Filmmaker-turned-artist Tsai Ming-Liang and long-time collaborator and actor Lee Kang-sheng explore the slow life in Footprints of the Walker: Tsai Ming-Liang. Jaz Kong reports

Some say meditation can be practiced anywhere, anytime – whether through traditional lotus or kneeling positions rooted in Buddhist and Hindu traditions, or simply through mindful breathing and each step we take. For Malaysian-born, Taiwan-based movie director Tsai Ming-liang – best known for his earlier feature films such as Goodbye, Dragon Inn and Vive L’Amour – “walking” has become a transformative act in both his career and personal life.

Moving fluidly between commercial cinema, arthouse films and even art museums, Tsai is an unorthodox filmmaker, a multifaceted artist and a devoted Buddhist. In his latest exhibition, Footprints of the Walker: Tsai Ming-liang, held at Taiwan’s Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts (KMFA), Tsai and co-curator Sing Song-Yong invited audiences into an immersive experience – one that evoked the quiet passage of time and the emptiness of our reality – through the detailed journey of the 10 films in Tsai’s Walker series.

The first collaboration between Tsai and the KMFA, the retrospective served as an alternative cinematic marathon across films of various lengths. The exhibition space, meanwhile, was designed not for passive viewing but for immersive disorientation. Visitors may have found themselves lost – physically and spiritually – as they stood in the middle of the room, surrounded by moving images and layers of sound (or the lack of), as if positioned at the centre of the world.

The experience evoked a sensation that Earth itself had been compressed into this one room, where multiple realities unfolded simultaneously, to the point where one’s very existence felt questionable. Tsai deliberately designed this part of the exhibition to echo the different facets of a diamond. He explains, “Standing in the middle of the room gives you an illusion of standing inside a diamond and you’re looking at its many facets, which is also an echo of the Diamond Sutra.”

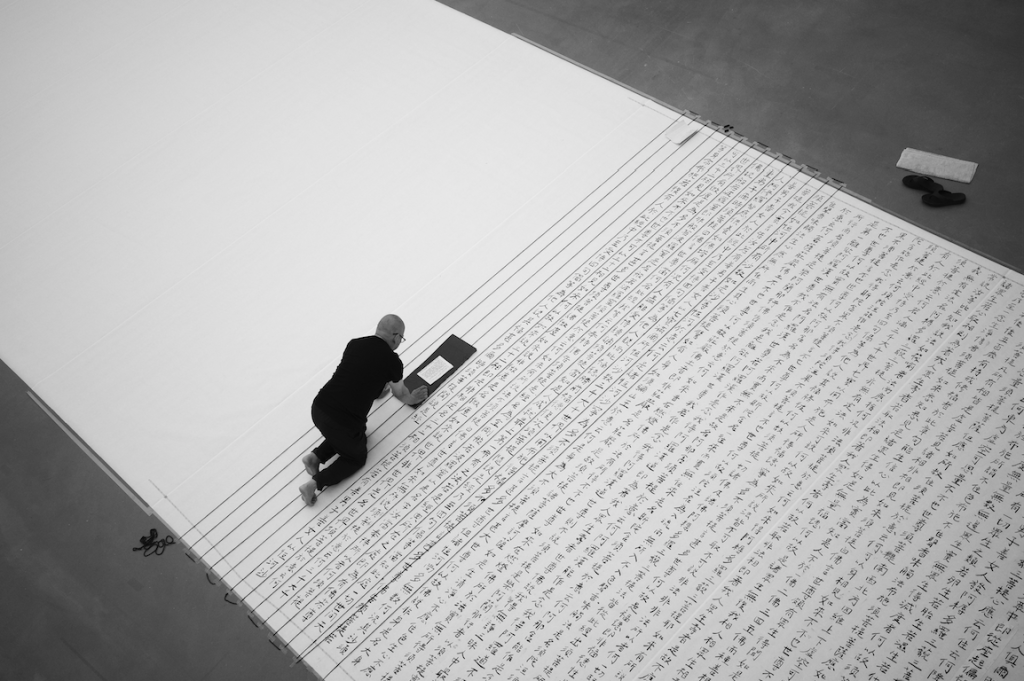

Beyond this sensory labyrinth, Tsai offered a gesture of quiet contemplation: a large, hand-copied version of the Diamond Sutra, which he transcribed over five days. His intent wasn’t to impose Buddhist philosophy, but rather to share the tranquillity through sacred texts. The sutra echoes the legendary journey of Xuanzang, the monk from ancient Chang’an who defied imperial decree and crossed treacherous landscapes in his 17-year quest for the Dharma in India – a pilgrimage both physical and spiritual.

The exhibition extended to include cinematic installations such as No No Sleep at MoNTUE, Walker, Tsai Ming-liang at the Zhuangwei Dune Visitor Center and A Quest at the Centre Pompidou. Displayed alongside paper scrolls, sutras, mirrors, sketches, chairs, paintings and archival materials, Tsai’s multi-screen installations cultivated a meditative visual environment. Light and shadow, colour and texture, missed encounters and fateful meetings, the finite and the infinite – all woven together to form the unique universe of the Walker.

