![]()

Few couture fashion houses can match the heft of Chanel, Dior or Saint Laurent. Beyond French national institutions, they are the global game-changers of the aesthetic, from the last century to today.

The world of haute couture may have been dressed by Jeanne Lanvin, Elsa Schiaparelli and Cristóbal Balenciaga, but none released collections which, despite being couture, touched the public quite like the French triumvirate. Chanel, Dior and Saint Laurent gave the world new words, new ideals, a new lifestyle and delivered new contours in the way we dress.

Today’s too-hot, too-fast culture of instant gratification has seen new commercial pressures placed on fashion and the rules are shifting — as are the designers, who come and go faster than seasons. Oh, and by the way, seasons are now passé, too.

No man has his eye on the pulse and the power shift — or has cut out the middleman and is so close to his customers — quite like dark angel Hedi Slimane. Slimane has worked for Dior Homme, helms Saint Laurent and has the blessing of Chanel’s Karl Lagerfeld. Slimane did for menswear in the 90s — and is still doing — what Coco Chanel, Christian Dior and Yves Saint Laurent did for women in the 20th century. The difference is he’s doing it for both sexes, from Los Angeles, and he’s showing men and women’s clothes together. Slimane is season-less, unisex and he’s controversial as Saint Laurent ever was.

In a fashion world that lives only in a perpetual round of giddy innovation and restless vanity, which begins and ends in the two things it abhors most, singularity and vulgarity, a trans-seasonal Slimane is its supreme manifestation. Disowning standards of taste, timing, elegance and edge, Hedi the harlequin, Slimane the shifter, has taken an incredibly trend-conscious and sophisticated audience, and destabilised their own secure fashion identities, set worlds colliding and become the fourth in couture’s illustrious French quartet.

Coco Chanel Anticipated the Zeitgeist of the 20th Century

![]()

Necessity is the mother of invention. It may be the greatest paradox of the opulent haute couture business that Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel, the woman who liberated her peers at the beginning of a century of consumerism, did it not by using precious silk, luscious velvet or elegant cashmere, but by elevating a textile usually used for something quite unglamorous and hardly feminine: men’s underwear.

In 1917, Vogue described the 34-year-old Coco as the “dictator of jersey” – a testament to the new-found antidote to the ornament and tight-fitting corsetry of the preceding Belle Époque.

In view of her financial circumstances, Coco bought jersey mainly because it was cheap and it suited her fashions, which were inspired by the simplicity and practicality of menswear. Jersey fell sensually upon the body, like a second skin, and was ideally suited to women becoming independent and mobile, driving cars or taking the Metro, the underground railway in Paris. Chanel, the incarnation of disruption, even gave women pockets on their pared-down cardigan suits and ample coats, so they could shed the burden of a handbag. The pockets were another borrowing from menswear, inspired by working men’s clothes. How well had Coco anticipated the zeitgeist? She employed 300 people; had premises in Paris, Deauville and Biarritz; travelled in a Rolls-Royce driven by a chauffeur; and employed a footman. In a disruptive stroke of design genius that reverberated for a century, women wore the trousers and adopted what we now call a lifestyle.

Coco didn’t stop there. Chanel No. 5 appeared in 1921, then tweed and, in 1928, the little black dress.

Chanel came to own five buildings in Rue Cambon alone and to employ more than 4,000 workers. While that was happening, Coco started a new cult. She became the poster-girl for her own lifestyle and designs. Her slim, boyish figure, cropped hair and tanned skin spoke of a dynamic, outdoor life and financial independence. Coco marketed her own style to a generation of women who’d never had such a muse to inspire them, and became the arbiter of 20th century good taste.

Like others, she closed her business during the Second World War, when France was at war with Germany, but chose to stay in Paris. Typically, Chanel was no fan of Dior’s New Look, and felt his designs were neither modern nor suitable for liberated women that had just survived the second war in 40 years.

She sought out a new team and made a notable comeback in 1953. The collection bombed. Critics hated it. But the designer persevered. Within three seasons she was regaining respect, updating her classic looks and reinventing the Chanel suit as a status symbol for a new generation. She introduced handbags, jewellery and shoes to go with it.

She died in 1971.

