Frank Gehry, one of the most celebrated and influential architects of the modern era, has died at age 92. Below, 10 of his most significant architectural works that define his legacy

The design world has lost a legend. Renowned architect Frank Gehry has passed away on Friday, 5 December, at the age of 96. Since rising to prominence in the late 1970s, Gehry has earned his place in the hall of fame of contemporary architects through a wealth of groundbreaking designs. Over the decades, the Canadian-American architect has left his mark across the globe, from the iconic Guggenheim Museum Bilbao in Spain to a shape-shifting residential tower in downtown Manhattan.

His work is instantly recognisable, defined by cutting-edge materials, unconventional forms, and a distinctly modern yet playful sensibility. Often associated with the deconstructivism movement, which challenges traditional ideas of harmony and order, Gehry was undeniably a pioneer. His designs defied conventions, always pushing the boundaries of what architecture could be.

As we reflect on Gehry’s extraordinary legacy, we’re revisiting the buildings that defined his career – from world-famous landmarks to hidden gems. His bold vision will continue to inspire generations of designers to come.

Gehry Residence, Santa Monica, California, 1978

It was Gehry’s own home in Santa Monica, California, that marked his entrance onto the architecture scene – only his neighbors weren’t too happy about it. That’s because Gehry and his wife, Berta, had bought a 1920s Dutch colonial-style bungalow and, in a radical architectural gesture, customised it. Rather than demolishing the house or adding on to the existing structure, however, Gehry built around it, using off-the-shelf materials in the style of the early modernists. The chain-link fencing, corrugated metal, plywood and glass that he used for the shell would become hallmarks of his early work, though some would argue that they gave the house an unfinished feeling. Gehry himself referred to the style as “cheapskate architecture.” Though his updates might’ve been controversial at the time, this space was arguably the beginning of his prolific portfolio.

Vitra Design Museum, Germany, 1989

Gehry’s first completed building in Europe, the museum and warehouse he designed for Vitra – the pioneering Swiss furniture company – represented a creative pivot point, marking Gehry’s transition from rough-edged, industrial bricolage to sculptural spectacle. Its tumble of white plaster forms – cubes, cylinders, sweeping curves – seem to freeze mid-collision, as if the gallery had been torn apart by seismic forces. The structure also helped launch a string of impressive experiments on the Vitra campus, including buildings by Zaha Hadid, Tadao Ando, Nicholas Grimshaw, Álvaro Siza, Herzog & de Meuron and more.

Weisman Art Museum, Minneapolis, 1993

Perched on a bluff above the Mississippi River at the University of Minnesota, the museum was a trial run for Bilbao and Disney, without the help of advanced digital tools. Its stainless steel facade unfurls toward the river in faceted, reflective forms that contrast with the building’s campus-facing facade, a series of various-sized cubes wrapped in earth-toned brick, matching the rest of campus. Inside, a series of flexible galleries support changing exhibitions. The museum is named for Frederick R. Weisman, a Minneapolis-born entrepreneur, art collector and philanthropist.

Dancing House, Prague, Czech Republic, 1996

When Gehry was called on to create an icon for Prague on a tiny lot, the site of a building destroyed during World War II, the architect came up with one of his most daring statements to date, designed in collaboration with Czech architect Vlado Milunić. Made of 99 concrete panels, each differently shaped, the structure’s front facade juts out as if it were made of two entwined human figures, earning it its nickname “Fred and Ginger”, after the famous dance duo Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers.

Guggenheim Bilbao, Spain, 1997

Bilbao had already been getting an architectural makeover when Gehry’s game-changing, unforgettable, fish-shaped art museum landed on its riverfront. The museum instantly made the former industrial city an alternative to Rome and Paris for highbrow art-and-architecture tourism. The project provided Gehry with that rarest of clients who allowed him to test out methods and concepts he had been evolving for decades. The architect Philip Johnson compared what resulted to Chartres Cathedral, no less. It may not last 800 years, but it is the building that will forever define Gehry – and architecture at the turn of the 21st century.

