Tudor splendour doesn’t come more splendid than Chatsworth House. Royalty, glamour, literature, art and a string of game-changing women have left their imprint on this illustrious and sometimes imperilled treasure. One of Britain’s best-loved stately homes, it is the seat of the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire, sits on a 14,160-hectare estate and is the livelihood of their 700 or more staff. Jane Austen wrote of it and Mary Queen of Scots was imprisoned there by Queen Elizabeth I. In more recent times Madonna has popped over for tea and Keira Knightley cavorted around its gardens in two films, Pride and Prejudice and The Duchess.

Two events this month commemorate one of Chatsworth’s most famous residents, Deborah Cavendish. Born in 1920, “Debo” was the youngest of the celebrated Mitford sisters. For half a century Debo was Duchess of Devonshire and the lady of the house, with a place at the centre of cultural and political life in Britain. She counted Winston Churchill, Harold McMillan, Evelyn Waugh, Prince Ali Khan, John F. Kennedy and members of the British royal family among her circle.

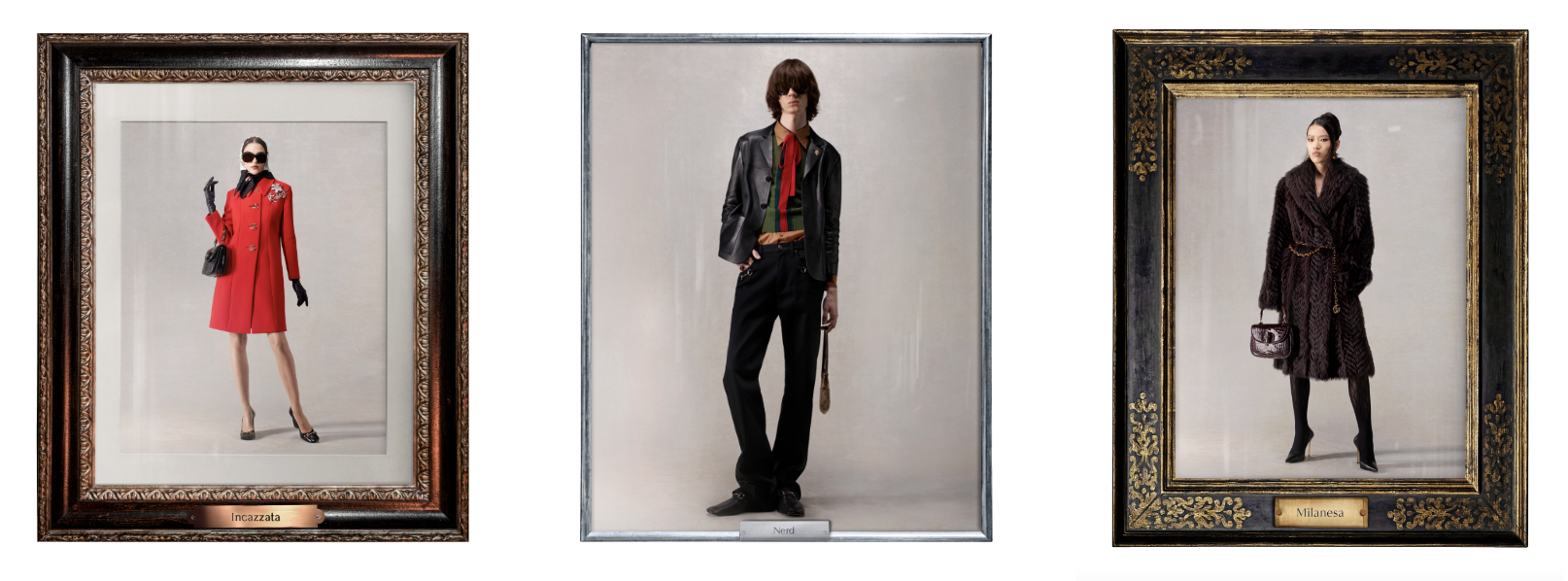

The duchess was dressed by Hubert de Givenchy, Oscar de la Renta, Balmain and Balenciaga, and photographed by Mario Testino, Bruce Weber and Cecil Beaton. Her supermodel granddaughter is Stella Tennant, whose Vogue magazine covers adorn the staircases of Chatsworth House. Glamorous to the last, in 2010 Debo was the subject of a 10-page Vogue special shot by Testino that featured Tennant and a brood of beloved chickens.

