Racing Extinction, a 90-minute documentary about how we are harming the climate and the wildlife on our planet – and how we might begin to do something to stop it – premiered on Discovery Channel around the world on December 2.

Documentaries about the parlous state of the natural world are nothing new. This one was directed by Louie Psihoyos, who had directed the Academy Award-winning The Cove. But Racing Extinction had ambitions beyond confronting audiences with evidence of our abuses. It sought not only to inform and appal, but also to inspire, and so be what its makers hope is a turning point in the way challenges to the environment are presented and reacted to.

“I wanted this film to be more about empowering individuals to create change. We can blame governments and corporations for obstructing needed change, but ultimately real change has to first occur with people,” Psihoyos says.

Discovery Channel trailed Racing Extinction with the usual hyperbole, but the hyperbole rang true: in various, interrelated ways – human-induced climate change, deforestation, the illegal trade in wildlife and more – people are eradicating species at such a rate that many scientists believe the sixth episode of mass extinction in Planet Earth’s history is upon us. Some say the planet stands to lose up to a half of all its species by the end of this century.

The fifth mass extinction took out the dinosaurs and marked the end of a geological era, the Mesozoic, and the start of the present era, the Cainozoic or Cenozoic – the name being derived from the Greek for “new life”. Geological eras are divided into periods, which are further divided into epochs. Officially we are now in the Holocene epoch of the Quaternary period, which started around 11,700 years ago, after the last ice age.

But an increasing number of scientists believe we should now talk of the Anthropocene, meaning an epoch when human actions have fundamentally reshaped the geology and ecosystems of the planet. The validity of the label and when such an epoch began are matters of debate. But a ruling by the International Union of Geological Sciences due later this year could mean the official adoption of the name.

Whether or not the name sticks, the natural balance of our planet has undergone massive changes during the age of man. Most of us recognise this to be true at some level or other, but the problem is that we are so beset by other global woes – economic uncertainty and inequality, demographic imbalances and terrorism – that the documentary might have been more cynically entitled Racing Ambivalence.

The sixth mass extinction is a grand scientific hypothesis which, like climate change, is so bewilderingly huge and complex that many people are unable to get any intellectual purchase on it and simply give up. Even if they accept that extinctions are happening, whether they believe the scientific assertions or not, the grand idea becomes just a trite phrase. Dire predictions of future realities, lacking certainty, pegged to timeframes of decades or more and subject to widely varying estimates, are easily lost in the background against much tinier, yet more sharply defined everyday struggles.

To make his film compelling and ultimately inspiring, Psihoyos needed change-makers – people that can show how individuals can grapple with seemingly Herculean problems by thinking about them differently. One of Psihoyos’s first recruits happened to live in his home town of Boulder, Colorado: underwater filmmaker and photographer, Shawn Heinrichs.

“Everyone talked about how important it was, but very few wanted to see it,” Heinrichs says of The Cove. “Louie said he’d rather create a film that everyone wants to see, an accessible film that makes people want to do something.”

While Psihoyos had been documenting the terrible fate of whales and dolphins in The Cove, Heinrichs had been working on shark-finning and the more recent trade in rays. This trade was fuelled by cynically manufactured demand for their gill rakers, bony filters that rays use to sieve small prey out of the water, which had been uncovered by two Hong Kong photographers, Paul Hilton and Alex Hofford.

Psihoyos was shown the trade in China. “It really had a profound effect,” Heinrichs says. “He knew how bad things are in a small area, but with us he saw first-hand the massive scale of the trade. Certain parts of the world are just vacuuming up parts of the natural world.”

This story just had to be in the film, so the Racing Extinction crew followed Heinrichs and Hilton to get fly-on-the-wall footage as they pursued an ultimately successful effort to have manta rays included in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, or CITES, the appendix being a list of species that may become extinct if the trade in them is not closely controlled.

The inclusion helped them to stop the inhabitants of one village in Indonesia killing mantas and other rays to meet demand in China. The villagers are now being taught a more sustainable way of making a living by taking divers to see the fish they once would have killed for a one-off gain.

This victory is a turning point in the film, as it shifts from bleakly exposing the damage humans have been doing to hopefully suggesting how people might yet make amends. “If you keep feeding people shame and guilt,” Heinrichs says, “they become numb, and then they want to avoid it.”

Hence the change in tack. “There’s a lot of beauty footage in Racing Extinction. We give you real stories of real hope,” Heinrichs says. “The key is to make it accessible to the mainstream, focus on inspiration, reach a different audience.”

More hope comes in the form of technology. While humans have often proved to be myopically poor curators of the Earth and its other inhabitants, people are also endlessly innovative – and none more so than another of Psihoyos’s change-makers in the film, entrepreneur and innovator Elon Musk.