Although the British nobility and men’s undergarments were early influences on Chanel, the house does not dress men. What chance is there of Hedi Slimane, who is rumoured to be unsettled at Saint Laurent, going to Chanel and creating Chanel Homme, or Monsieur Chanel? Karl Lagerfeld included men’s T-shirts and briefs in his Chanel collections in 1993. Lagerfeld has a job for life at Chanel, but if he moves aside, perhaps Slimane will take the helm and steer the house into the menswear market. Chanel will have turned a full circle, returning to the inspiration of its founder, Coco, a century ago.

Yves Saint Laurent is Credited With Empowering the Women Coco Chanel Liberated

![]()

Yves Saint Laurent was a man of superlatives. He was the youngest couturier ever, the first to design a haute couture black leather jacket, the first to have a nude photograph of himself published and was the winner of the first prize in the French Wool Board competition in November 1954, with a black crepe cocktail dress he had made in Hubert de Givenchy’s workshop.

A month after taking first prize, Saint Laurent showed 50 sketches to Michel de Brunhoff, director and editor-in-chief of Vogue Paris, who showed them to Christian Dior. Dior snapped up Saint Laurent immediately. Six months later Saint Laurent’s first dress for the House of Dior caused a sensation and was immortalised in photographer Richard Avedon’s Dovima and the Elephants.

Two years after that, Dior died of a heart attack, and on November 15, 1957, the 21-year-old Saint Laurent replaced Dior, becoming the youngest couturier in the world. Saint Laurent’s first collection after taking charge, January 1958’s Trapeze, earned him recognition, a Neiman Marcus Award and his first meeting with Pierre Bergé.

By 1960, Saint Laurent had designed theatre costumes for Roland Petit, of Repetto brand fame, presented the first haute couture black leather jacket, had been called up for military service and replaced at Dior by Marc Bohan. Saint Laurent was then confined in hospital for six weeks, and suffered a nervous breakdown.

![]()

Two years later he had set up his own fashion house with Bergé. Four years after that Saint Laurent started the Saint Laurent Rive Gauche ready-to-wear label, giving it the same attention as his couture. About the same time, he introduced Le Smoking, his legendary smoking suit. He came out with his sheer blouse in 1966 and the jumpsuit in 1968.

In 1971, the designer’s radical collection, dubbed the 1940s collection, shocked animal lovers and fashion critics. Saint Laurent also launched his first perfume for men, Pour Homme. To sell it, he posed naked and the publication of Magnum photographer Jean Loup Sieff’s picture brashly challenged taboos about male nudity in advertising.

Saint Laurent was made a knight of the Legion d’Honneur in 1985. In 1998, he showed his last Rive Gauche ready-to-wear collections, but carried on with haute couture until 2002. At his last show, he took a tearful final bow as his cinematic muse, Catherine Deneuve, belted out Ma Plus Belle Histoire d’Amour. Saint Laurent died in 2008, at the age of 71, but his legacy endures. Over the next two years, Bergé will open two museums, one in Paris and the other in Marrakech, which will commemorate his partner.

Saint Laurent harnessed art for his purpose. He drew on Mondrian for one famous dress, and on Van Gogh’s Sunflowers and Irises, and his creations made references to Picasso, Matisse, Cocteau, Braque and Warhol. By invoking male dress codes, Saint Laurent invested women with social power while preserving their femininity. Coco Chanel called Saint Laurent her spiritual heir.

“If Chanel gave women their freedom, it was Saint Laurent who empowered them,” says Bergé.

More Than a Look, Christian Dior Created an Outlook for a Generation Tired of War-Torn Rags

![]()

If there was ever a designer that was a one-hit wonder, it was Christian Dior. Dior’s 1947 New Look had rounded shoulders, cinched waists and very full skirts — celebrating ultra-femininity and opulence in women’s fashion. After years of military and civilian uniforms, sartorial restrictions and shortages during and between the two world wars, Dior’s offering was more than just a new look. It was a new outlook, the trappings of a new lifestyle.

It could all have been very different. Born in France in 1905 and brought up in Normandy, Dior moved with his parents to Paris when he was 10. He wished to study architecture, but his father pressed him to study political science. Dior then served in the armed forces. In due course he opened a small art gallery and in the years he ran it he showed works by Pablo Picasso, Jean Cocteau and Max Jacob.

