As colouring pencils have become his trademark, English artist Luke Newton is convinced that the pen(cil) is mightier than the sword. He speaks to Dionne Bel about adding a dose of humour and cheekiness to his keen observations of contemporary society to make us see the bigger picture

Imagine a well-stocked armoury replete with a Thompson submachine gun, Smith & Wesson revolver, Glock, M16 rifle, Remington 870 shotgun, MG 3 machine gun, Colt handgun, suicide vest and dynamite. But these aren’t ordinary weapons – they’re made from thousands of stacked colouring pencils in an array of vivid shades, enticing us to play with them.

Neither firearms nor children’s toys, these assembled drawing instruments have been stripped of their functionality and reduced to useless tools, transformed into sculptures that have become Luke Newton’s signature works ever since the 2015 terrorist attacks on the Charlie Hebdo satirical newspaper in Paris left 12 dead. Pencils embodying the power of creation and imagination became symbols of resistance and freedom of expression in France, and through his pieces in which violence and innocence converge, he unites what initially appears to be diametrically opposed.

A technique encompassing repetition, precision and patience, there’s no room for error. Once Newton has glued the pencils together, it’s impossible to backtrack and undo what has been done. He would have no choice but to start again. Making painstaking work look easy, his sculptures’ slick, clinical aesthetic belies the complexity, time and energy demanded for their construction, as each new piece is a long-term undertaking, taking up to one month to build.

The rocket launcher comprises approximately 2,500 pencils, while the skull required 1,500 pencils and three weeks of 12-hour days to produce, excluding the planning and design stages and the construction of the first prototype. Sometimes he’ll make a sculpture 10 times before he’s satisfied with it in a process he qualifies as “between meditation and masochism”.

Underscoring the contradictions inherent in each one of us and in the world around us, Newton asks viewers to contemplate the meaning of commonplace objects that populate our consumer society, subverting their symbolic value in a mischievous manner. Tackling the issues and absurdities ailing contemporary society in a way that we can relate to, he defuses the situation and offers a fresh perspective. His Happy Valentine’s axes, Heart Target series and a guillotine entitled Killing Me Softly, whose angled blade has been replaced by a sharpened heart, interrogate the symbolism of the heart and explore its duality in which love and pain inevitably coexist.

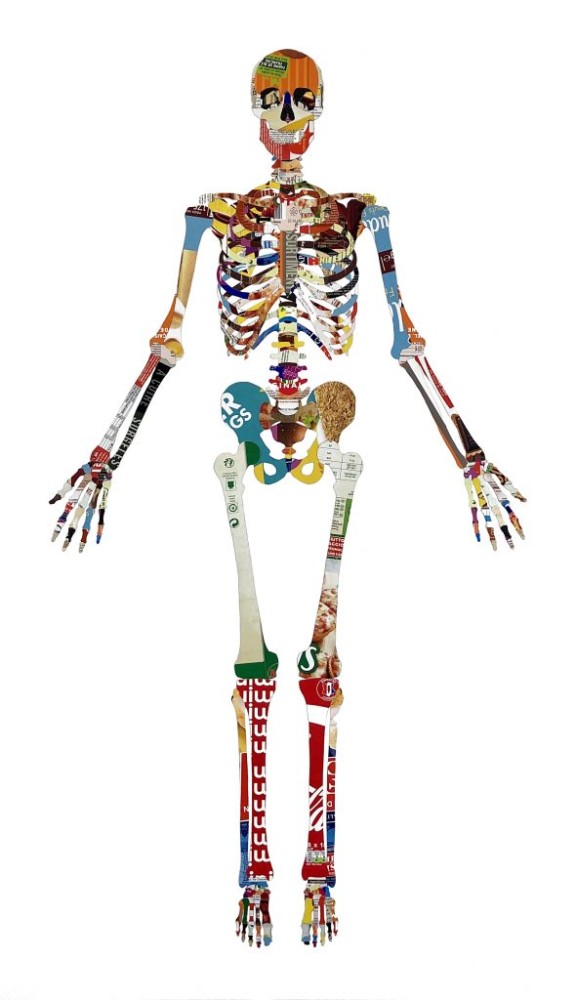

He crafts skull and skeleton collages from upcycled food and medicine packaging that he repurposed during the Covid-19 pandemic to suggest “we are what we consume”, converts hashtag signs into wood or concrete sculptures to retreat from the digital space, and paints the LOL acronym ubiquitous on social media as reinterpretations of Robert Indiana’s iconic 1960’s Love pop art masterpiece, which has been subject to so many authorised and unauthorised reproductions that it has lost all meaning.

