire intricate process is laid bare at Delvaux’s atelier, set

in a converted hangar, where a group of craftsmen painstakingly oversee and execute each step of the bag-making process.

Before the skins are even laid out for inspection, dictats pertaining to quality and colour have already been followed by the tanneries charged with sourcing the best skins for the house. Colour swatches confirmed for new bags are clipped for the tannery to ensure standardisation across all bags made. Only the best skins are selected for Delvaux, according to guidelines that preserve the leather goods maker’s exacting standards.

Once the skins make it to Etterbeek (around 80% of Delvaux’s bags are made of calf leather from deer, with the remainder being exotics, which we weren’t allowed to photograph, but trust me, these skins are quite something to behold), they’re “read” using the naked eye to detect flaws, which are marked with white pencil. The experts who read the skin then mark out the parts most suitable for different parts of the bag they’re tasked with – one example would be that the neck of the deer is most frequently used for bag handles as the already supple nature of the skin from the animal’s own turning of its neck, makes it uniquely suited to the curvature of a handle.

One bag requires a minimum of two skins and to prevent waste, cutting is done by laser and each skin is matched in order to be as identical as possible so that all the skins can be joined together with minimal difference. Possibly the main reason why each bag is quite heavy even before anything is put inside is because they are lined with leather and interior finishings are not done in canvas or lighter materials. The entire piece is constructed and reinforced with leathers.

Assembly requires similar rigour. Artisans, who sit on the ground floor of the hangar under dramatic skylights showing the mostly cloudy skies of Brussels, first lay out all the pieces of one bag. They then complete the finishes required for the bag before it is sent for stitching. Every piece of leather has three layers of colour applied to it during the finishing process and each layer of colour is sanded before the application of the next layer. All edges are hand-finished and -painted. The process is so painstaking that artisans are asked to switch styles every month so they do not become fatigued.

When the bag is sent for stitching, the first stitches are, of course, not done with thread. In order for the stitches to respect and conform to the individual shape of each handmade bag, the holes are pierced with a hot tool in order to create clean holes through the leather. The work requires meticulous attention in order not to burn or ruin the leather. Only once all the stitching holes have been pierced can the thread go through.

The fundamental principle behind the brand’s devotion to craftsmanship when so many other brands have found ways to cede their expertise to machinery is its commitment to the legacy of its pieces, which can be seen in the over 100 on display in the museum as well as its commitment to restoring pieces that have been passed down through generations of families.

In its quiet way, the brand has lasted almost two centuries and battled through waves of logomania and maximalism. At its heart is an implicit understanding that quality and longevity go hand in hand and those who understand its language find commonality in their insider ability to identify the qualities that set the brand apart. And, while this sudden wave of quiet luxury may not drown out logos and branding, it seems a promising return to subtler, easier codes of dress alongside comfort and a big dose of quality.

Also see: The spring/summer 2023 runway report