Much like life itself, the best things often unfold unexpectedly. The 10 films in the Walker series were never part of a grand master plan. It all began 14 years ago, when Tsai directed a stage production titled Only You, featuring his long-time collaborator and actor Lee Kang-sheng. In the performance, Lee delivered a monologue titled The Fish of Lee Kang-sheng: The Journey in the Desert. A disagreement between Lee and Tsai led to a spontaneous decision that resulted in a perfect solution that left everyone in awe: Lee crossed the stage in a near 20-minute slow walk – one that unintentionally changed both Lee and Tsai’s lives for years to come.

The play was turned into a moving image production in 2012 when Tsai had a hunch. “I wanted to make a film about walking, so I did one in Taipei,” he recalls. “I had Lee wear red and shave his head. Monks don’t always wear red, but I personally love the colour. I was inspired by the reds in Malaysian artist Chang Fee Ming’s paintings of Tibetan lamas.”

Costume designer Wang Chia-hui helped bring Walker to life. Instead of cutting fabric into a conventional robe, she used a single length of hand-dyed cloth, held together with discreet pins. “He’s not a real monk,” Tsai explains. “The result wasn’t tied to any particular sect – it became a visual concept of the Walker.” In a conversation with co-curator Sing, Lee shared his own preparation process: “I go vegetarian while filming. When I’m in character, I don’t allow myself to speak or turn my head. Once I put on the robe, I feel a sense of responsibility.”

For Tsai, creation is not just a form of expression; it’s also a space for reflection. “Because of the Walker, I’ve been contemplating the true meaning of cinema.”

It began with a simple gesture of slow walking. While it may seem repetitive, that’s not the case. The Lee of today is not the Lee of two decades later. The world shifts every day. Walker represents a major shift for me – from directing fiction to non-fiction. However, it’s important to note that the Walker series is not a documentary. It’s non-fiction, yet non-documentary – a kind of new artistic expression.”

Walker also marks a spiritual transformation for Tsai – a path to spiritual liberation. “My filmmaking has moved away from traditional storytelling. I feel more like a painter now,” he says. “I only need a single tool to bring the film to life, and I feel happier and more at ease when filming the Walker. I still have other productions, but I now find greater freedom in what I do.”

For Tsai, the Walker series arrived at just the right moment in his life. “When I was younger, I had the strength, so I was able to make many films,” he reflects. “But from the beginning, my works have always been quite different. I’ve always focused more on self- expression. From Rebels of the Neon God to Vive L’Amour and The River, I’ve tried to convey my perspective on love, emotion and how I see the world.

“Now, I no longer have the physical stamina I had in my forties. And my feelings towards the world and humanity have changed. At every stage of life, I’ve been trying to communicate with the world. That’s why I want to offer the audience a sense of slowness – because the pace of my earlier world is so different from the one we live in today. I want people to know that such a world once existed – a slower era, with fewer people, less ugliness and fewer relentless pursuits.”

Also see: Hans Op de Beeck on ‘vanishing’ in his art

The Walker that was filmed in Hong Kong in 2012, especially the scene where Lee slowly walks through the busiest parts of Mong Kok, is a perfect contradiction of speed, purpose and aesthetics. “The reason I have to film a slow body is to have audiences focus on the world behind Lee, to observe the ‘status quo’ of our world,” Tsai says. “Take the Hong Kong version as an example – while Hong Kong cinema is famous for crime thrillers or romantic movies, we don’t really see Hong Kong in them. But it’s apparent in Walker – how people walk, what’s the sound of the area, what’s the vibe. I hope it can spark a reflection in people to re-think our ways of life. Is our world changing too fast? Why are we so busy and what exactly are we chasing?”

It’s perhaps the most poetic way to visualise the passing of time. While deeply artistic, Tsai believes the Walker series also carries a profound philosophical resonance. “Lee has a way of ‘restoring’ time,” Tsai explains. “When observing his slow pace, audiences often find themselves becoming aware of their own internal rhythm. Lee becomes an analogy for time.

He is living proof that time is passing – proof that this invisible element exists. Time comes and goes; and it stops for no one. But how do we choose to spend it? If we pause to rest, is that a waste of time – or is it an act of reclaiming authority over time?”