Also see: Fashion Shoot: Sense of identity

Born in 1987 in Burnley in northwestern England and raised in Colne, Newton graduated with a BFA from Central Saint Martins in London in 2008. Living in Paris since 2010, he splits his time today between the capital and Roubaix, a northern French city once reputed for its textile industry that reminds him of the cotton mill towns of his childhood. For A Consumer Product, his first solo museum exhibition in France currently showing at La Piscine in Roubaix until January 8, 2023 that he calls “a massive honour to be invited to exhibit there”, he’s presenting close to 80 pieces, mainly new sculptures and collages. He says, “It’s a social commentary from my point of view, but I want people to enjoy the works and hopefully they’re accessible for everybody.”

A solo show with Newton as guest of honour of an annual art salon at L’Etoile cultural centre in the neighbouring city of Mouvaux will take place concurrently from November 18 to 27, 2022, alongside the presentation of Like Me, Like You, his white knight in armoured steel proffering a red heart, at Château d’Hardelot located between the forest and the sea in northern France.

When did you know you wanted to be an artist?

I don’t know whether I made a conscious decision to become an artist because I’ve always made art – it was my way of expressing myself and communicating. Today, I’m lucky that I can make art my job, but making money from art was never really the motivation, just the ability to make art. My uncle, Mark Newton, was a massive inspiration growing up. He was kind of the first rebel of the family because he was always interested in art and painting and was the first to move away from the north of England.

He inspired me to see the bigger picture outside of my hometown and showed me a way to express my creativity and was always super supportive of that. As he was very involved in the art world, he opened a lot of doors. He was good friends with the gallerist Anthony Phuong, who offered me my first solo exhibition in 2011, and he told me that the artist JonOne was looking for an assistant – I ended up working with John for 10 years.

Describe your artistic language and philosophy.

It’s important that my work be accessible to different audiences, young or old, and that it doesn’t become some elitist notion of art. And that it has a concept behind it, that it’s saying something other than just its own existence, that it has a message or a story to tell, a different way of thinking about everyday life that hopefully people can read into, analyse and make their own judgements.

I think life is very paradoxical in nature, so I try to make my work about the everyday and highlight those paradoxes. The common idea behind my work is the observation of the world in which we live. Another theme is flipping concepts or social commentary, but it’s not criticism – I don’t want to preach in my work.

How did you come up with the idea to use colouring pencils?

Futility is something that has always interested me, the idea of art being futile and existing within itself. One series that I was making was a homage to Marcel Duchamp and the readymade object and the beauty that the readymade object has within itself, so I was assembling pencils together, which made the tool itself useless, but it helped you see the beauty of everyday things and question their functionality or practicality, what constitutes art.

At the same time, I was making silhouette paintings of weapons because I was trying to make a social comment on the commodification of objects in society and the commodification of art by giving people the possibility to buy their weapon silhouette in whatever colour they desired. I decided to join the two ideas together and make weapons out of the pencils themselves.

When David Pluskwa gallery in Marseille asked me to make a piece for an auction for the victims of the Charlie Hebdo terrorist attacks, it seemed like the right time to start this series that had been floating around in my head for a while, as pencils took on social symbolism as symbols of liberty, freedom of expression and creativity.

By making your sculptures colourful, you make your weapons appear joyful like toys that seduce viewers, whereas we’re always telling kids not to play with guns.

Exactly. What interests me is the subversion of the associated symbolism. We can imagine a child colouring or drawing with colouring pencils, so we already have a pre-formatted concept of what the material is used for, and then confronting it with a different symbol with which we associate aggression, death and violence. It creates this contrast between two pre-formatted concepts, and that space in between is what interests me.

Have you ever been tempted to go to the shooting range and test real guns?

No, the message behind my work at the end of the day is the opposite of the symbolism of a weapon itself. It’s more a symbol of peace and creativity than it is a symbol of destruction. These paradoxes are at the heart of my work, and my message is supposed to be generally positive, like the creative capacity of human beings or how a pencil can be stronger and more poignant than a gun. It’s about the duality of human beings, their creative and destructive nature.

What’s the idea behind your # series?

This series is an exploration into the way in which the world is becoming more and more digitalised. A hashtag is something that’s used to link to something else; it’s not an object in itself. But I wanted to make the hashtag be exactly what it was, what it was supposed to link to, so it would be a hashtag in concrete or in wood, a bunch of different materials. The hashtag becomes a physical object rather than just a digital representation or digital link to something. It’s a way of pulling back from this digital world in which we live and to bring more materiality, making things more physical.

Also see: #legendbeauty: All about Aesop’s Eidesis Eau de Parfum