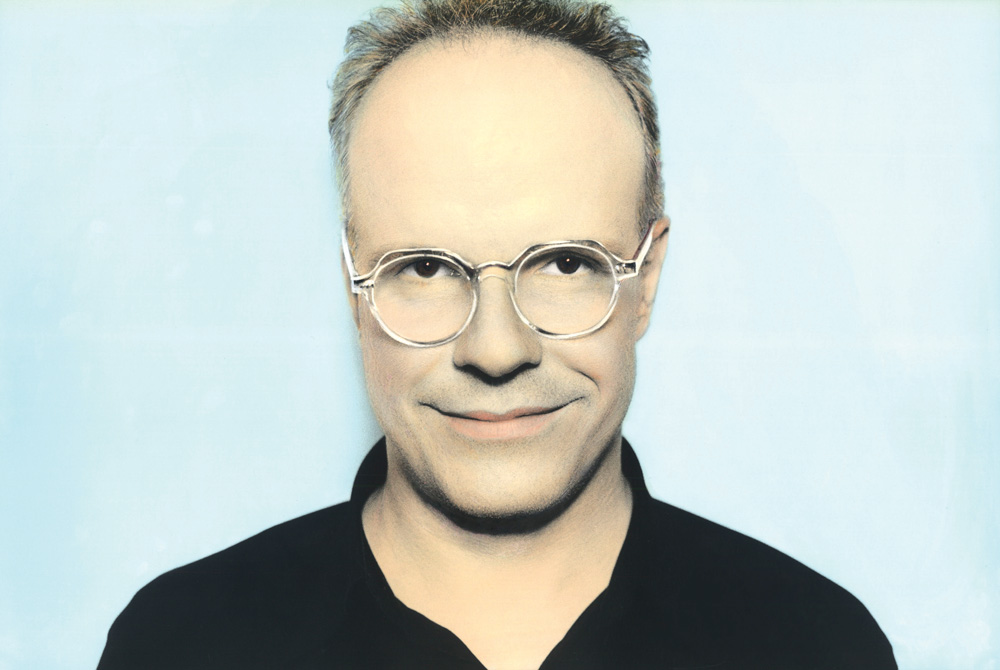

No man represents the world of art better than Hans-Ulrich Obrist, the Swiss curator and connector bringing Zaha Hadid’s work to Hong Kong.

Hans-Ulrich Obrist, the Artistic Director of Serpentine Galleries in London, is a one-man art assembly line. Since the early 1980s, the Swiss curator has been relentlessly interviewing and introducing artists, documenting exhibitions and creating an ecosystem of enterprise. Last year he topped the ArtReview Power 100 list of the most influential people in the world of art. David Zwirner was fourth on the list and Larry Gagosian sixth.

Obrist is something of a human dynamo. Most weekends he is on his travels. The 49-year-old sleeps as little as four hours a night. He asks me to call him at 6am in Mexico. The curator describes himself as a “junction-maker” between people, which is what novelist J.G. Ballard called him.

But Obrist is too modest to say that he sets the agenda. He may be close friends with Klaus Biesenbach, director of MoMA PS1 in New York, but he lacks Biesenbach’s superstar status. “The agenda will always come from the artist,” Obrist says. “But it wouldn’t be my role to take the lead. It has to be more humble, more utilitarian. We need, in the 21st century, a more feminine approach to art and curation.”

Swire Properties has a history of introducing Hong Kong to figures such as Vivienne Westwood, Frank Gehry, Tim Burton and, last year, Antony Gormley. The company and the Serpentine Galleries have got together to bring Obrist to Hong Kong this month as curator of his own show of works of art by the late Zaha Hadid, as part of Art Basel in Hong Kong. It is a flashy feather in the Swire Properties cap.

“As a long-standing supporter of the arts, we are delighted to be presenting these rarely seen works by Zaha Hadid in Hong Kong,” says Swire Properties office property director, Don Taylor. “Her experimental style resonates strongly with us at Swire Properties and we felt it only fitting that her achievements be showcased at ArtisTree in Taikoo Place, which enjoys a reputation for its world-class programming.”

Obrist echoes the sentiment. “ArtisTree is a very exciting space,”he says. “We saw that last year, with the Uli Sigg collection. It’s perfect for an exhibition, especially one that’s related to architecture in some way.”

Obrist says that even in London, while many people know Hadid to be what he calls “one of the most innovative and technological architects of the late 20th and early 21st century”, fewer are aware of her work as an artist. Yet Hadid’s art preceded her architecture by some years.

