Legend has it that the idea for Netflix came after its creator, Reed Hastings, was fined US$40 for returning Apollo 13 six weeks late at a local rental store. The year was 1997. Hastings, a software engineer and Stanford graduate from San Francisco’s Bay Area ventured into a new tech business after leaving his job as a chief technical officer at a software company.

Silicon Valley was on the verge of entering the golden era for internet start-ups. Hastings’ business model was simple: customers could pay a fixed monthly amount for renting DVDs and video games after subscribing online – no more trips to physical stores and no risk of late fees. Less than a year later in Los Gatos, at the foothills of the Santa Cruz Mountains, Netflix was born.

By 2005, the DVD-by-mail rental service was sending out a million titles per day across the US; four years later, it had reached 10 million subscribers. Netflix was a disrupter, playing the biggest role in the downfall of video rental behemoth Blockbuster – which refused to acquire part of the company for US$50 million in 2000 – and de facto triggering the extinction of the brick-and-mortar movie rental model in North America and beyond.

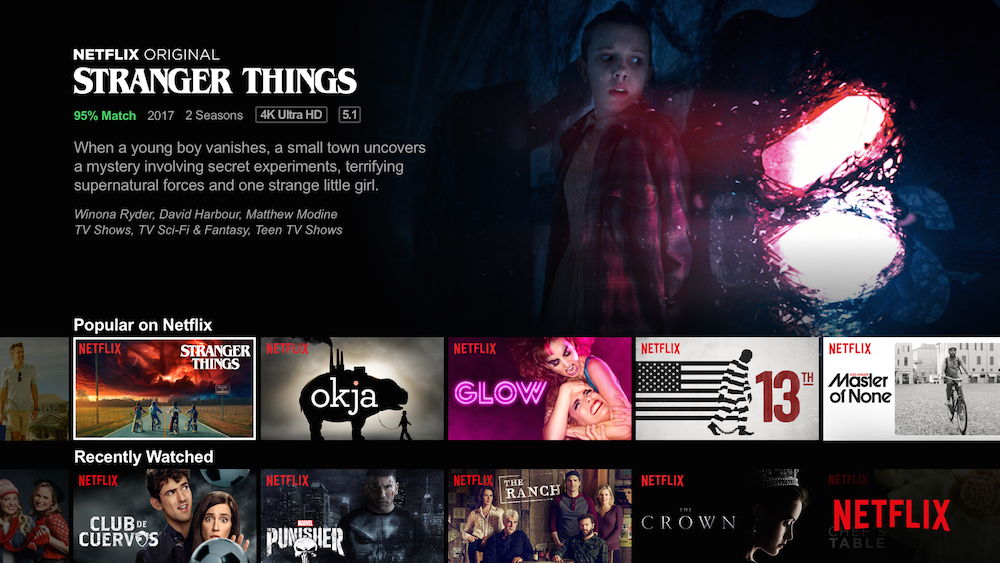

In 2007, close to sending out its billionth DVD, Hastings’ tech prodigy launched an on-demand online streaming service. Ten years and almost 110 million subscribers later, Netflix is the world’s leading internet entertainment company. Even more remarkably, it has entirely redefined the way TV is perceived, watched and created, becoming the undisputed symbol of a new era.

“Given the vast reach and the scale of coverage, it is not an exaggeration to say that Netflix has successfully built a global digital TV network – an unprecedented feat in the age of analogue television operated by conventional network television systems sharply divided by nation- states,” explains Dr Choi Jung-Bong, an associate professor at Hong Kong Baptist University’s Film Academy.

Netflix cemented its primacy in the SVOD sector (subscription video-on-demand) by devising a new personalised way of watching TV, no longer dictated by creators and networks, but by viewers themselves. According to the company, its vision “has always been

all about letting costumers gain more control over how, when, where and what content they consume.”

Flexibility, Netflix’s true forte, eventually resulted in a new term: “binge-watching”. Barely existing as a concept ten years ago, the habit of devouring all episodes of a TV show as fast as possible is now an observed cultural phenomenon associated with the rise of the platform. Watching 12 hours of television in one sitting wasn’t something many people would admit to openly before. However, what was once a moment of shame has become an enviable accomplishment.

From the very beginning, the presence and penetration of the digital streaming model into pop culture have been so profound that the younger generations have only experienced TV the Netflix way. With shows immediately available all at once, the way TV is consumed has profoundly changed. Then again, the platform wasn’t initially a direct competitor of networks and production houses, as Netflix was naturally eager to sell the rights to feature others’ content on the service. The Californian colossus, however, fomented a sweeping change in the entertainment industry at large when it premiered its first original show, House of Cards, moving the company into an unexplored territory.

The TV Takeover

At this year’s Golden Globe Awards – which took place on January 7 in Beverly Hills – most of the attendees wore black in support of the Time’s Up movement, in a remarkable collective effort to stand up against the sexist rhetoric that has dominated Hollywood for decades. Something else, however, was quite extraordinary about this year’s ceremony. For the first time, five out of the six most important TV awards – best comedy series, best drama series, best comedy actress, best drama actress, best comedy actor and best drama actor – were handed out to shows produced by streaming services. The takeover of digital TV, it’s clear, is an unstoppable force.