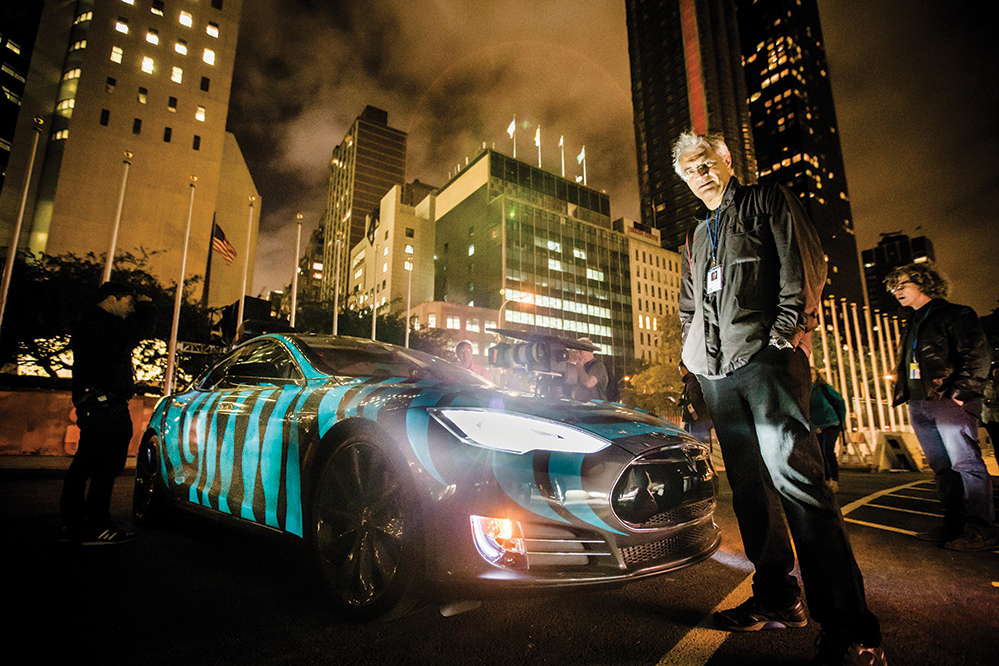

The man behind SpaceX’s reusable spacecraft, Powerwall next-generation battery technology and Tesla electric cars, Musk was happy to offer a new Tesla Model S to be turned into a stealth cinema on wheels.

A team led by Travis Threlkel of Obscura Digital tricked the Tesla out with projectors and speakers, and dubbed the resulting contraption Projecting Change. “Travis is a mad genius. He’s fearless and incredibly imaginative,” says Psihoyos.

Obscura Digital fitted a 15,000-lumen projector system to throw enormous images of endangered and extinct species onto important landmarks. A manta ray 40 storeys high sailed serenely across the face of the Empire State Building and jellyfish bobbed across the façade of the Vatican. Other images were beamed onto objects of opprobrium such as buildings belonging to Shell.

Specialists in electro-luminescence Darkside Scientific applied a paint job that allowed the car to be garishly visible or to go dark, as required, when a current was passed through it – a function inspired by bioluminescent organisms that use a similar stratagem. A specially filtered forward-looking infrared camera was set up to pop up out of the bonnet and make carbon dioxide and methane emissions from factories, vehicles and animals visible to the human eye.

To take Projecting Change on a global mission, they needed another change-maker. Enter racing driver Leilani Munter, a publicist’s dream with her looks and contrary record. Her website’s masthead reads: “Never underestimate a vegan hippie chick with a race car”. Munter has a degree in biology, has competed in the development leagues of NASCAR and IndyCar, and was in Sports Illustrated’s list of the world’s 10 best women racing drivers. She was also a great way to connect motor racing’s fan base with Racing Extinction’s message – as Heinrichs would say, reaching a different audience.

Ka-shing and the director of the Li Ka-shing Foundation, Solina Chau, were among those that helped send this show-on-wheels around the world. “Li Ka-shing and Solina Chau have been incredible ongoing supporters of the illuminations, which have been successful beyond comprehension,” says Psihoyos. “The projections on the Vatican received something like 4.5 billion media impressions. The Empire State Building projections became the top-trending story on Facebook and Twitter for four days worldwide. We have plans to do more events now on iconic structures all over the world.”

Racing Extinction had its premiere at the Sundance Festival in January last year, after which Psihoyos and his team clinched a worldwide distribution deal with Discovery Channel. “We went with them because they promised a huge audience, which they delivered,” Psihoyos says. Some 36 million people watched around the world on December 2 and since then many more have seen the film at authorised showings.