Dior started his design career only in 1935, when he began selling sketches, which helped win him a job with Figaro Illustré. The designer Robert Piguet hired him in 1938. During the Second World War, Dior served in the south of France, then returned to Paris in 1941 and worked for Lucien Lelong in a much larger design house.

![]()

Lelong was a phenomenon, a man credited with keeping la couture in France and out of the grasping hands of the German occupiers during the war. Lelong employed Dior, Pierre Balmain and Hubert de Givenchy before their names became famous globally. “It was from Lucien Lelong I learned fabrics have personality, as varied as that of a temperamental woman,” Dior wrote.

He left in 1947 to set up his own house with the backing of textile manufacturer Marcel Boussac. Dior lured fashion illustrator René Gruau away from Lelong, to give his game-changing New Look silhouette a vivid, artistic feel. Gruau continued to draw for Dior for the rest of the 20th century.

Dior helped restore beleaguered post-war Paris as the capital of fashion. Each of his collections had a theme. The spring 1947 collection was called Carolle or Figure 8 – the latter suggesting the silhouette of the New Look, with its prominent shoulders, accentuated hips and small waist. The spring 1953 collection was dubbed Tulip, and featured an abundance of floaty, flowery prints. The predominant feature of spring 1955’s A-line collection was just what the name indicated, with its undefined waists and smooth silhouette that widened over the hips and legs.

![]()

Some of Dior’s designs simulated Second Empire and other historical styles, but he also created trompe-l’oeil detailing and soft-to-hard juxtapositions, making them part of the modern wardrobe. In his final collections, Dior felt the need for a more limber silhouette and lifestyle, and designed narrow tunics and sari-like wraps

What was game-changing was not just his designs, but also the way he approached his business. With his partner Jacques Rouet, Dior pioneered licence agreements in the world of fashion. By 1948 he had done lucrative licensing deals for furs, stockings and perfumes, which not only generated revenue but also made him a household name.

While the House of Dior is still a thriving business today, the designer’s untimely death in 1957 left the world of fashion without a great dictator of style. Dior designed under his own name for only a decade, but his influence and methods still pervade fashion. Bernard Arnault, the billionaire boss of the LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton luxuries conglomerate, regards Dior as the pride of his stable of brands.

Hedi Slimane Already has a Touch of Saint Laurent and Dior in His Work, and May Yet Add a Dash of Chanel

![]()