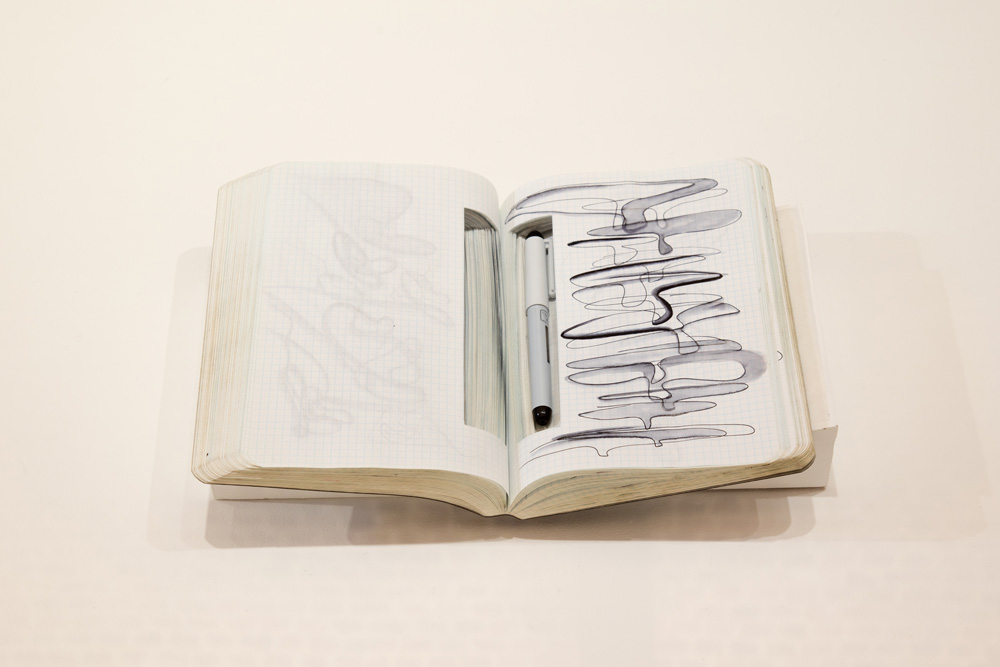

Among the exhibits in Obrist’s show will be Hadid’s notebooks. Their contents “will be a great discovery”, he says. “It is the first time we’ve shown these intimate notebooks.” Their importance cannot be overstated. “A few months before she passed away, we were going through her notebooks and talking about doing something with them,” Obrist says. He pauses, then adds: “This is the last exhibition that was planned during her lifetime”.

Obrist explains the significance of the notebooks. “Her background is calligraphy. She grew up in Baghdad. From the fluidity of calligraphy to the fluidity of the visual age, she combined ancient ways with contemporary ways. The notebooks are an incredible treasure, an incredible source of inspiration, and, of course, there is also the connection between Zaha, Hong Kong and her earliest work.”

In the early 1980s, Zaha Hadid Architects submitted a proposal to build in Hong Kong what would have been called The Peak Leisure Club. The structure would have been a man-made mountain of polished granite, towering above the congestion and intensity of the city below. The subterranean spaces, distinctive horizontal layers and floating voids intended for various activities were Hadid’s idea of the high life. The proposal won the competition to design the club but the project never went ahead. Hadid’s only structure in Hong Kong is the Innovation Tower in Kowloon.

Obrist says the influences on Hadid were manifold. “One clearly sees Eastern influences, calligraphy of the Middle East,” he says. Then she attended the Architectural Association School of Architecture in London, along with Rem Koolhaas, and the two remained friends, Obrist says.

“I think the biggest influence came from Russian constructivism and the Russian avant-garde. Malevich, Rodchenko, Goncharova brought together all the disciplines which they could,” Obrist says. “She was inspired by the vocabulary and mission of these early 20th century Russian artists.” The curator says this comes through strongly in Hadid’s designs for big exhibitions at the Guggenheim Museum in New York in the early 2000s.

“She used the past to reinvent the future, very much used the avant-garde toolbox to directly venture into the 21st century,” Obrist says. “They are so contemporary that they could have been done now. She has very early on anticipated our visual age, in a premonitory sort of way.” Koolhaas would agree. The Dutch architect once said of Hadid: “I really liked the way – and this maybe was her greatest, unique, contribution – that she was mobilising a part of the past to construct the future in a kind of seamlessness that was almost as seamless as her work became. This is what I would have to say about her work.” Some believe Hadid’s use of perspective and space in her paintings pre-empted virtual reality.

Obrist thinks the work of Malevich and Duchamp were strong influences on Hadid. “They changed the rules of the game. I think they resonate until today,” the curator says. “It’s amazing how many artists were inspired by Duchamp. Even yesterday, I was at an exhibition by Gabriel Orozco. The idea of the readymade, the art of the readymade, is still profound. In relation to Zara and Russian art, it’s less about the Black Square, more about art and architecture being able to penetrate all aspects of society,” he says.

