With unerring intuition and an eye for truth, legendary New York–based American photographer Annie Leibovitz tells Dionne Bel how she has spent her career turning fleeting moments into lasting icons of contemporary history

For more than half a century, Annie Leibovitz has defined the art of portraiture, creating images that are as psychologically revealing as they are visually arresting.

From her early years at Rolling Stone, capturing the raw energy of the 1970s counterculture, to her cinematic compositions for Vanity Fair and Vogue, she has shaped the visual identity of modern celebrity and power. Her portraits of John Lennon and Yoko Ono, Demi Moore, the Obamas and countless others have become touchstones of contemporary culture – intimate yet monumental, precise yet spontaneous. Last summer, Hauser & Wirth Monaco presented Annie Leibovitz. Stream of Consciousness, a sweeping exhibition that revealed the intuitive rhythm of her practice – landscapes, interiors and portraits in dialogue across time. Beyond her technical mastery, Leibovitz remains a storyteller at heart, chronicling her era with empathy and curiosity. Speaking with disarming candour, the celebrated photographer reflects on her creative beginnings, the influence of her family, her process of building trust and her enduring curiosity that keeps her looking through the lens.

You moved often as a child because of your father’s career as a lieutenant colonel in the US Air Force. How did that shape your way of seeing?

It was a great childhood because you got to move every couple of years and reinvent yourself. We travelled all over the United States – Alaska, Mississippi, Texas – and looking back, it was fascinating.

I was one of six kids, and we were our own best friends. We could just pick up, move and reinvent ourselves. It wasn’t so good for everyone. My older sister found it very disruptive. But for me, I enjoyed it. I think it was a forerunner for my portraits, for my assignments, basically – going in and out of so many different places, figuring things out, starting over again.

Your mother, Marilyn, was deeply creative. How did she influence your relationship with images?

She grew up very smart – learning piano – and dance was part of it. Living in New York City, she took classes at the Neighborhood Playhouse and with Martha Graham. Modern dance was always in her life. As early as I can remember, she was taking me to dance classes. She was a creative force, a hard act to follow. My father was the opposite, and they were a great combo. He loved her so much.

Every year or two, she would make us sit down for a formal family picture. Those family photographs were very important. She was also shooting 8mm film before a lot of people. The films are all over the place technically – you can barely watch them – but it was early 8mm. That worked its way into me somehow. I grew up with her family photographs too – pictures from the turn of the century from her grandparents. They gave me an understanding of the history of the family portrait.

You originally studied painting at the San Francisco Art Institute before switching to photography. What drew you to the medium?

I wasn’t that interested in photography when I went to the San Francisco Art Institute; I was a painting major. Then my father was stationed in the Philippines and I went to visit my family during the summer. We made a trip up to Japan and bought a camera because it was the thing to do: climb Mount Fuji and buy a camera. Back in the Philippines, I used the base darkroom and started taking pictures. When I went back to school, I took a night class in photography, and as a young person, I found photography to be much more immediate and faster. The camera made me feel comfortable. Then I changed my major and started working for a young magazine called Rolling Stone. Rolling Stone built me. I was there for 13 years. It was an extraordinary beginning, learning how to be a photographer. I grew up with the magazine, the magazine grew up with me, we all grew up together.

How do you build trust with your subjects?

There’s no big mystery. I think I’m pretty direct. People sort of trust me to do what I’m going to do. I’m interested in the photograph – not the autograph or dinner. We’re all working toward the same goal: a really good picture. But it’s never easy. Every single time has its own set of problems to solve – that’s part of it, and part of what keeps it interesting. When it works, there’s a moment of connection – that’s when the magic happens.