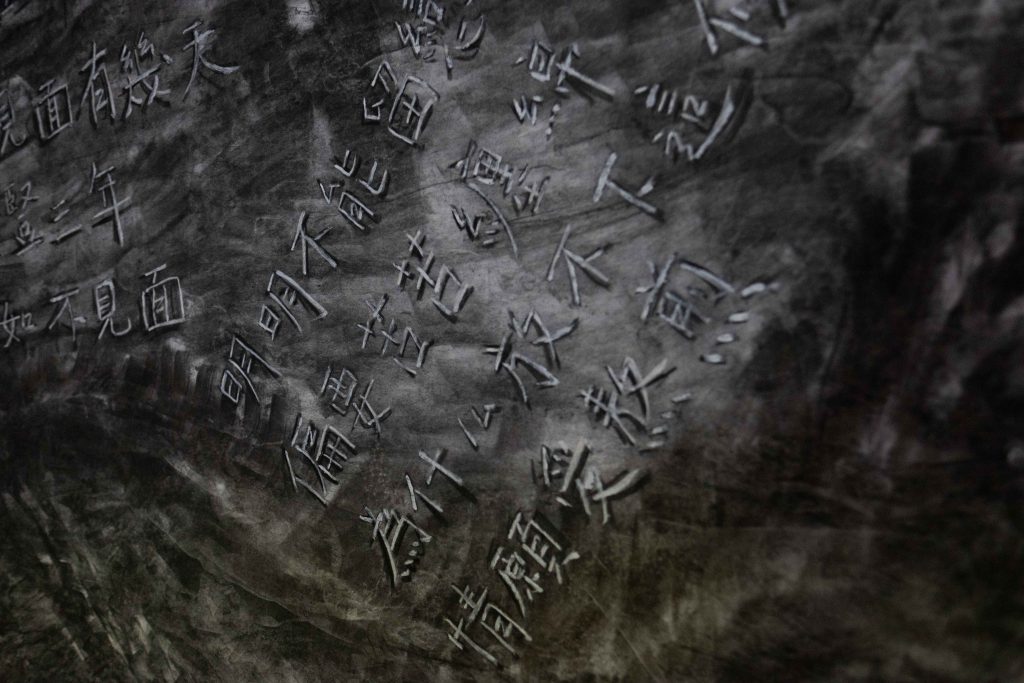

It’s perhaps for this reason that Tsai finds solace in the Diamond Sutra. According to interpretations, it emphasises the concept of śūnyatā (emptiness) and teaches that all phenomena lack intrinsic, independent existence. The term “diamond” symbolises wisdom that cuts through illusion, like a diamond slicing through anything. Audience members often remark that Lee, in his red robes, appears to idle somewhere between existence and non-existence.

Tsai responds, “Lee represents something many of us have forgotten – that it’s almost impossible to ‘own’ time. It’s intangible. It’s always moving. Our past, present and future are scrambled together, and we are only given so much of it. So are we truly choosing to live by social norms and fixed patterns? What else can we do, other than to work, sleep, love and stay ‘busy’ living – until we die? We must reflect on what has gone awry in our lives through slowness, and through the Walker films.”

A devout Buddhist for many years, Tsai began studying the Diamond Sutra in his forties, seeking solace during a dark period following the passing of his parents. “I calm my thoughts with sutras,” he says. “Both Buddhist scriptures and creative works are deeply intertwined with my life. The Walker character also embodies Buddhist values. I wanted to express something beautiful. But to truly feel the world as it is, one must slow down, like the Walker.” From the perspective of Buddhist philosophy, Tsai adds, “Even though the character may appear to be transcending the world, its nature is deeply engaged with it – much like a Bodhisattva, who chooses to remain in the world even after awakening.”

Tsai’s spiritual journey through Buddhism has profoundly reshaped the way he experiences life. What has inspired him most over the years is the Buddhist virtue of equanimity – the belief that all beings, no matter their form or scale, are equal, and that each has the potential to grow, evolve and eventually become a God. “I’ve slowly come to understand the world as belonging to all souls,” he reflects. “Souls and living organisms are diverse and equal, regardless of their size. That principle has been deeply instilled in me through the teachings.”

The Diamond Sutra, which records dialogues between the Buddha and his followers, often expresses truth in paradox: “The universe is not [real], but it is [merely] called the universe. Particles of dust – they are not, but are called particles of dust.” Tsai interprets this in more universal terms: “Everything is life. In time, your mind learns to let go of judgement and discrimination. Your heart softens. You begin to realise you’re not alone – that you live in a world that is diverse, beautiful and deeply good, a world we must protect and cherish.”

His decision to hand-transcribe the Diamond Sutra for the exhibition stemmed from a desire to share this calm. “Our conventional education teaches us to accumulate and to desire. But the Diamond Sutra teaches the opposite – it asks us to let go. These ‘things’ may seem like ours, but they never truly belong to us. When we leave this world, we leave with nothing. While the world urges us to chase, the sutra asks us to pause – to sit down and be still.”

Through the Buddha’s teachings, Tsai has discovered a sense of freedom – one that arises from turning inward, from finding clarity in the heart and mind, and from embracing stillness and slowness. “The Walker series is essentially about slowness, which is, in many ways, a form of rebellion in today’s world,” he reflects. “Our world has accelerated rapidly, especially in recent years, further reinforcing the idea that speed and efficiency are core values. With AI, computers, planes, everything moves faster. Our lives may appear more convenient and abundant. But is that truly the case? Have we paused to look inward, to ask whether the world is quietly exhausting us? Is greed slowly creeping into our lives?”

When an article feels too long, it’s now second nature to summarise it with AI – tools that are undeniably convenient. But perhaps it’s time we ask ourselves what we’re doing with the time we’ve saved. Is the time that’s been ‘freed’ by technology truly free?