With the 50th anniversary of the historic Moon Landing on the 20th of July 2019, National Geographic collaborated with acclaimed documentary filmmaker Tom Jennings (Challenger Disaster: Lost Tapes and Diana: In Her Own Words) to re-tell the story of the Space Program of the United States. The documentary Apollo: Missions to the Moon was released in Hong Kong and South East Asia on the 13th of July and officially kicked off National Geographic’s Mission to the Moon Programming Event- which features a whole array of documentaries being shown till the 3rd of August.

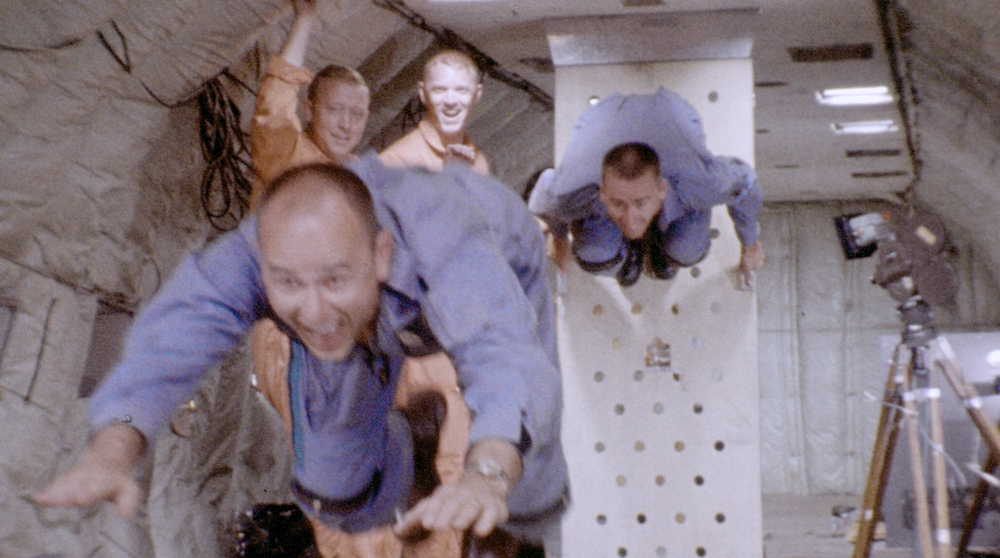

The film itself features archival footage, photographs and audio from all twelve manned missions including recordings that have not been heard before. Drawing on Jennings’ signature style, the film does not rely on modern day narration or exposition but rather counts on visual elements and audio clips from during the time of the missions.

This deliberate movement away from what National Geographic calls “modern-day talking heads”, has also been seen in other documentaries in recent years like Honeyland by Ljubo Stefanov and Tamara Kotevska and Surire by Bettina Perut and Iván Osnovikoff. We were able to sit down with Jennings to talk about how the film was put together and the difficulties of the unique format.

Could you just tell us a little bit about the documentary, in your own words?

Yes, it’s a two hour documentary on National Geographic Channel. It’s about all the Apollo Missions to the moon. Not just Apollo 11. This summer is the 50th anniversary of the moon landing of Apollo 11 but our film is from basically Sputnik, the Russian satellite launch in the late 1950s all the way through to the Space Shuttle. So, we cover the United States in its effort to reach the moon. And we do that in film with no narration, and there are no modern day interviews from today, only interviews done at the time. So then the film feels like a time machine. You go back in time with all of this archival imagery that’s put together from news and radio and other sources and behind the scenes at NASA and you feel almost as if you’re living through the events that led up to the moon landing and then for the other Apollo missions into the early 1970s.

What drew you to this topic in particular? Why the moon landing? Or, why the Apollo Missions?

The network asked me to do it. I did a film a few years ago in a similar style: no narration, no interviews, about the Challenger Space Shuttle Disaster in 1986. And we did that for the 30th anniversary of the Challenger and then we did another one about Princess Diana. Nothing to do with space travel but it was for the 20th anniversary of her death. So, that was in August 2017 and that also worked very well for National Geographic. So, they like this style very much and they very much like anniversaries so they asked me to look forward in the calendar and see what big anniversaries were coming up. And, one of the ones that I noticed was the moon landing.

But in talking to them about it, we knew that there would be a lot of moon landing anniversary documentaries because that’s what happens in major anniversary years. So, we decided not to focus on the moon landing, Apollo 11, but to do the entire Apollo Program. That way we were doing something different. So, the idea came out of a discussion with National Geographic about what events would fit this format that we have developed and we both decided that doing something for the 50th anniversary of the moon landing would be a good way to go.

