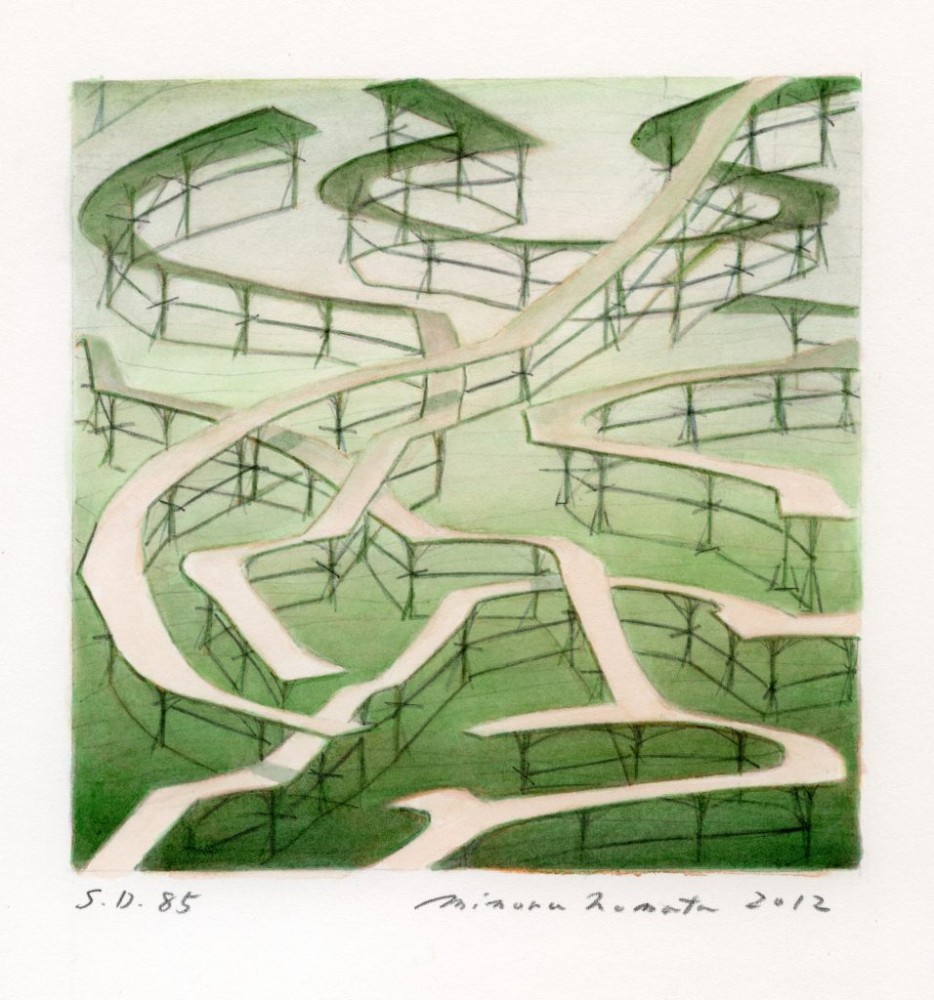

Artist by trade but architect of his own imagination, Minoru Nomata is the creator of fantastic monuments that dwarf the canvases he paints them on. With his work shown at White Cube Hong Kong from September 8 to November 13 last year, he talks to Yana Fung about absence of people and presence of time

The truest judge of art is the impression it leaves on the viewer. In cases of great art, it’s been said to be able to move people to tears. Minoru Nomata’s paintings don’t so much leave an impression but rather haunt those who see them in their architectural perfection. Despite never having studied architecture, Tokyo-born and -based artist Nomata portrays buildings with realism and precision, making them all the more lifelike and imposing.

During his childhood in Meguro, an industrial district of Tokyo, Nomata bore witness as Japan underwent significant change. From his parents’ small factory to the local woodworking factory, Nomata spent his time watching craftsmen at work, which went on to shape the industrialism evident in his paintings.

Now, Nomata’s paintings have made their way to Hong Kong, whose architecture almost echoes his own. Titled Unbuilt, the exhibition at White Cube marks the artist’s first solo venture in Greater China. It features works spanning 1987 to 2020, brought together from various series and showing an evolution of design from looming, archaic structures to quasi retro, gleaming beams of light.