Once the audience is reached, the Racing Extinction website urges them to”StartWith1Thing” and then share it with the world. Examples on the page include signing a pledge against the trade in wildlife, eating no meat at one meal or calculating their carbon footprint. Links take the audience to the next step in each case – a pledge form, vegetarian recipes, a carbon calculator.

“The feedback has been massive compared to other things we’ve all done,” Heinrichs says, “Some of these storylines have been running for close to a decade. RE allowed us to amplify them on a global scale.”

That Racing Extinction was aired by Discovery Channel is something of a paradox, given that the channel was not the environment lobby’s favourite broadcaster. Heinrichs and many others objected to what they felt was the needlessly sensational portrayal of sharks by programmes during Discovery Channel’s annual Shark Week.

“For many years I refused,” says Heinrichs about being asked to contribute to Discovery Channel. But early last year, HBO veteran John Hoffman was made the channel’s executive vice-president of documentaries and specials. Just before joining Discovery Channel, Hoffman had been producing documentaries on health issues for his own non-profit concern. Heinrichs believes the appointment of Hoffman helped the channel “get back to their roots, get back to factual work”.

Discovery Channel persuaded Heinrichs to be one of its shark ambassadors later that year, telling him he could say what he believed. “So I can say I don’t like your shows?” he asked. “Absolutely,” came the answer. He knew then that the channel was serious about its new commitment, he says.

Racing Extinction underscores that commitment, and Heinrichs says the next step is to develop the partnership his campaign has established with Discovery Channel. “We’re moving towards materials for schools, support for further showings,” he says. “We don’t want to lose the momentum,” he says. “It’s about how we keep filling the pipeline.”

Youngsters are crucial, Heinrichs thinks. “We have more access to the young than ever before,” he says. “They are highly impressionable and more likely to reach their parents than we are.”

But Heinrichs believes people of all ages must be reached, and that the opportunity to do it must be seized now. “We don’t have time for the really young to grow up,” he says, “and teens don’t move the needle very much. We have to get to businesses and the older ones who control the wealth.”

“You’ve got to pick your fights,” says Hilton, speaking after photographing yet another shipment of wildlife confiscated in Indonesia. His latest fight is for the Leuser Ecosystem, 2.6 million hectares of tropical rainforest that spans almost the entire width of the island of Sumatra.

In a book entitled On the Edge: The State and Fate of the World’s Tropical Rainforests, a former director-general of WWF International, Claude Martin, writes about “fatal interactions between deforestation, forest fragmentation and climate change”.

Martin describes how these interactions threaten to destroy what remains of the rainforests. The forests are being hollowed out so that even where they cling on, they are diminished in their ability to support the full web of life. Crucial species of trees are logged out, and populations of animals are poached or so reduced in their distribution that they cease to be viable.

“The Leuser Ecosystem still has viable populations of Sumatran tiger, elephant, rhino, orangutan – but they want to open it up to palm oil,” says Hilton, “It’s getting to crunch time. We’re down to tens and hundreds of these animals.”

Most people are aware of the plight of the Amazon rainforest, which at times has been taken as representative of all tropical rainforests. But today it is in Asia that the pressure to clear land for palm oil plantations and other forms of farming is most insistent and threatening. Indonesia is one of the world’s greatest emitters of greenhouse gases, mainly because of the deforestation of its land. Much of the deforestation is illegal, yet it seems to be beyond the government’s control.

The Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation gave US$3.2 million to grassroots groups in Indonesia through the Rainforest Action Network last July. The money is meant to help create a megafauna sanctuary in the Leuser Ecosystem for those charismatic mammals. Hilton hopes DiCaprio is on board for the long run – long enough to drag this vital area into the world spotlight. “I want it to be known like a Yellowstone or Kakadu,” he says.

OPS has pitched in, making a video about the destruction of the Leuser Ecosystem for palm oil plantations and collecting names on a petition calling for the palm oil industry to stop its destructive practices.

“The film gave us an avenue to inspire people across all walks of life,” Hilton says of Racing Extinction. “Louie called it ‘a weapon of mass construction’,” he says. “If everyone does something, then we’ve got a movement.”

In a TEDx event entitled Art Inspiring Action to Protect Our Oceans, held in his home town in 2013, Heinrichs demonstrated movement of a different kind in collaboration with Hannah Fraser, an activist on behalf of the oceans who specialises in underwater performances.

In closing his presentation, Heinrichs said: “I believe art is such an essential tool in halting the destruction of these threatened species. By connecting people with the beauty and vulnerability of these animals, we ignite a new level of curiosity and passion for them, because ultimately it is the human connection that is central to conservation. Without it, our efforts will ultimately falter, but by harnessing it, we can change the world.”