So, when you approach making documentaries the way that you do in this particular style, you have to interact a lot with videos and primary sources. Do you find that you end up learning new things about the projects that you’re working on?

Oh, all the time. I think I love doing this format because you learn new things through experiencing what was going on back then. In more traditional formats, you can interview people and they can tell you stories or they can tell you what it was like, but, by going through the footage from the time period that journalists and other people were reporting when these events took place, it’s much more experiential. You’re experiencing it as it happens because that’s where the footage and source material comes from, you know, as it happens. This source material has been locked in vaults for years. we used a lot of local news footage. We don’t always use national stuff like Walter Cronkite- we try to avoid Walter Cronkite when we can because he’s so familiar and we want to make everything feel new.

So, I can probably think of several things that I’d never heard of before, but just going through the footage I would learn all kinds of wonderful new things that I wouldn’t have probably learnt about otherwise. Things like, just the personalities of the astronauts. I was very very young, I was old enough to have been alive when the moon landing happened but I remember the astronauts being almost god like back in those days and for good reason, but, in watching the footage, you realise, they gave a lot of interviews, and for people who were adults at the time, you know they may have been heroes but they weren’t gods- they were people on a mission and they were going to get there. And they had very interesting personalities that I was not aware of before I started watching hours and hours of footage. So that’s an example of something that you wouldn’t get necessarily from reading a book.

And when you were going through all of this footage, would you say that the quality of the recording evolved over time? I would imaging that from Apollo 1 all the way to the Space Shuttle, the way that things are recorded changed. What were some of the changes that you noticed when you were going through the footage?

The first live broadcast from space was Apollo 7 where the astronauts were just going around the Earth and were broadcasting back from space, It was the next Apollo after the Apollo 1 fire. And, that broadcast from space, you could make it out but it’s very grainy black and white, you know, it’s miraculous that they were able to do it in the first place. And by Apollo 11, it was getting a little better. Plus They were taking still photographs and when that films came back it was as good as any film from the time period but the time they got to Apollo 15, 16 and 17, which were the last missions obviously, the footage they were able to send back to earth, was just stunning and it’s kind of strange in a way that in telling these stories, the most dramatic stories came early on. You know, there was the tragedy with Apollo 1, there was the first television broadcast of Apollo 7, there was Apollo 8 where it was the first manned spacecraft to get beyond the gravitational pull of the Earth and actually go around the moon, and they took the famous Earth-rise photograph. And then of course, Apollo 11, very dramatic and Apollo 13 where they almost died in space because of the explosion.

The footage gets better as you say, but by the time they got to the last few missions where they were doing really high end science for the time, exploring the moon, the images are by far, the best images but unless you’re really into whether or not there was water on the surface of the moon at some point through oxidation, it’s not very dramatic. The stories are just not as dramatic as the ones that came earlier. So, the real drama came really early on when the images aren’t quite as good, whereas the most pristine images come from the last few missions, where there wasn’t nearly as much drama because they had refined how to get to the moon, but still they made great discoveries.

So, you mentioned that you don’t really use narration or modern day “floating heads” so could you explain a little bit about what the audience can expect when they go to see the film? So would it just be a series of old films that you can see in a timeline? What transitional devices would you use if you don’t use narration?

Well, it plays like a movie. It plays as if we went out and shot these scenes as they play in our film as a scene in a motion picture. We use multiple sources like radio, television, maps, advertisements, anything we can get our hands on. Mission control audio and video, images from inside the space capsule, obviously from the moonwalk, we put it together in a way so that the story is seamless. Occasionally, we’ll put up a time and a date or which mission we’re at. It’s kind of a book end to the next section of the film, but we’re able to take the media at the time and put it together in a way that makes sense, that they may become our narrator, they being broadcasters, the astronauts, the people inside mission control. We take all of these people that are telling their story at that time and we figure out a way to put it together that it makes sense today and then we add images that complement what they’re saying so that the viewer, let’s say they were sitting in their living room and flipping through channels, it would feel like they’re flipping through the channels in 1969 during the Apollo Mission but as they’re flipping channels, the story is seamless, there is no cutting. It just flows together from sequence to sequence to sequence, the whole idea is to make you feel like you’re sitting there watching it as it’s happening. But, you’re not just watching non stop news like CNN just playing for 24 straight hours. We’ve taken all those images and curated them into two hours that feels like you’re watching a movie.

And how long did this curation take? How many hours of footage did you have to sit through?