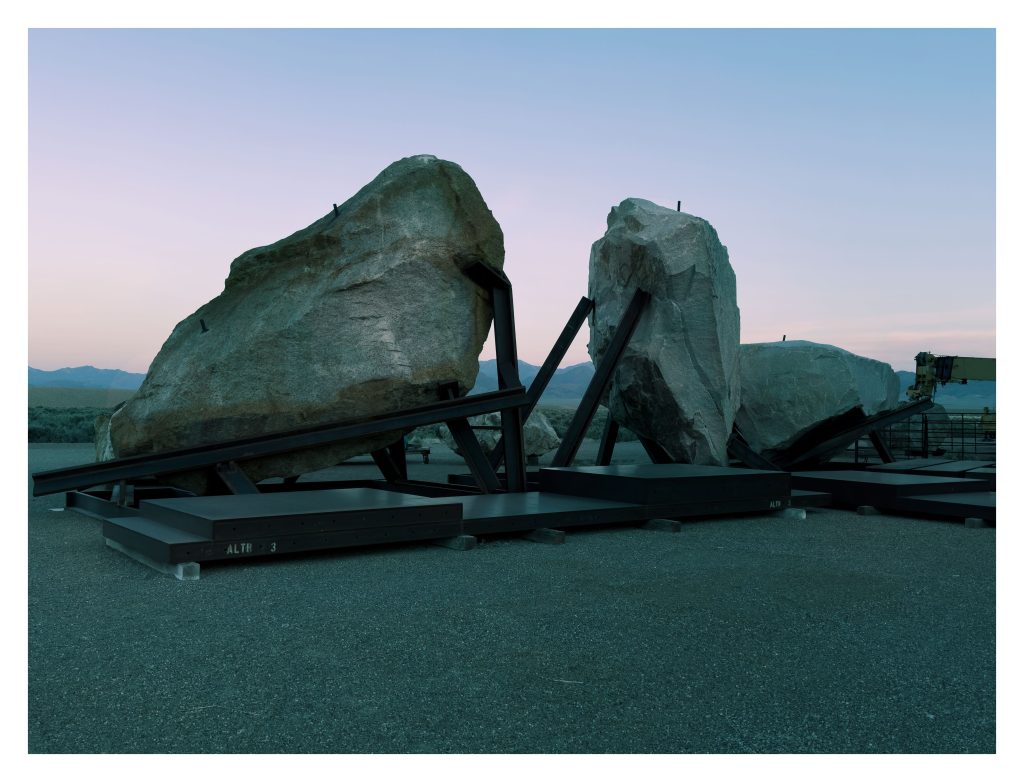

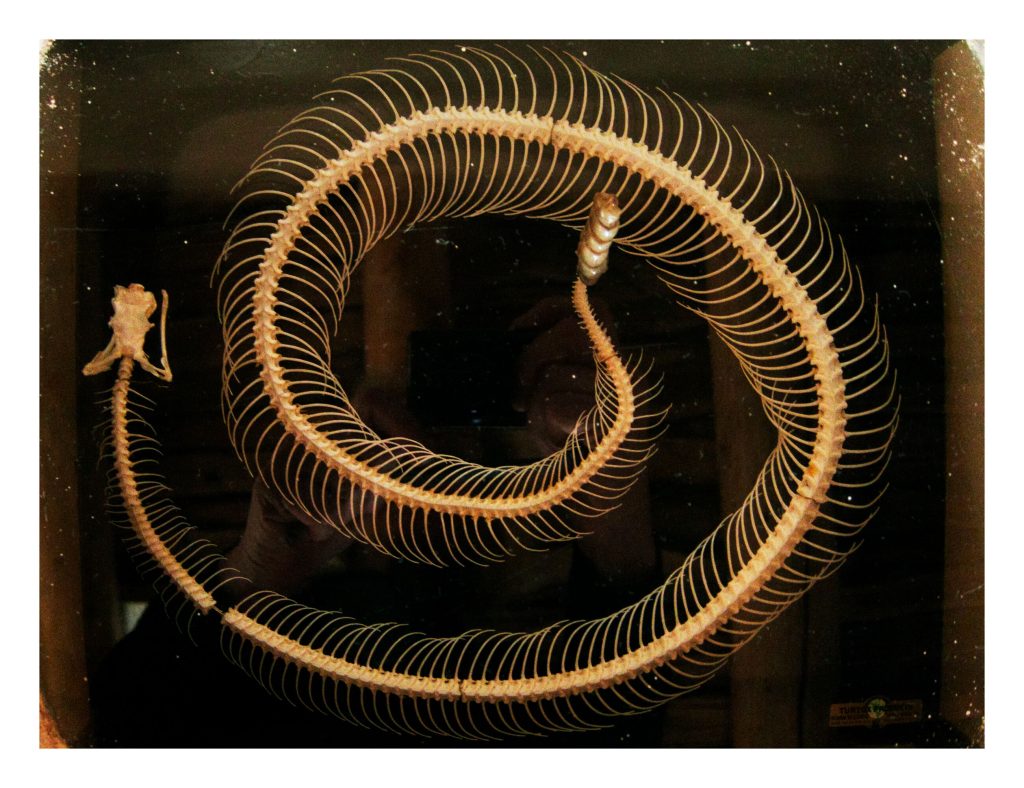

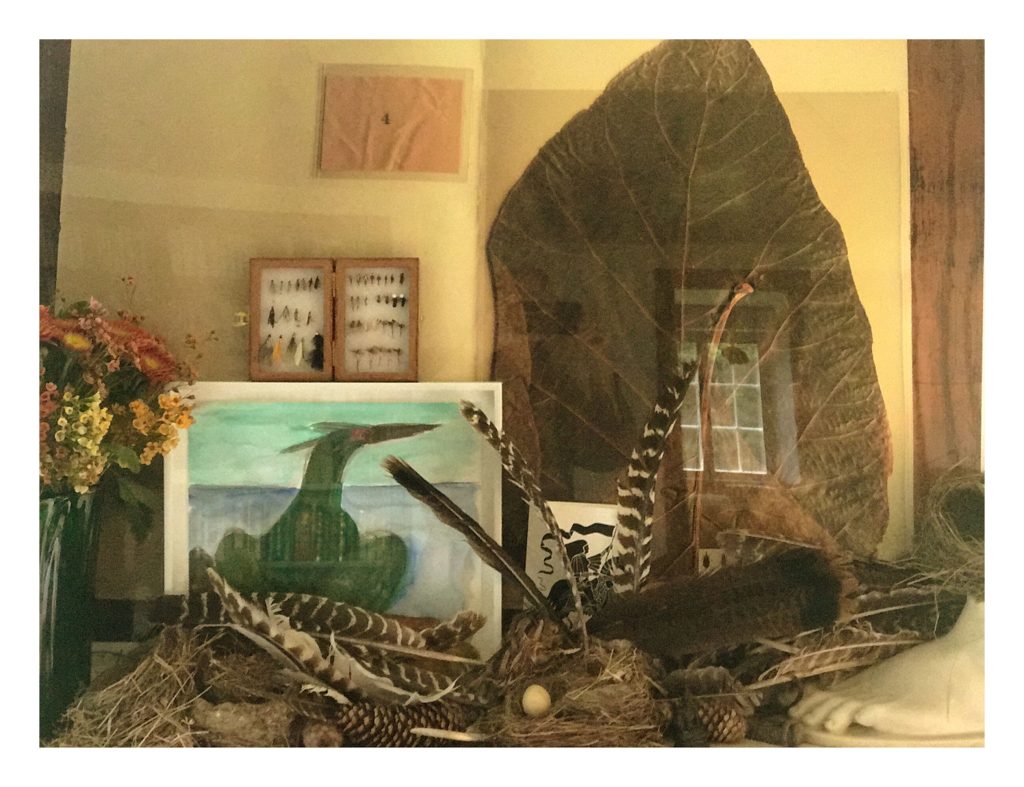

Much has been said about your iconic celebrity portraits, but you’ve also consistently returned to landscapes, interiors and still lifes. What draws you to these quieter subjects, as seen in your solo exhibition Stream of Consciousness at Hauser & Wirth, which departs from your usual chronological approach?

The landscapes came from looking for locations for people. They began to develop as their own world. You can’t really separate all these things from each other. I think it’s more present in the Hauser & Wirth show because I let it rise to the surface, but it’s there all the time – I see like that. It was interesting to see the pictures talk to each other – a whole other language developed across the work. All my work, when I assemble it for a show, is usually done chronologically because I’m dealing with time every single day, so it was interesting to think about the work out of order. It was definitely a stretch for me, but I loved it. I’m very interested in process. I love process.

Also see: Designer Joseph Walsh on wood and the beauty of creating