Debo was an instinctive entrepreneur. When she and her husband, Andrew Cavendish, Duke of Devonshire, moved into Chatsworth in 1959, they inherited crippling debts in the millions of pounds. The couple began selling art and coming up with moneymaking schemes, which 40 years later resulted in the Chatsworth estate standing on its own feet financially. The duchess opened a farm shop in 1976 and by 2004 it was making £5 million a year. The house is now one of the 10 most visited places in Britain.

Debo’s son, Peregrine Cavendish, known as Stoker, said of the efforts his parents made: “Thanks to their energy, imagination, and a healthy dose of stubbornness over a tenure of 50 years, they turned a sad and decrepit old place into a destination which three quarters of a million people enjoy visiting every year.”

Debo was a patron of the arts, author, countrywoman and, most famously, a great enthusiast for poultry. When de la Renta once came to dinner, the centrepiece of the table comprised glass boxes in which the duchess’ hens and chicks nestled. Debo spent the last 10 years of her life at The Old Vicarage, a charming 18th-century house in Edensor, a village on the Chatsworth estate. She died in 2014.

One of this month’s events is a sale by Sotheby’s of some of the late duchess’ personal belongings, in an auction entitled Deborah, Duchess of Devonshire, the last of the Mitford Sisters and Chatelaine of Chatsworth. More than 450 lots will go under the hammer.

They include jewellery and watches by Cartier and Breguet, and myriad brooches fashioned from gold, diamonds and other stones to look like butterflies, beetles, spiders or caterpillars. Also being sold are two sketches by Jacob Epstein, works by painter Lucian Freud, the duchess’ quirky Elvis Presley collection, and a brass novelty inkwell in the form of a lobster from 1890. And among the lots are some testaments to her eccentricity: a pair of monogrammed travelling boxes for poultry and a chicken-shaped powder compact.

This month’s other event is an exhibition of photographs entitled Never a Bore: Deborah Devonshire and Her Set by Cecil Beaton. On show will be rarely seen images of Debo and her dazzling social circle taken by Beaton. The photographer was a friend of the duchess and one of her first guests at Chatsworth, in 1959. Many of his subjects, including politicians, artists and Hollywood legends, were also guests at the house.

Beaton captured the 20th century’s most interesting personalities with his camera. A stand out is a picture of Fred Astaire, on a sofa, taken in 1931. Astaire’s sister, Adele, married Lord Charles Cavendish, the second son of the ninth duke. There’s also an image of Freud the painter. The exhibition runs until January next year.

Another lady of the house that left her mark there was Georgiana Spencer Cavendish, a member of the Spencer family who married into the Cavendish family in the 18th century and became Duchess of Devonshire. The duchess was painted by Gainsborough (whose portrait of her is still captivating), by Sir Joshua Reynolds and by Maria Cosway, who depicted her as the goddess Diana.

The duchess wrote a semi-autobiographical book, The Sylph, in 1778. She was subject of the film, The Duchess, in which she was played by Keira Knightley. The film was promoted as a tale of “sex, gambling, politics, love and deception – lived out for real in the 18th century”.

The present Duke of Devonshire says of his ancestor: “She was a woman of huge charm, attraction and interest. A compulsive gambler, she was also very political, and part of a society that revolved around parties and the politics that was done there.”

Knightley was allowed to look through a collection of the duchess’ belongings at Chatsworth. Knightley says she was shown letters, jewellery, paintings and notes from Georgiana’s creditors which showed how much debt she was in. “When she died she had been terrified of disclosing to her husband the amount she owed because she was convinced he was going to divorce her or send her away. There’s something incredibly sad about her,” says Knightley. “I think she’s a victim of herself, of her own innocence.”