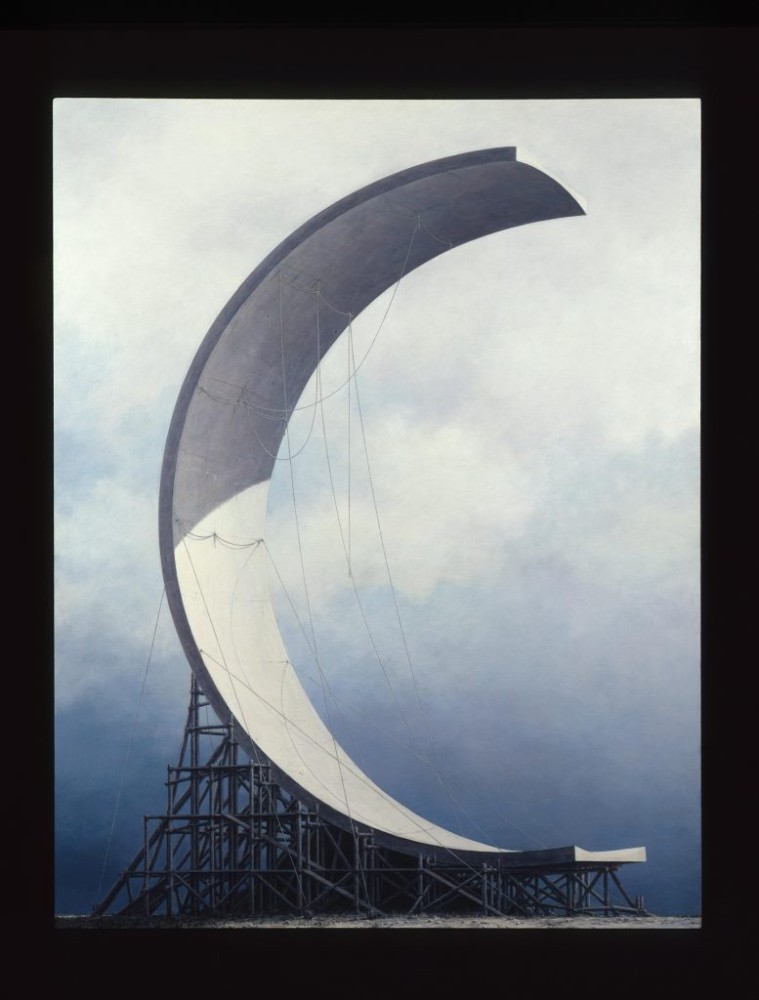

Colossal structures take centre stage and fill the canvas, almost bursting out of it. While the verdict is out on whether his paintings depict an apocalyptic disaster or a utopian dream, Nomata remains tightlipped. “I prefer something that is ambivalent,” he says. “The place is where everything comes together in the state of ambiguity.”

What jumps out about his paintings is the feeling of being left behind. With foreboding architecture that stands proudly without any sign of its human creators, viewers are left to wonder where all the people went. Nomata simply explains that the purposeful exclusion of people clears the view for onlookers to take in his buildings head-on.

“It’s a kind of exclusivity, a desire to be at the front line when I’m facing the creations in my work, unobstructed by anyone else,” he says. In the same way, a loving parent offers up their shoulders for children to perch on, Nomata offers us paintings that are open and awaiting our interpretation. “No one can enter my paintings as a result, but at the same time, anyone who stands in front of my paintings can make it their own.”

Perhaps it’s because he grew up in Tokyo and now continues to work there that Nomata remarks how the Japanese capital always makes him think about the past, present and future. This inescapable trifecta returns when he turns to his work. “I always work on thinking about the past, present and the future at the same time, back and forth, not focusing on a particular time,” he says.

Somewhat reminiscent of the fantastical but impractical structures showcased in World Fairs of days gone by, Nomata’s buildings manage to encompass the futuristic shine of sci-fi. “I’ve been working with architecture to depict ‘atmosphere’ or ‘ambience’ rather than the ‘form of the structure’, and one of the things I’m always keeping in mind is the presence of time,” he explains.

It would seem that no time has had more of a presence than our uncertain ones. Nomata’s empty landscapes become eerily familiar after months spent in lockdowns around the world left streets empty. Of course, these

paintings should in no way be taken as prophetic messages from the beyond.