“Zaha is a leading artist, architect and also a leading designer; industrial design, general design and furniture,” Obrist says. “She built our building, the Serpentine Galleries, the annex, cafe – a free-flowing structure. You can experience her as architect and designer. She collaborated with Google on 3D, virtual reality and technology. That idea of these many dimensions, her gesamtkunstwerk, a complete or all-encompassing artwork, was the key thing she got out of the Russian avant-garde.”

It is reminiscent of Le Corbusier, who, like Hadid, was an artist as well as an architect. “In a way, their architectural work could not be more different,” Obrist says. “Zaha appreciated fluidity, very different from the language of Corbusier. But I would say you’re right because Le Corbusier was one of the very few architects who was an artist. I think he is one of the most important architects of the 20th century. But he wasn’t a game changer in terms of visual art. With Zaha, her paintings, drawings, calligraphy could be installed next to any masterpiece. It’s not a secondary art. She’s not a great architect who also was an artist, she’s also a great artist.”

Obrist says relics such as notebooks contain history recorded as it happened and so should be treasured. “We should not forget, in our digital age, how important the process of hand-drawing is,” he says. “It’s less used in our digital age. As much as Zaha is regarded as a digital practitioner, she did an incredible amount of doodling and hand-drawing – Corbusier also. Think about the value of what they drew.”

The curator never stops interviewing and connecting artists, and trying to find new ways to show their work and culture as a whole. He is interested in handwriting, and posts on Instagram handwritten notes that he asks artists to send him. Another project he uses Instagram for is called The Future of Art. “Our mantra at the Serpentine Gallery is that there should be no end to experimentation and we think about that every morning at the gallery. Experimentation must continue. That’s our motto. Hence our project, The Future of Art.”

What is the future of art? “Interesting question. We can, of course, always look at young emerging artists. That’s part of our practice. But you never can know where the future of art is. It is always very unexpected. So I think that is a very wise quote of Martha Rosler: ‘The future of art always flies under the radar.’ There are many other definitions. I like Eric Hobsbawm’s quote about art being a ‘protest against forgetting’.”

What about the future of art in Hong Kong? “In the last couple of years I’ve been visiting regularly and I keep seeing great artists in our exhibitions at K11,” Obrist says. He describes Firenze Lai as an extraordinary artist, very political, who thinks about freedom in the city and occupies the city in her paintings.

“On the other hand, somebody like Samson Young – when you think there should be no end to experimentation – he’s a good example, as a sound experiment. He’s also an artist we admire,” Obrist says. “So, it’s a great art scene, but I think it also has been a great art scene for a long time. But, of course, it’s getting more international attention.”

I ask whether it is lack of talent or lack of marketing – or both – that confines the reputations of Hong Kong artists to Hong Kong. “Artists often go their own way,” Obrist says. “You could argue, if they do great work the world will eventually catch up with them. I don’t think they have to market. They just have to do great work. One thing which might also play a role is that China has overshadowed Hong Kong,” he says.

“There is also an issue of space,” Obrist says. “Art needs space, and it’s very difficult for artists in Hong Kong to have studio space, venues. Space is a rare commodity. It’s not like you have huge exhibition spaces.”

Obrist has a reputation for being less keen on painting than the other arts. I ask if we should we care that Belgian painter Luc Tuymans is visiting Hong Kong. “It’s great news,” Obrist says. “He’s been a great force in European art in the 1990s. There are many, many dimensions to Luc Tuymans, as a painter, as a political artist. I did an interview with him in 1993 and I’ve always been interested in his views. At a time when Europe is in crisis, he has very articulate ideas about the future of Europe and saving it through culture and art. And he’s a very important artist. It’s very, very exciting that he’s coming to Hong Kong.”

What is the human dynamo’s favourite pop song? “You know, it changes and evolves,” Obrist says. “Frank Ocean is the most recent thing I’ve been listening to.” He pauses to think before plumping for Ocean’s Novocaine. Mention of Ocean prompts Obrist to give the Serpentine Galleries a plug. “Next year we’re doing a big show. He directed the two large video clips of Solange.”

Obrist’s numerous phones are ringing and so our conversation is at an end. The curator has to get back to his junction-making and the human dynamo has to power up his art assembly line.

ZAHA HADID: THERE SHOULD BE NO END TO EXPERIMENTATION, Presented by Swire Properties, Serpentine Galleries and Zaha Hadid Design will be on at ArtisTree in Taikoo Place, March 17 to April 6, 2017. For further details visit: arts.swireproperties.com