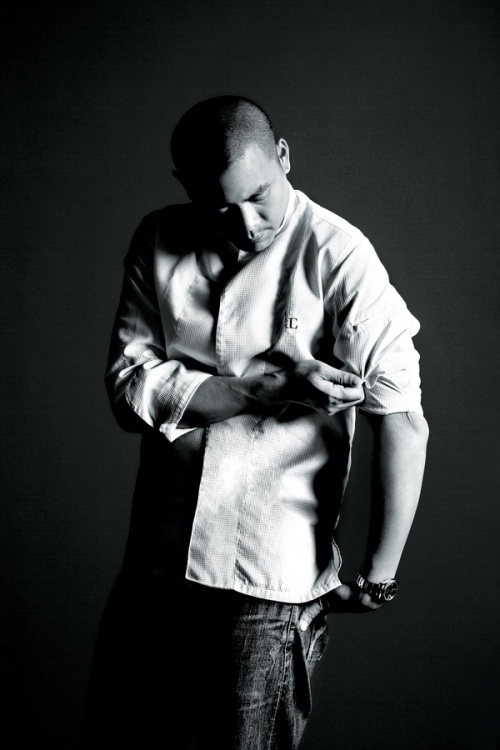

The word is big, but the meaning is quite simple, according to Chef André Chiang. The word is “Octaphilosophy”. It is the title of a book by Chiang published by Phaidon, which he’s in Hong Kong to promote. It is also the name of the culinary concept Chiang puts to work in the kitchen at his eponymous Restaurant André, in Singapore. Octaphilosophy is also the key to appreciating his eight-course degustation menu.

“It’s not rocket science, not too complicated,” Chiang says, producing several pieces of wax paper inscribed with geometrical shapes, each representing a dish. “What we did was analyse every dish to give it its DNA. Ideally, if the eight dishes are balanced, then all of them, put together, form a complete octagon.” He puts the pieces of wax paper together to demonstrate the point.

“Sometimes as a chef, we do something because we like it and then we realise that every dish is about one thing,” Chiang says. “Maybe it’s about texture, and the next dish is about texture, and the third course is about texture. Our palate gets tired of the same thing after the third course, if you constantly repeat the same concept. So to hit the different sides of your brain, this is what we did.”

The eight key words in Chiang’s kitchen are: pure, salt, artisan, south, texture, unique, memoir and terroir. Sit down for a meal in Restaurant André, and instead of a menu describing the dishes you’ll be sampling, you’ll be handed a list of the eight words, with brief explanations of what each means.

“The artisan dish is one that doesn’t belong to me. It belongs to the artisans, the corn farmer, and what he thinks is the best way to eat it,” Chiang says, by way of illustration. “And then we try to replicate that in the dish.” The pure dish relies on the quality of the main ingredient. “We do not use seasoning or electricity or gas when we prepare a pure dish,” the chef says.

Chiang is from Taiwan, but left the island when he was aged 13 to work with his mother in Japan. She was running a Chinese restaurant there and had hoped he would one day take over. At the age of 15 he felt the urge to learn something new and so went to France, where he worked under the brothers Jacques and Laurent Pourcel at Le Jardin des Sens Montpellier. Chiang calls these luminaries of French cuisine his first teachers.

“In my mum’s kitchen, she didn’t allow me to have any creativity. All Chinese kitchens are like this,” Chiang says. “You learn the technique: this is how to make things crispy, this is what sweet-and-sour is supposed to taste like. But you’re not allowed to be creative. My mum would say, ‘Don’t try to be funny. You do what I tell you.’ But when I went to France, it was totally the opposite.”

With the Pourcel brothers, Chiang learned to work with humble ingredients, turning humdrum potatoes, tomatoes and onions into something extraordinary. Later, working with chefs that included Michel Troisgros, he learned other things: control, using only five ingredients and techniques a plate. In his work with Pierre Gagnaire, he learned to think outside the box and not be defined by rules. With Pascal Barbot, he learned to run a Michelin-starred restaurant with a staff of three people. At that point, Chiang felt he could open his own restaurant.

When he turned 30, Chiang left France to set up his first restaurant – in Singapore, which he felt, had culinary potential. “Ten years ago Singapore wanted to have everything everyone else had,” Chiang says, reeling off names of famous restaurants that had incarnations in the city. “But in the past five, six years, they started to change. They wanted to have things that other people didn’t have.”

When Chiang opened Restaurant André, he wanted to create his own cuisine – neither French with an Asian twist, nor just French cooked by an Asian. Chiang knew he could do it, because he had done it before, having created the first dish he could call his own in 1997, when he was in France. He tells the tale in his book.

“The Pourcel brothers asked the whole team to be creative and invent new courses,” Chiang writes. “Of course, this game became a competition. We were 25 chefs, and well aware that if any of our courses were approved by the brothers, it would be put on the menu.” Chiang was the only Asian in the kitchen, but was disinclined to create an Asian dish. So he chose to make what he describes as “something delicious that exuded the spirit of France”. It was a warm foie gras jelly with Périgord black truffle coulis. The Pourcel brothers approved the dish and added it to the menu the next day.

“I don’t think I have ever been so proud,” Chiang writes. “It was confirmation that I had made the right choice and that I belonged there, in that particular kitchen, working with my mentors Laurent and Jacques Pourcel.” In octaphilosophy, the dish is now a memoir item, served in Restaurant André.

Chiang says that each time he makes the dish, it takes him back to where it all started. It was served on Chiang’s visit to Hong Kong as he got together with Chef Richard Ekkebus of Amber restaurant in the Landmark Mandarin Oriental hotel to show what they can do as a team.

“I gave André the first pick of which dishes he wanted to serve and I worked around his menu to make sure there was a balance,” says Ekkebus. Among the other results of their collaboration was the return of Amber’s famed foie gras and raspberry lollipops, and a cake made by Chiang that is considered another memoir dish by the school of octaphilosophy.

Chiang and Ekkebus both worked under Gagnaire but at different times. Ekkebus believes the French luminary taught him an important lesson in the four years he worked under the chef. “It was Pierre Gagnaire who started this movement of saying, you don’t need to use the centre of the plate, you can use the sides of the plate. He broke a lot of barriers of how food was perceived,” he says.

“I always call him the jazz musician, because he plays without partition,” Ekkebus says. “When he plays, he just plays and he will change the song in any way and shape he likes.” Says Chiang: “He shows you one thing, and then he goes out to see the guests, and he’ll come back and say, ‘André, why are you doing this?’ And he’ll change it.”