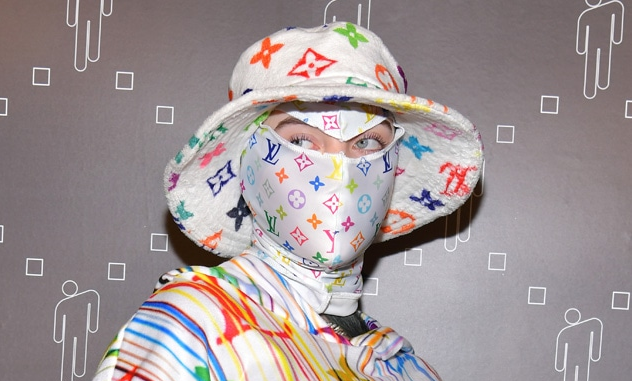

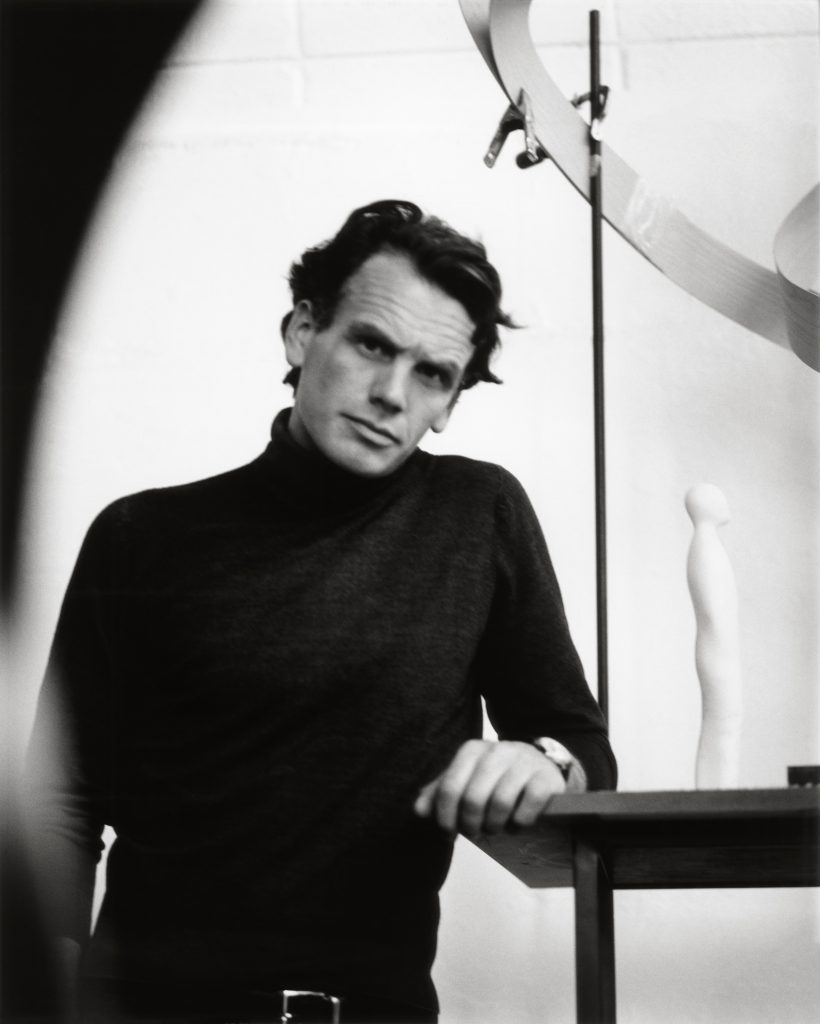

Known for his bespoke furniture and site-specific commissions in free-flowing forms, Irish designer-maker Joseph Walsh tells Dionne Bel about redefining the language of wood and the beauty of making

From a farmhouse in rural Fartha in County Cork, Joseph Walsh has forged one of the most distinctive voices in contemporary design.