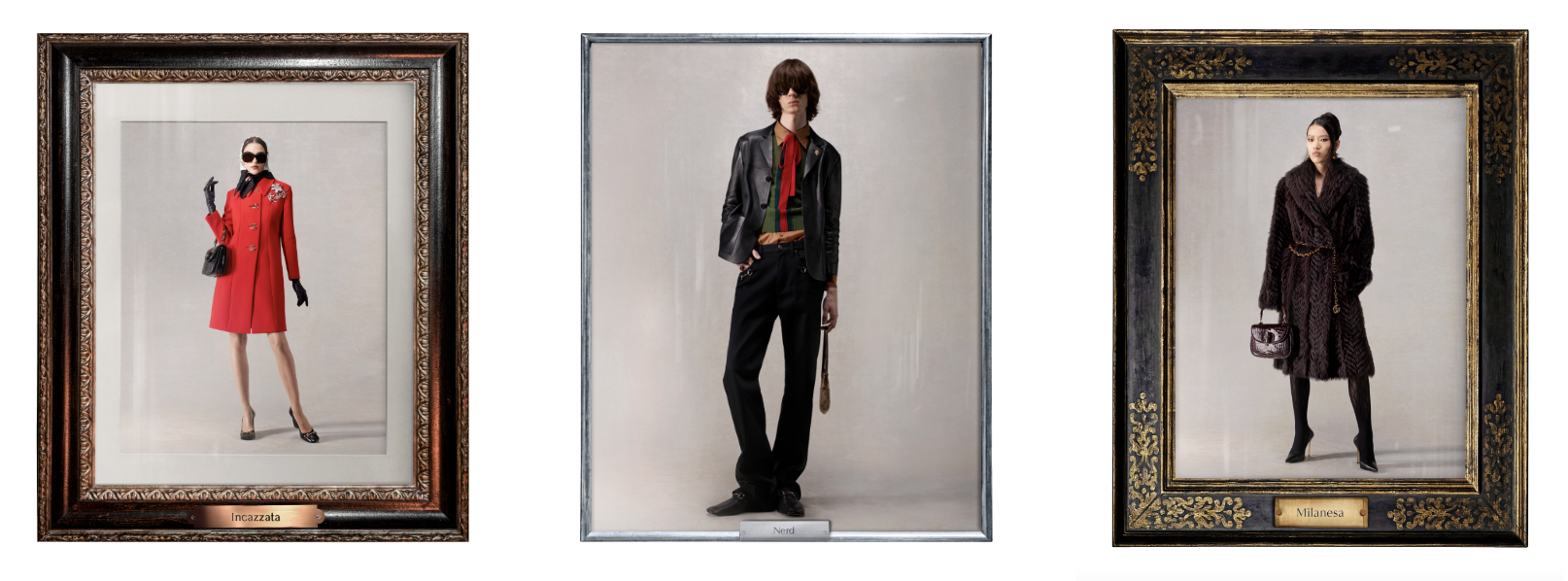

Let’s dispel one misconception straight away: Hedi Slimane was not being flash and brash when he took charge of Yves Saint Laurent’s couture house in 2012 and dropped the word Yves from the brand name. Slimane’s deed outraged most members of the fashion media. T-shirts were printed bearing a protest against the omission: “It ain’t Laurent without Yves”.

#legend would like to make it known that Slimane was being sensitive and reverent. When Yves established his brand with Pierre Bergé, he said the name of the company should be just Saint Laurent because Yves Saint Laurent was too much of a mouthful for anybody that wasn’t French. So Slimane’s dropping of the co-founder’s first name merely granted a 60-year-old wish. After all, Saint Laurent himself called his 1966 ready-to-wear line simply Saint Laurent Rive Gauche.

The media outrage and T-shirts obscured the first-rate relations between the Saint Laurent house and Slimane, which have prevailed since the day he joined it. Slimane used to help friends with fashion shows, and so came to the attention of Bergé — much as Saint Laurent had half a century earlier. Bergé hired Slimane in 1996 as a member of the Yves Saint Laurent menswear team. Within a year, Slimane had become head menswear designer.

![]()

But within no time, he taken an abrupt “Diorversion”, to a place called Dior Homme. Slimane’s razor-sharp silhouettes, his slim-man chic, changed the wardrobes of men the world over. One of whom, Karl Lagerfeld, having seen what his capacious proportions were depriving him of, lost 18 kg just to squeeze into Slimane’s fashions. Slimane and Lagerfeld have been close friends since. Lagerfeld’s publishing firm, Editions 7L, published Slimane’s book of photographs, entitled Berlin, in 2002. But no sooner had Slimane made the cut at Dior Homme than he quit the business to pursue another of his loves, photography, with a photo documentary on Pete Doherty, Britain’s bad boy of rock.

Slimane was lured back to Yves Saint Laurent in 2012. He revamped the house’s logo and, controversially, moved its headquarters from Paris to Los Angeles. Since the beginning of this year there have been rumours about Slimane’s future at Saint Laurent. That is strange, in view of his success with the house.

He sharpened up two of the co-founder’s best-known creations: Yves’ Le Smoking tuxedo, and the biker jacket from the Beat collection (1960), as anyone who saw his February ready-to-wear extravaganza in Los Angeles would know. Skinny jeans, boots, printed shirts and a skinnier scarf here and there make the new Saint Laurent silhouette.

Perhaps Slimane himself started the rumours about his future at Saint Laurent, just to be provocative. Perhaps he will return to Dior. Perhaps he will join Chanel as Karl Lagerfeld’s subaltern and establish a Monsieur Chanel while he waits for the main man to vacate the creative directorship. Or perhaps Slimane will go the way of the founders of Chanel, Dior and Saint Laurent and set up his own house. Slimane is enough of a pioneer and aesthetic transformer to distil the essence of one hundred years of fashion and create a new spirit that will inspire the 21st century lifestyle.