British artist Charles Sandison, a pioneer in merging language, code and light, invites dionne bel into his world of living algorithms and digital prophecy with his latest AI-driven installation on the mountainside in Delphi, Greece

Long before ai entered the global zeitgeist, Charles Sandison was quietly writing its poetry. Born in rural Northumberland and raised in the windswept Scottish Highlands, the British artist taught himself to code at just 12 years old – decades before

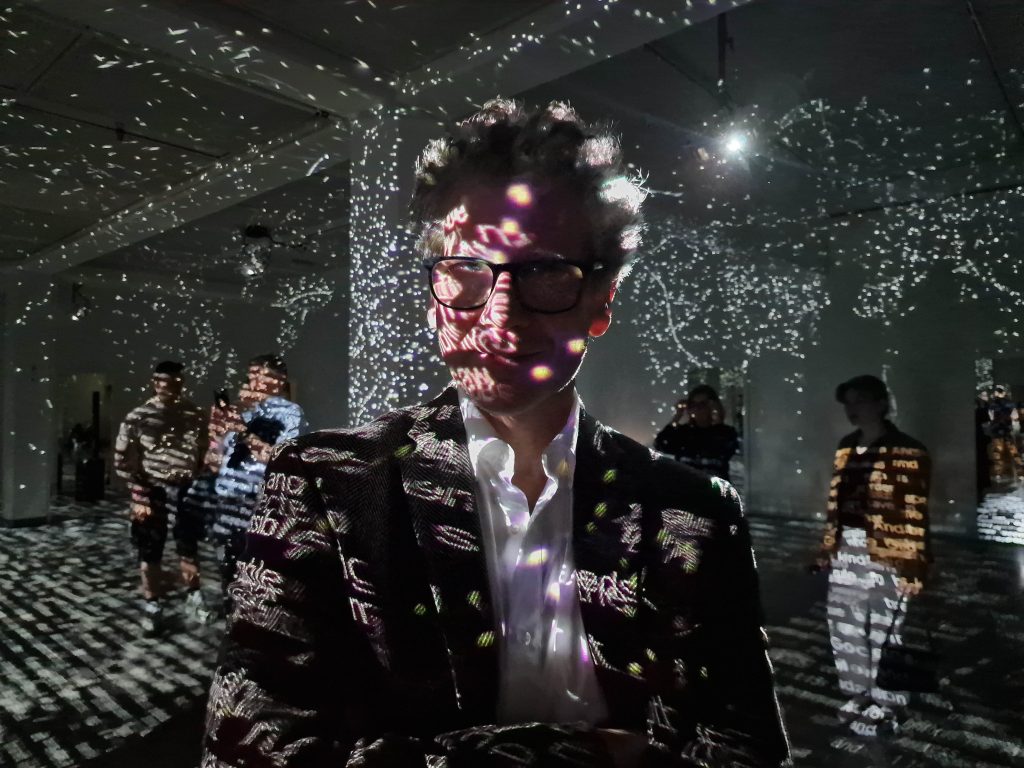

personal computers became household staples. That early fascination with programming laid the foundation for a groundbreaking artistic language that fuses words, symbols and algorithms into immersive environments. Sandison doesn’t just use code as a tool; he sculpts with it, orchestrating luminous swarms of text that move, evolve and respond like living systems. His work is a hypnotic blend of language and light, where digital projections spill across architectural spaces, ancient ruins and vibrant gardens, exploring the primal human impulse to communicate, record and divine meaning from the chaos.

Sandison’s latest and most ambitious installation, The Garden of Pythia, commissioned by the Polygreen Culture & Art Initiative (PCAI) – an organisation merging culture and ecology founded by Athanasios Polychronopoulos – was unveiled last April at Pi, the Global Centre for Circular Economy and Culture in Delphi, Greece. Inspired by the famed Oracle of Delphi of the Temple of Apollo, the work draws a striking parallel between the prophetic rituals of antiquity and today’s

machine-driven quests for knowledge. Using AI-coded software and real-time environmental sensors, Sandison transforms the garden into a responsive organism – an ever-shifting constellation of historical texts, Delphic statues, mythic symbols and local ecological data projected onto the landscape. It’s a poetic convergence of past and future, where Mount Parnassus meets his computer’s silicon matrix. “The answers we seek from AI,” he says, “are the same as we asked from Pythia.” With this artwork, he not only bridges centuries of human inquiry but reminds us that even in the age of algorithms, we’re still guided by the same ancient desire: to ask, to know and to wonder.

You taught yourself to code at a young age – how did that shape your artistic language?

My best friend growing up from the age of 12 until I went to art school was a little Sinclair ZX81 computer, and I taught myself to code. At the same time, I was drawing and painting. That was my primary way of speaking to the world as a kid. Later, I realised that painting, drawing and writing computer code are kind of the same thing for me.

You’ve spoken about having dyslexia. Did that influence your focus on language in your art?

I couldn’t read until I was about eight years old. Language has always been mystical, powerful and strange to me. Words had shapes. Some words were angry words. It wasn’t about meaning – it was structural. I started thinking of language as a biological organism, like cells bumping into each other, passing on DNA.

How do you see the relationship between technology and art?

I don’t see a difference. The Greek word techne means to create. Tools are a form of language. They’re how we leave our marks across generations. I think we’re not just using language – we are language.

The Garden of Pythia uses AI more than any of your previous works. How so?

This is probably the strongest use of code-writing AI in my career. I write my own code in C++, but now I can say to AI:

“I’ve got these variables, can you conjugate the code?” And it will do it. It’s like I’ve grown a new muscle in my brain – it’s become an extension of my thought process.

The installation draws a parallel between AI and the Oracle of Delphi – can you explain that?

The Oracle was the first AI in a sense. It was a kind of machine intelligence – or a biomythic intelligence – artificial, nonetheless. People brought questions, and answers came from behind a screen. That’s exactly how we treat AI today.

How does working in situ affect your process?

When I’m on site, that’s when the real connection happens. I work with light. My installations are generative – constantly changing. I don’t just plonk the artwork down; it’s a performance, like a dance with the place. I let it influence me. I have to move things, make creative decisions and adapt the idea to the environment. I vowed that it was more important that I could react in the moment, that if something’s broken or doesn’t work, then I could accept it and still discover something new

even if the vision I had in the studio didn’t match the practical vision of the final two or three weeks of intense on-site creation when I install the work.

What’s your role as an artist in this increasingly algorithmic world?

I feel like my job isn’t to show something new – that would be terrifying, if an artist actually put something that nobody understood. I use projection because it’s not like putting stuff onto a screen; it’s actually acting like a flashlight, revealing what’s already there that we can’t see with our eyes. It’s like putting on X-ray glasses and then we can see. A lot of our consciousness is not necessarily about trying to become wiser and to understand more; it’s actually trying to narrow down all of the information.

Also see: Photographer Sebastião Salgado on his visual poetry