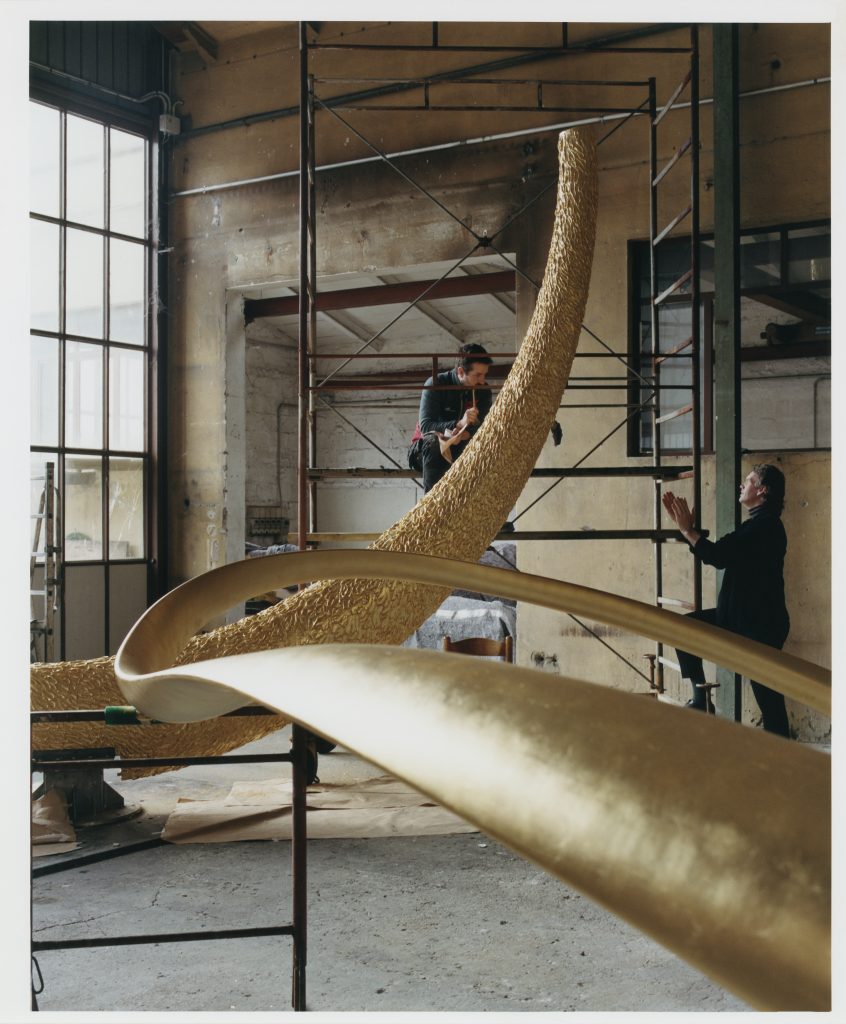

Entirely self-taught, he began making furniture as a boy and founded his studio at just 20. Today, his workshop produces sculptural furniture and monumental works collected by the Met in New York, the Centre Pompidou in Paris and private clients across the globe. His signature is the curve – fluid, organic, alive – born from layering and laminating multiple veneers in unexpected shapes in a deep dialogue with wood. Blurring the line between design and art, he shapes each piece by hand, time and a restless pursuit of new forms.

Despite international acclaim, Walsh remains rooted in this southwestern corner of Ireland, where he also convenes Making In, his annual gathering of artists, architects and thinkers. Whether creating a bed that seems to unfurl upwards like a wisp of smoke or a 10.5-metre-tall, bronze-and-oak outdoor sculpture for the Ireland Pavilion at Expo 2025 Osaka, he turns making into poetry. Represented by Tokyo gallery A Lighthouse called Kanata, his work will feature at West Bund Art & Design fair in Shanghai this month and at Art SG in Singapore in January.

What was your childhood like, and how did it shape your outlook as a maker?

I grew up on a farm in Ireland at a time when people still made things – it was the normal thing to do. In industrialised economies, generations became factory workers, but we worked with the seasons, fixing things, welding, making. For us, it was a luxury to buy something. My mum, who came from Dublin, made a big effort to create a quality of life in the countryside. She had a vegetable garden, a cow dedicated to the house and she kept connections with craftspeople, like a cobbler who made all our schoolbags. We thought they were terribly unfashionable, but she was holding on to a way of life. Looking back, that world gave me the confidence that making was not intimidating – it was just part of life.

Do you remember the first object you made?

My grandfather gave me a fretsaw when I was eight, so I did all this fretwork and cutting out figures. At 12, I made a copy of a dresser from my parents’ house. It wasn’t an exact copy; I went through my mum’s books on vernacular Irish furniture, and picked out details I liked. Of course, years later, I realised I had combined details from different provinces in the country, which was sacrilegious in a way. But at the time, it was great. My mum brought me to the timber yard to pick up timber. My folks were great at encouraging us. I think succeeding at making something young enough gives you this incredible feeling of empowerment, but also humility, as there’s a joint back there that’s not perfect. Then in my teen years, I gave up school and just made furniture.

What was your breakthrough project that set you on your path?

There have been a few milestones, but the Figure of Six chair was a turning point. I had the idea of making a chair from a single plank of wood: cut it in half, slice it into layers, bend it into a configuration like a six, then triangulate it. I proposed it for a competition for the Irish Forestry Board. They shot it down – the judges said a chair should have four legs and arms. But it led to meeting a couple from France who were excited about my approach, and it pushed me to keep developing. That was the beginning of a real design vocabulary for me, experimenting with bent wood and new techniques, which I stuck with and exploited for a period, and it gave me the courage to go further.

Your work is renowned for its weightless, sweeping curves. Where does that obsession come from?

There was a time when I became very focused on sharp, geometric forms. It was an interesting exercise, but it felt too academic. The curves came naturally – they’re simply the most natural thing to do. I tried to control the curves at first, but then I just threw the rule book out. My Enignum series came out of breaking free, and then the Lilium works explored geometric forms becoming organic – nature is like that. Recently, I co-curated the exhibition Rinn with a Japanese colleague. In Gaelic, rinn means a point or promontory; in Japanese, it means a circle or circularity. That dialogue between place, circle and cycle reflects how deeply curves are connected to how people across cultures have built and lived thousands of years ago. Today, everything is done in squares as building blocks, but trees don’t grow as planks. It’s just because of the saw that we convert them into this shape, but it’s not natural and it’s a very inefficient way to use wood.

Time seems to be a central element in your work. How do you explain its importance?

People often say time is money, but for me, time is a free ingredient. If you let timber dry longer, it becomes better and it costs nothing but patience. When we finish a piece, we let it stabilise and put it through a cycle to prepare it for destination. The more pressure you put to shorten the time, the more compromised the work becomes. I’ve learned the best projects take two, three, four, even five years. Sometimes you need to stop, let a project sit and then come back with fresh eyes. We even buy timber five to eight years ahead; the wood we’re buying now won’t be used until 2030. That relationship with time is what makes the work possible.

Also see: Erwin Olaf’s manager reflect on four decades of his art