Many hundreds of hours (laughs). It’s hard to say exactly how many, because we got hundreds of hours from NASA alone but then we would full hours, maybe a dozen, from a particular television station in Houston, maybe a few television stations we found in South Florida near Cape Kennedy where the rockets were launched, you know, any kind of news source, National Geographic Magazine itself which a lot of documentarians don’t think to go to when they’re looking for news orientated stills, photographs. They have an amazing collection of Apollo images because they were following it the same way that CBS was following it so we were accessing a library that no one had looked at in a long, long, long time.

The big find that they like talking about is, when you watch documentaries about the Apollo missions in the past you would one person standing in the middle of mission control talking to the astronauts. And that person is called CAPCOM (Spacecraft Communicator). That’s their nickname. CAPCOM talks to the astronauts, the astronauts talk to CAPCOM. And what’s been digitised up to this point, is only the audio from CAPCOM, the mission control director talking to the astronauts. But if you look around the room, there’s hundreds of other people sitting at computer consoles. And, amongst those other people, NASA recorded thirty of them, audio recordings, talking to each other, talking to CAPCOM. CAPCOM was the only one allowed to speak directly to the astronauts, that’s why he’s the only one we hear, so you can imagine, thirty people talking during an entire Apollo mission that would be a couple of hundred hours long and multiply that by, what, eleven manned missions of Apollo. There is something like 10,000 hours of audio on this thirty track, of all these people talking to each other.

And if you watch the film, we’re able to access a lot of this mission control thirty track so that you’re hearing what’s going on in the background for the first time. It’s almost like music to me. You’re hearing all of these voices talking and we bring one up that’s monitoring the heart rate and the oxygen levels of the astronauts, and we bring one down, then someone’s looking at the guidance control system, you know, so we got to play with all of this audio and by no means did we look at 10,000 hours. We just went in and looked at the highlights that were being digitised and to have that, when you put it against the footage where you can marry it together, everything comes to life in a way that you haven’t experienced it before. It’s like magic.

I know that NASA would probably keep very extensive records of what happened during all these launches and missions, how easy was it to obtain footage from, say, local newspapers, or advertisers or television stations?

Well, if they kept it, they would share it. Doing many films in this format, I’m amazed that even for major events, that have occurred since the beginning of recorded film and video, tv news stations, the local ones, don’t often keep their archives. Or if they do, they just keep what was cut and put on the air. One thing that we always ask for is that we want the raw footage, because if you think about how TV news works, there’s a camera operator out and they’re shooting and shooting and shooting some event going on, you know, coverage of one of the rockets going up during the Apollo Missions and then they rush that footage back to the news rooms and to an editor. Say the reel or the tape is 30 minutes long, well, that editor will go through and maybe pick four or five minutes that they like best and make a copy of those four or five minutes and then take that tape out of their editing machine and they’ll put it on a shelf and you’ll have 25 minutes that will never see the light of day ever again.

And oftentimes, especially back in those days, tapes were very expensive when they were changing over to video tape for example. So the stations would often tape over the previous day’s (footage) once they had gotten their cut pieces for broadcast. They would just say, “Well, here’s a bunch of tape from yesterday, take those camera operator and go and shoot over on top of what we shot yesterday”. So a lot of stations don’t have their stuff anymore. Thankfully, some do (laughs). And there are a lot of television stations in the United States, local news stations, and then there are, like in my home state of Ohio, there’s an Ohio News Archive where all the news stations, kind of, send their material to one central place and they curate it for history and we can go to them and they can go and look in their archive and see what they have.

So, there’s a lot of material out there but I kind of cringe when I think at the same time how much material was lost. Either thrown away or taped over or actually sitting somewhere but no one really knows whats on it. So it’s risky when you begin because you never know what you’re going to find but we always find a lot more than we think we will.

And speaking about beginning, usually when you’re thinking about documentaries, I find that some filmmakers realise in the process that they have to change gears, approach it from a different angle. Do you experience the same things when you’re going through archival footage as well?

I don’t know if we change the angle as much for these anyway because we kind of know going in, after having talked to National Geographic for example, we know they want something for the anniversary of the moon landing, we know they want it to be different than anything everyone else is going to be doing which mostly is going to focus on Apollo 11. So, we know we’re going to do all of the Apollo Missions. We kind of know that going in. And then we kind of ballpark the major points along the way that have to be told because they are such seminal moments. And, what happens to change that is that we don’t necessarily change the big story arch, but we will alter the stories within that arch based on how good the archive is. For example, we weren’t really going to focus that much on Apollo 7 other than that it was a success because it was the first manned mission after the fire on Apollo 1 and in looking at the Apollo 7 stuff, we realised, the mission control footage from when they did their first broadcast from space was pretty good. The broadcast itself wasn’t very good but the people in mission control and their reaction to being able to have astronauts do a live broadcast from space was great.