Of course, award ceremonies don’t uniquely dictate the reaction of the public to content, nor do they represent the sole parameter to judge outstanding works in cinema and television. However, they’re a useful metric to appreciate how rapidly the landscape has changed.

This change was initiated in 2013 by Netflix with the debut of the first season of House of Cards, the platform’s first original series. The political drama, starring Kevin Spacey and Robin Wright, was the first new show to premiere with ten episodes at the same time. It went on to make history by being the first non-traditional TV show to be nominated for a Primetime Emmy Award and ended up winning three – it was nominated for a staggering nine.

“Since 2013, the company has been at a scale where we can economically create original content for Netflix in order to meet consumers’ increasingly diversified and global taste in content,” explains Netflix. By the end of that year, the company’s stock’s value had tripled. From that point on, its strategy was essentially focused on giving creators the freedom to make high-quality shows and films without sticking to the limitations imposed by traditional networks – including season length, advertisements and pilot episodes, among other things.

Over the span of five years, Netflix has become for traditional television what mp3 players became to music: the force behind an unstoppable revolutionary trajectory. And while it certainly deserves credit for initiating the phenomenon of digital television, competitors such as Hulu and Amazon are definitely playing important roles, too, proving that the model could function in a non-monopolistic environment.

“Netflix is both the best beneficiary and architect of a large-scale shift, as it daringly got on the tide of media consumption on digital technologies,” says Choi, as I ask him whether the platform’s takeover of traditional TV is officially completed. “Netflix’s content is mostly from the US, even though it incorporates an increasing yet still limited portion of shows made in other foreign countries. The geo-cultural restraint of content production is commensurate with the narrow band of genres. Over-concentration on drama and movies is as much the source of its success as its limitation in rivalling conventional TV networks that have flourished with news programmes, variety shows and talk shows.”

While the company has recently started to diversify its content by producing its first original cooking series, stand- up comedy specials and reality shows, Dr Jaap Verheul, a film-studies teaching fellow at King’s College London, also thinks that the future success of Netflix highly depends on its ability to diversify and continue to appeal – with its original content – to audiences outside the Anglo-American cultural sphere as its evolution is now embedded “in this increasingly global but culturally homogenous media landscape.”

Challenging the status quo

In early 2017, famed director Martin Scorsese announced his partnership with Netflix to shoot The Irishman, a US$125 million gangster movie that has been in the making for more than 10 years and will reunite Joe Pesci, Al Pacino and Robert De Niro in one production. With that move, it became crystal clear that the streaming service was going all-in to catch the attention of Hollywood’s most club: the Academy Awards.

For all its power, Netflix still hasn’t scored a win – or a nomination – in a major Oscar category, though it did win one in 2017 for best documentary short for The White Helmets. The colossus has to face the conservatism that prompts many members of the Academy to work towards maintaining the status quo.

Crucially, Netflix ventured into film production on its own terms and without changing its modus operandi. So the streaming service’s original creations “have been excluded from notable film festivals and award ceremonies precisely because they do not adhere to our traditional understanding of a ‘feature motion picture’ – they are no longer produced by conventional film studios, while they are usually not exhibited in movie theatres as well,” explains Verheul.

The debate at the core of the issue is the definition of “movie” in the streaming era. The Academy’s rules state that to be eligible for an Oscar, a movie has to show in at least one theatre in Los Angeles for one week, while it can simultaneously be released on a streaming platform, echoing the guidelines of other institutions such as the Cannes Film Festival, where in 2017, the Netflix production Okja was initially excluded from the programme and denied possible awards as it hadn’t been released in French movie theatres.

The impact of the “Netflix effect” has caused aggressive reactions from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Science, which for the second time in its long history recently called for a members-only meeting to discuss the boundaries of Oscar campaigns and the extensive changes in the industry before the 90th edition of the ceremony takes place in March.

With more and more to invest in original content every year, there’s a lot at stake. “Netflix controls production and distribution, while it effectively bypasses the distribution process as it streams its content – the films and TV series – directly into the living room,” says Verheul. “In doing so, Netflix challenges not only the hegemony of major production studios, predominantly but not exclusively located in Hollywood, in providing content while it also undermines the movie theatre in bringing these films to their respective audiences.”

Much like Amazon, which won two Academy Awards last year for Manchester by the Sea after employing a traditional release strategy, in 2017, Netflix released The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected), which was nominated for a Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival and played in select theatres in October.

And of course there’s Mudbound, which was released for one week in New York City and Los Angeles in December; it’s up for four Academy Awards including best cinematography (for Rachel Morrison, the first female cinematographer in history to be nominated), best supporting actress and best song (both for Mary J Blige), and best adapted screenplay.

To an extent, this shows that Netflix is willing to slightly change its release model and compromise with major motion picture institutions to get its hands on one of those long-desired statuettes. But only when the company manages to win a major Oscar without surrendering to the traditional release cycle will its revolution be complete.

This feature originally appeared in the February 2018 print issue of #legend