Walt Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles, 2003

Dreamed up by Walt Disney’s widow, Lillian, in 1987, the project wouldn’t be completed until 2003. But it was worth the wait. Now the cultural and visual anchor of downtown Los Angeles, Disney’s riot of titanium sails reflect rippling waves of music, Gehry’s love of sailing, fish scales and other nautical themes, as well as the frenetic city around it. Inside, the boat-like, wood-clad hall has an intimate, vineyard-style seating arrangement, with its superb acoustics shaped by Yasuhisa Toyota. Don’t forget the 6,134-pipe organ, which resembles a box of exploding French Fries. Lillian Disney, a connoisseur of flowers, would die before the hall was finished, but its hidden rear garden is centered around the “Rose for Lilly” fountain, composed of thousands of broken blue and white Delft china pieces.

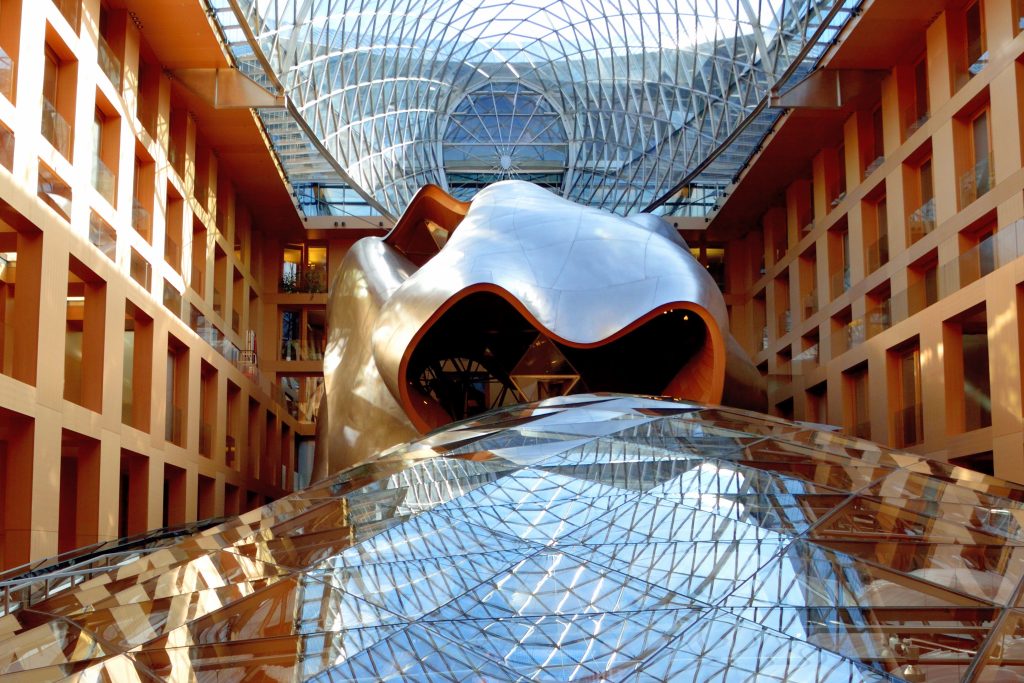

DZ Bank Building, Berlin, 2000

A stone’s throw from the Brandenburg Gate, DZ’s stone facade aligns seamlessly with its blocky neighbors on Pariser Platz, providing little hint of its shocking interior. While Gehry might’ve been known for his eye-catching exteriors, the DZ Bank proves it’s what’s on the inside that counts. A stone’s throw from the Brandenburg Gate, the building has a limestone façade that aligns seamlessly with its blocky neighbors on Pariser Platz. However, when you step inside, you’ll be confronted with a curved stainless steel conference hall, clad with a riot of warm wood panels that has often been compared to a horse’s head. Locals nicknamed the split-personality building the “Whale at the Brandenburg Gate.”