“I didn’t even think about predicting the sceneries. It might sound imprudent, but when I saw the cities without

people, what I felt was that a reset had taken place in the world rather than uncomfortableness or strangeness,”

he says. In some ways, he’s not so far off. A reset has happened, the shift is palpable and now Nomata’s visions

of abandoned structures don’t seem so unlikely.

“I always work on thinking about the past, present and the future at the same time, back and forth, not

focusing on a particular time” – Minoru Nomata

Contrary to his abandoned landscapes and in the spirit of going places, Nomata’s exhibition displays encourage the viewer to move around. Inspired by traditional Japanese chigaidana shelving, which is asymmetrical by design and typically used to display decorative pieces, the artist has displayed several paintings in the framework of these simple structures to allow viewers to take in several pieces at once.

Despite the lone-wolf nature of the buildings in his paintings, Nomata creates in a way that associates one painting with the next. “When I’m working on a particular painting, I get ideas of things I want to paint, and can’t stop making a different version of it. That might be something that comes from a spirit of enquiry,” he says.

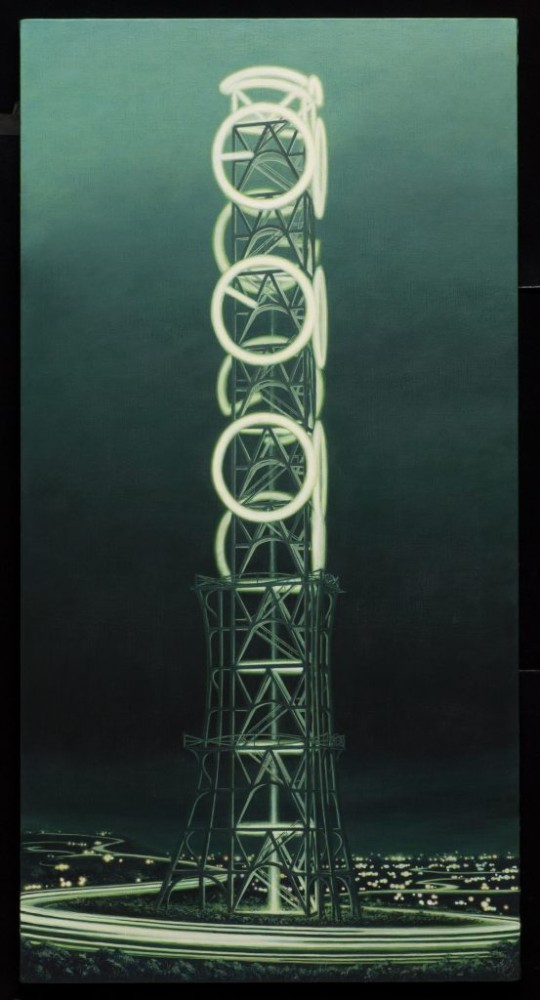

Taking his Skyglow series as an example, one glance is enough to grasp the connection between the paintings.

Magnificent towers of lights beam at you, transcending the limitations of their two-dimensional base. Set

against the dark grey walls of the White Cube gallery, the glowing effect is only amplified and together they create

imagery of beacons lighting up a smoggy night. The result is a complex interplay of colours and effects that

ultimately submerge you in brightly lit urban nights, not an uncommon sight in Hong Kong.

Unbuilt, which usually describes something that has not yet been built, takes on a different meaning for Nomata. “The title came from an architectural vocabulary, and ‘unbuilt’ is a term used to describe drawings of buildings, mainly designed by the architects of the past, that were not intended to be built – they were ‘never to be realised’ from the start,” he explains. Much like his own buildings are never to be realised, the exhibition is teeming with ‘unbuilt’ designs and, with works spanning over 30 years, Nomata ensures that some are in fact from the past.

Instead of realistic self-portraits, Nomata sometimes used his buildings to preserve his state of mind over the years. “Not always, but at some point in my early career I tried to paint buildings as self-portraits, as a means of depicting architecture,” he says. According to him, his hopes, anxieties and beliefs amid the everchanging nature of our world are reflected and recorded in his buildings. “I wanted to paint the building as an independent object. I replaced myself with various personalities and painted in a way that reflected my emotional state.”