No such thing could be said of at the remarkable Bess of Hardwick, the founder of Chatsworth. Despite the house’s grandeur today, the original Baroque structure, thought to be the work of Thomas Archer, was built for farmer’s daughter Bess, lady-in-waiting to Lady Zouche, who was in the household of Anne Boleyn, the second of King Henry VIII’s six wives. Bess was one of those 16th-century Englishwomen that exploited every opportunity to grasp power and wealth – another being Boleyn’s daughter, who became Queen Elizabeth I.

Bess scaled the social ladder to become the progenitor of a noble dynasty. She survived four husbands, each higher in status than the last. Her first husband died young, when she was 16. Then she married Sir William Cavendish – the king’s treasurer, who had benefited financially from Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries – and so became Lady Cavendish. Bess persuaded Sir William to buy land in the Chatsworth district of Derbyshire. On this land Chatsworth House was to rise. When Sir William died, his money passed to 30-year-old Bess and the land to their eight children. During their 10 years of marriage, England had four sovereigns: Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary I and Elizabeth I.

Bess’s third husband was Sir William St Loe, captain of the queen’s Yeomen of the Guard – what today we would call her security chief. They married soon after Elizabeth I ascended to the throne. The queen chose Bess’s wedding day – August 27, 1559 – and may even have attended the wedding. Six years later, Sir William died and Bess inherited his worldly wealth. Next she married the supremely powerful Earl of Shrewsbury, becoming the Countess of Shrewsbury.

Chatsworth was Bess’s life’s work. The building of the house spanned three of her marriages. In writing, the Earl of Shrewsbury affectionately addressed his wife by the name of her property, calling her “my honest swete Chatsworthe”. From the 1550s onward she directed the management of the house and how it was fitted out and furnished.

But Bess’s devotion to the task took its toll. By 1577, the earl was lamenting “how often I have curced the building at Chatsworthe for want of her companye.” When the earl died in 1590, Bess was 63 and the second-richest woman in England.

Bess began building another house, Hardwick Hall, which was completed in 1597 and moved into. She never saw Chatsworth House completed. The house is not all she left England: the current second-in-line to the throne, Prince William, is descended from her on both sides of his family. When Debo’s husband, the 11th Duke of Devonshire, died in 2004 and her son, Stoker, succeeded to the title, the dowager duchess moved out of Chatsworth, her home for more than half of her life, and settled in the Old Vicarage in Edensor. She wrote of the move in a book – Home to Roost, published in 2006 – that one of the luxuries of living in Chatsworth was never having to look “at anything ugly, because you were surrounded by the best of everything from four centuries”.

Chatsworth is renowned for its landscape, hospitality and art. The house has evolved to reflect the tastes, passions and interests of succeeding generations. Today, it contains works of art spanning 4,000 years, from ancient Egyptian and Roman sculpture; to masterpieces of painting by Rembrandt, Reynolds and Veronese; to work by outstanding modern artists including Freud, Edmund de Waal and David Nash.

There is art in the famous garden, too, which boasts sculpture by Lynn Chadwick, the British artist whose work will go on public display in Hong Kong later this month. Some new sculpture by Henry Moore will arrive at Chatsworth in the course of this year.

Chatsworth has a long association with the literary world. The house is reputed to be the model for the fictional Pemberley, the residence of Mr Darcy in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice.

“The eye was instantly caught by Pemberley House,” wrote Austen. “It was a large, handsome, stone building standing well on rising ground, and backed by a ridge of high woody hills; and in front, a stream of some natural importance was swelled into greater, but without any artificial appearance. Its banks were neither formal, nor falsely adorned.” The novel mentions Chatsworth in its own right as one of the places Elizabeth Bennet visits before arriving at Pemberley.

The present Duke of Devonshire owns the antiquarian bookshop called Heywood Hill, in London’s Mayfair district, where his aunt, Nancy Mitford, author of Love in a Cold Climate, worked during the Second World War. His mother, Debo, was also a successful author, having over a dozen books published, including Wait for Me and Tearing Haste.

One of the lots at the Sotheby’s auction is a pre-publication copy of Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited, in which the author invites suggestions and revisions. It is signed by Waugh, with the inscription: “Debo & Andrew/ with love from/ Evelyn/ A very old-fashioned story”.