8 Spruce, New York City, 2011

Gehry’s first skyscraper marked a new era of residential towers in New York City. At 76 stories, it was one of the tallest residential buildings in the world when it opened, rising above downtown landmarks like the Woolworth Building as a symbol of the rebirth of Lower Manhattan. The twisting steel structure is made of 10,500 steel panels, almost every single one a different shape, so that the form of the building appears to change depending on the vantage point – almost like the ripples of a mirage.

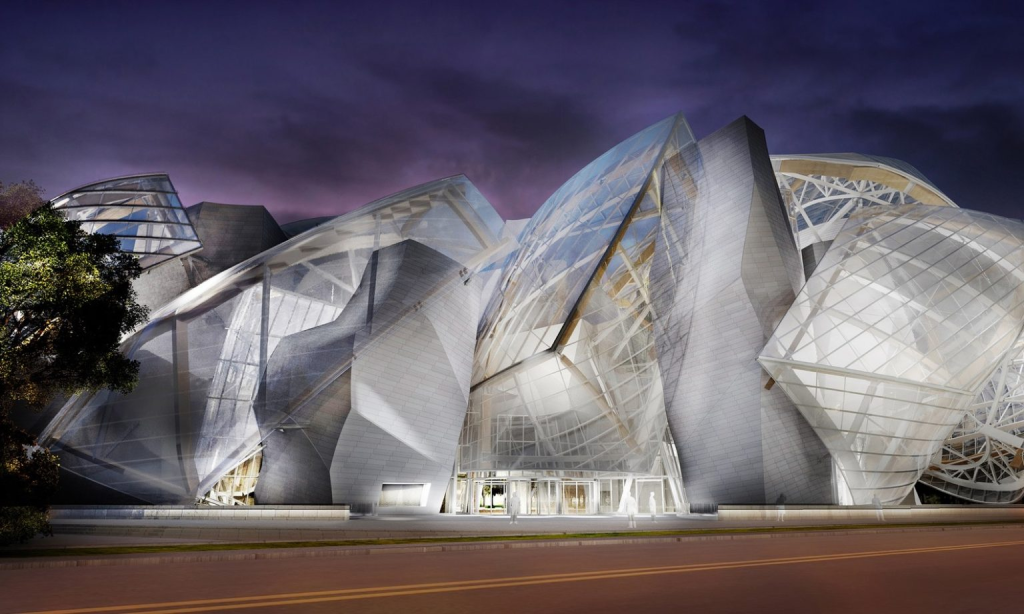

Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris, 2014

With the Louis Vuitton Foundation, Gehry swapped steel panels for billowing glass to devise one of his most graceful extravaganzas. The foundation sits at the edge of the Bois de Boulogne, the Paris park. It takes inspiration from earlier glass buildings in Paris like the belle epoque Grand Palais. Designed to take a sail-like form, the building is composed of complex geometric shapes made of glass and steel, giving it a sense of weightlessness and grandeur. This building’s unique design is characterised by the dynamic interplay of light and shadow, creating a visually engaging and constantly changing environment for visitors. As at Bilbao, exhibition rooms mix conventional, rectilinear spaces with highly sculptured ones.

Biomuseo, Panama City, 2014

After the success of the Guggenheim Bilbao, Panama City’s Biomuseo was intended to reinvigorate the capital. The architect’s first Latin American commission, which he took in part because his wife is Panamanian, celebrates the biodiversity fostered by the isthmus of Panama. Located on a narrow causeway, the 43,000-square-foot building is an exuberant collection of forms surrounding a central atrium. Gehry started the design by building models with brightly coloured wooden blocks, and the resulting structure, made of plaster-covered concrete, echoes Panama’s tin-roofed houses and colourful tropical flora. The architect has called it a very personal project, and he eschewed payment, donating his services to the people of Panama.

See also: Hans Op de Beeck on ‘vanishing’ in his art