An artist who seems to bring an entirely new meaning to the term detail-oriented, Tom Friedman crafts intricate works that bring an air of illusion to any room they occupy. As Yana Fung discovers, you’ll need more than just a cursory glance to understand what’s really going on

When it comes to looking at art, most would agree that at least a few seconds – if not minutes – are required to adequately appreciate a piece. General consensus seems to be that a speed walk through an art gallery is a faux-pas. Even so, it can be said that Tom Friedman’s work demands a bit more time than usual.

Born in the midwestern US city of St. Louis, Missouri, and now based in Leverett, Massachusetts, the conceptual artist explores ideas of perception, logic and plausibility in genres spanning sculpture, painting, drawing, video and installation. His art is created with such attention to detail that it would seem to have been produced in a factory by machines. New York’s Guggenheim and MoM A are among the many museums that have recognised Friedman’s talent with solo exhibitions. Now, it’s Asia’s turn with the announcement that esteemed gallery Lehmann Maupin is representing the artist in the region.

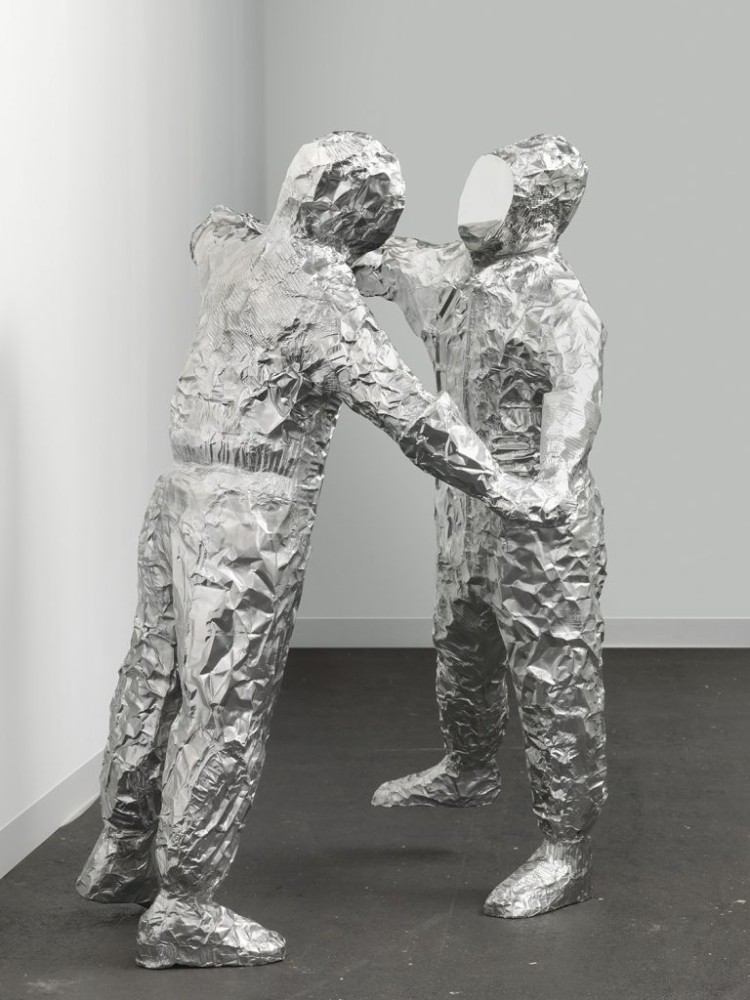

While the materials Friedman uses – Styrofoam, foil and hair, to name a few – might seem unconventional in the art world, they are an all too familiar sight in our daily lives. Used almost sarcastically, they give Friedman’s work something akin to the edginess of dark humour. They also bring a sense of relatability and tangibility to the viewer, amid the largely intangible concepts the artist tackles.

“Empathy can be a practice where you consciously think about someone else’s beingness. Mathematically, this is looking for the common denominator,” he explains. “Everyone creates their world. My life is about my world with an interest in its intersection with my theory of other people’s worlds.”While Friedman’s inspiration might come from his own life, it’s clear that this isn’t intended to shut anyone out. From subject matter to material, the artist’s intent is to draw people in. “The materials I choose can best, in my mind, convey my idea and draw the viewer into the experience,” he says.

With pieces like Friedman’s, one would expect that each is the result of countless sleepless nights and intense staring until eyes start to water. In actual fact, he says, “Some pieces take a moment, and others can take a year.”Whether art is created in a flash or slowly takes its form over the course of 12 months, it all must start somewhere. For Friedman, that somewhere is a kind of final destination. “I think about the body of work I am, or going to start, working on. I begin from the place where this body of work is going,” he says. Before he moves forward, he has to look back: “I then look to my past works as a progression and then invent from there.” If he looked back now, Friedman might find some ominous foreshadowing about the pandemic in Hazmat Love from 2017. Although at the time, the recent Ebola epidemic may have been a more relevant and timely issue.

Also see: Take a virtual tour around these 5 world-class museums

For Friedman, looking back includes looking at the bigger picture of his oeuvre. “I think about each piece in a body of work and how they relate to each other,” he says. “I try to make very disparate works so one looks for relationships between the pieces. ”What actually happens when a new piece is starting to be created is best described by the artist himself, “I say I build my work from the atom up.” It’s a deceivingly uncomplicated reason for why much of his art is so detailed and realistic. One look at his pieces will reveal that they are anything but uncomplicated.

While it’s clear what is art and what is real, a giant life-like pizza hanging on the wall might just be enough for the suspension of belief. Created in 2013, Untitled (Pizza) is made of mundane yet more toxic ingredients than actual pizza: styrofoam and paint. Of course, to most, crafting such painstaking details seems like an insurmountable and futile task to undertake. To Friedman, precision seems to be a more relative idea. “Detail or precise is something that is based on how close you are to the piece,” he says. The way he sees it, the level of detail he produces isn’t even meant for getting extremely close to an art piece. “I work for a precision that is average eye-focus distance.”

Another testament to Friedman’s painstaking commitment to detail is his starburst construction made out of 30,000 toothpicks. From a distance, it appears to be an impossible disruption of the laws of nature and gravity. What looks like a gravity-defying explosion of sand in the shape of a supernova is really a careful construction of more toothpicks than anyone will ever use in their lifetime.

We’re left to ponder the connection between the subject matter and the material, which Friedman assures us does exist. In fact, Friedman sees art as an environment for people to pump the brakes on their hyperspeed lifestyles. “I just want them to slow themselves down and experience something,” he says. It’s about giving the viewer a space to contemplate something new that had never crossed their mind before or approach something they already knew from a new angle.

Other pieces, like Being or Up in the Air, give viewers an abundance of things to see, almost leaving an Easter egg hunt of clues and items for viewers to recognise. Being, a humanoid sculpture stuffed to the brim with everyday items, blurs the line between reality and fantasy.

According to Friedman, “Everyone’s reality is also fantasy.” Where does that leave a fantastical human-like figure full of real man-made items? Maybe we find ourselves in a kind of hyper-reality where rationality and imagination collide, as our sense of perception goes haywire. This is unsurprising, given Friedman’s evolution. Since his university days in St. Louis and Chicago, his art has taken what seems to be a complete turn away from the rational.

“In university, I was looking for logic. Since then I am looking for things I don’t understand,” he says. Perhaps the infallible logic of art is that purely logical thinking has no place in it. The constant battle between the logical and illogical might just be where conceptual art is born. After all, how else would we explain the detritus of everyday life taking on a supernatural quality when seen through an artist’s eyes?

Also see: The brave new world of NFT