Then we found that the astronauts went on a talk show for a comedian at the time named Bob Hope, he had a variety show- he was a very famous comedian- the Bob Hope show. And he had the three of them on there and he was talking about how their ratings from space weren’t very good and that he was the expert on how to get great ratings and it was a very funny moment and this is an example of what you’re talking about, where we were barely going to acknowledge Apollo 7 because we wanted to get to Apollo 8 which was when they went to the moon for the first time and went around it. But the more we saw of Apollo 7, the more we thought well we have to make this more of a story, this is hysterical. They wind up on Bob Hope and everybody’s laughing and it’s such a great moment.

It’s such a perfect moment because Bob Hope says, “ How do you think I know how to get all these great ratings and I’ve been on the top of this game for 25 years”, and one of the astronauts looks at him and says, “Luck”. And everyone laughs and and then he (Hope) says, “Watch it, nobody likes a smart ass-tronaut”, you know, which was like off-colour humour at the time. It was a little nuanced moment because the whole audience laughed like, “Oh my God, he was saying ‘smart ass’ instead of ‘smart astronaut’”, and that was considered very racy, for us today that’s nothing. But for them that was very daring television. And so when we saw that, we were like, “It’s gotta go in”, because it takes you back to that time better than anyone could explain it because you get to see it. And there’s probably a dozen instances like that where we find something and say, “That’s gotta go in” and change the story a little bit.

So, you had mentioned Sputnik in the beginning and now we know that the moon landing and all the space related explorations were part of the Space Race and how that factored into the Cold War, does the documentary touch on that or is that something that you don’t really see in the tapes?

No, it’s there. When the Russian Space Program launched Sputnik, the Americans weren’t very happy so it lit the fire under the United States government that, you know, “We better do something about this”, and then led to President Kennedy eventually saying that we’re going to go to the moon. And that was the big race. So, it’s there at the beginning as kind of like the catalyst for everything to follow. And, it’s mentioned a few times throughout but once we get into the full Apollo Program, especially after the Apollo 1 fire and then Apollo 6’s problems, it just becomes this journey of exploration- an exploration the likes of which have never been seen. So, we focus much more on that.

The Russians are still in the background and they’re mentioned every now and again as part of a news report of what’s going on with them, and as part of a headline but once we’re about halfway in, you don’t really hear about them again. Just a slight mention near the time of the moon landing but it is at the beginning of the film and it is what gets the entire Space Program in the United States going. The Russians were very very far ahead of us and that comes out in the film- how they’re sending guys into space and we don’t even have a rocket yet. It’s part of it but I wouldn’t say that it’s a big part of it.

So, there is a lack of narration in the film and we have seen that recently there have been a lot of documentaries that only focus on the action that’s going on at that time and they don’t have traditional interviews. In your opinion, do you think this could be a new wave of documentary filmmaking or a new trend that will allow us to explore more about what we can do with visual elements as opposed to just telling people what’s happening?

I mean, it’s a double edged sword, because by only using the media that was available at the time, you don’t get the luxury of retrospection, of looking back, of understanding. That is a drawback of the format. However, I think that the format functions at such a high level in transporting people back in time and creating almost a time machine through film and video and audio that we try to understand well, what were these people like, what were they going through, what was their sense of humour like, what was it like to be alive at that time and experience that and you can listen to a lot of talking heads tell you what it was like but the goal of this format is to create a visual experience, a film experience that allows that, even for a brief moment- my goal is that, even for the briefest of moments that an audience member is watching this, it feels like they’re taken back to the 1960s because it’s so real to them, then we’ve done our job.

I think there are all kinds of ways to tell a documentary story and this is one of them and I think it’s very powerful and I also think that it’s very pure because we try very hard not to editorialise in any particular way, we just present the story as best we can with the media that’s available. Sometimes, that gets in our way because we wish we had more media available to us for certain parts of the story- but in general, what we’re trying to do is create an experience that gets you as close as possible to the actual event.

The schedule for the rest of the “Mission to the Moon” Event is as follows:

- “The Armstrong Tapes” (Premiers on July 20, 2019, 9.00 PM HKT)

- “Rookie Moonshot: Budget Mission to the Moon” (Premieres on July 20, 2019, 10.00 PM HKT)

- “Apollo: Back to the Moon” (Premieres on July 27, 2019, 9.00 PM HKT)

- “Apollo 8: The Mission That Changed The World” (Premieres on August 3, 2019, 9.00 PM HKT)

- “Challenger Disaster: The Final Mission” (Premieres on August 3, 2019 10.00 PM HKT)