Writing many years later, the duchess observed: “In spite of his uncertain ways, Evelyn remained a friend and a generous one…He sent us the limited edition of Brideshead in its floppy, dark blue cover.” It is estimated that the book will fetch up to £20,000.

Also being auctioned are books inscribed by members of the Kennedy family, attesting to the duchess’ long friendship with the American dynasty. Her brother-in-law, Billy, married Kathleen “Kick” Kennedy, sister of JFK, and through her Debo formed a close relationship with the president and his siblings. JFK danced with Debo at her coming-out-ball. Another lot is a copy of Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking, published in 2006, bearing the inscription: “For the Duchess, I hope this book inspires you as much as it inspired me! Thanks for your hospitality. All the best, Madonna”. The Material Girl gave the book to her kindred spirit when she visited the old vicarage in 2007.

“Madonna visited incognito and stayed with the duchess for two days,” says Chatsworth’s head housekeeper, Janet Bitton.

“She was making a film about Wallis Simpson and Edward, and the Duchess was the only person still living who had known all the people involved and socialised with them.”

Bitton says the library is a big draw for all visitors to the house.

“The favourite room is the library. We have documents that go back to the times before the printing presses, made from vellum. The sixth duke used to buy libraries.

In recent times, we have a first-edition Harry Potter there, signed by J.K. Rowling. She came and gave it to the 11th duke. In fact, as I turn to my right, there’s a broomstick over my head from J.K. Rowling and she’s written above it, The Fire Bolt.”

The head housekeeper finds it hard to decide which is her favourite piece of Chatsworth treasure. “I think, for such a vast place, I keep seeing things I haven’t seen before. I remember my first year. I went to the private side and saw the family’s private paintings, and how gorgeous they were. And so it goes on.

“My last memory was setting up scaffolding on the great stairs during the winter to clean the statues. Being up there and so close to things which hadn’t been cleaned for decades was fabulous. That’s why it’s a lovely place to work, because there are memories like that all the time. You never know what it will be next. It is like a dream to work here.”

And the place is a dream to visit. The hoi polloi cannot stay in Chatsworth House, but ordinary mortals can spend the night at one of the cottages on the estate. If you have a penchant for things equine, visit in May, during the globally renowned, Bentley-sponsored International Horse Trials, when sightings of Princess Anne are common.

The pick of the estate – beating the Russian cottage, inspired by Tsar Nicholas’s gift to the duke in 1855 of a model of a Russian farmhouse – is the Hunting Tower. The dwelling was built in 1582 for Bess of Hardwick by architect Robert Smythson, and renovated and decorated by Debo. The Hunting Tower contains four-poster beds and, says Bitton, “you can stay for as long as you can afford”.

Sadly, no staff are at your beck and call, and no afternoon tea is served with scones, livery and linen and all. It’s self-catering only but you can always stock up at the farm shop.

The success of Chatsworth today is both a blessing and a curse.

“We are a victim of our own success,” says Bitton. “The local people are so proud of it, a national treasure, and it’s still a private property, going from strength to strength. Every bit of admission money goes back into the house. The more popular we are, the more we can keep it going,” she says.

“I remember Madonna because she came incognito to visit the duchess. She was writing a play or a film she was directing about Wallis Simpson. At the time, the Duchess was one of the only people still alive who moved in those circles, so she came to talk with her and share her experiences.

“I was a guide at the time. I remember her walking around the house with a baseball cap and nobody recognised her. But I did. I thought I was seeing things. She was very humble. She stayed for a couple of days, at least.”

On a more mundane level, work remains to be done on the house, in particular the restoration of the north wing.

“We have scaffolding going up as we speak,” Bitton says. “It’s the 1830s part, the modern extension, and the scaffolding will be up all year. It hasn’t been rewired since the 1950s. We do get leaks with heavy rain, and much money will be spent on the roof.”

She returns to the subject of the exhibition of Beaton’s photographs. “Oh, I’ve had a peek at the photos. That will be my next favourite thing. Stunning images and more modern than anything you’d see in Downton Abbey. The Duchess’ life will amaze a lot of people,” she says.

But Debo was following in the footsteps of generations of noblewomen that led amazing lives.