Diamonds have, throughout history, been as much revered as they have been reviled. Throw lab-grown in the mix and there are more debates than ever. Sandrine Conseiller, CEO of De Beers Brands, and Wes Tucker, CEO of Tracr, help Zaneta Cheng make sure no stones are left unturned

Are natural diamonds really going to last forever? In an age when provenance and transparency are king, and ever younger consumers are increasingly determined to shop mindfully and ethically, the debate over natural-mined diamonds and lab-grown varieties has become more prominent than ever. Arguments usually centre on ethical and sustainability concerns as well as the structural composition of the two. And while we’ve heard a whole lot about the adverse side of mining, there are perhaps nuances to the cut-and-dry for and against arguments that have been missed amidst the soapboxing.

For this purpose, Sandrine Conseiller, CEO of De Beers Brands, and Wes Tucker, CEO of Tracr, a digital provenance platform that works to trace the journey of a diamond from mine to retailer, offer their expertise around common concerns and misconceptions when it comes to natural diamonds and natural diamond mining.

On whether a lab-grown diamond is really structurally the same as a natural diamond:

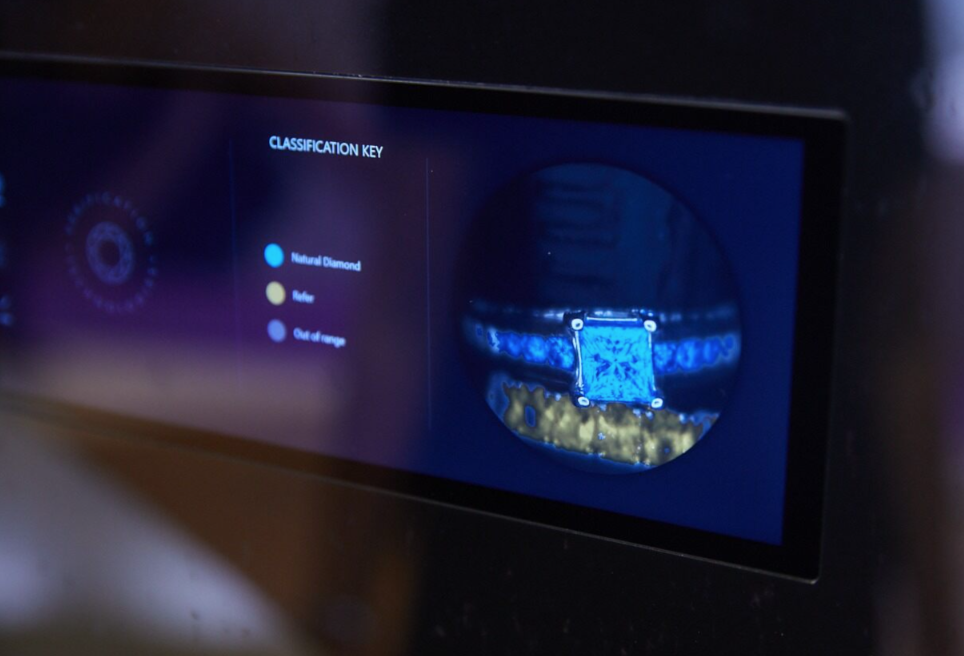

“No, it’s not and that’s why we see the difference. When it’s rough, you can see the difference very easily. When it’s polished, you just need a machine like the De Beers Diamond Proof. We’ve been putting those machines out in the market since 2000 and with one of them you’ll be able to see the difference instantly, just through the colour. And when you look with a very big machine, like a microscope, inside a lab-grown diamond, it’s very man-made. All you can see are squares because it’s been pressure grown in an artificial way whereas a natural diamond structure is a bit like a tree. It’s all organic, so it’s irregular when you look into it.” – Sandrine Conseiller

On the community impact of lab-grown diamonds versus natural diamonds:

“You could have a lab-grown diamond made in a factory as opposed to a natural diamond, but it doesn’t help the communities. It doesn’t help the community in Sierra Leone if people are buying diamonds that are manufactured in a factory and cut and polished there. As you can see, having come from those areas myself and working in those countries, this is a personal passion of mine. I go to a lot of conferences where we have many of these types of conversations and I say, ‘Look, guys, the answer is not to stop mining because if you don’t mine, then what happens to these communities?’ How do we help them raise the bar and get the infrastructure in place? The answer is doing it well in partnering and collectivising.

I think in all industries in the world, there are many bad examples. That could be textiles. You know, Southeast Asia, there have been challenges in the market with luxury brands. So we’ve got to look at the places where we have good examples of how this is working and improve on that. The diamond industry has a lot of good. They’ve got their challenges but they definitely have a lot of good examples.” – Wes Tucker

On mining as an exploitation of developing markets:

“I come from South Africa. I was born there and I grew up there, and obviously we’re an emerging market and emerging economy. I worked a lot in Africa, which is

a collection of a lot of other emerging economies, and mining is a big part of that. So there are a couple of things that I like to explain to people – my opinion, when it comes to mining in general, but I’ll speak specifically about diamond mining here.

If you think about the rest of the world, the First World, they all went through this kind of industrial revolution and industrialisation and in that period of time they mined, manufactured and built infrastructure, and most of it was within their country. They either got resources from their colonies or they mined them within their own country, so they had a perfect uninterrupted ecosystem where they were able to self-develop using a huge amount of coal power.

You go to the UK today and they have amazing infrastructure because they were able to build it on the back of mining a hundred years ago. Whereas today you’ve got these emerging economies that are trying to build that same infrastructure for themselves, but they don’t have the money that other countries had before and the world has obviously moved on quite a bit. What these countries do have, however, are their natural resources – whether that’s lithium and cobalt that goes into your phones, or it’s gold or platinum or iron ore or diamonds.

The first thing to know is that a lot of that value goes back to the host communities, but it depends on getting the model right. When we speak about diamonds, they’re a great example of transferring wealth from the First World into the Third World through mining. If you look at Botswana and look at the number of roads, hospitals and schools in the 1960s or ’70s, and today where there’s free healthcare, free education and 6,000 to 10,000 kilometres of roads that have been tarred, a lot of that has been a result of the diamond economy.” – Wes Tucker

On the impact of mining on nature:

“The sustainability programmes at De Beers are very strong. That’s one of the reasons why I joined the company, because it matters to me. We have three types of sustainability goals. One based on livelihood, or how we can positively impact the lives of the people and the communities in areas where we have mines, one based on nature and one based on climate.

Regarding nature, we have a net positive commitment, which means that if we disturb nature we will restore it. That’s why we have reserves around our mines. We have 200,000 acres of reserves, so when you work at a De Beers mine, you will see animals because they have been actively preserved for 50 years.

We also have a partnership in West Africa with national parks like Zinave National Park in Mozambique, where we have over 1 million acres that we contribute to the preservation of. This reserve was actually dying and not very well maintained at first. There was an issue with a lack of animals and we realised that in Botswana there was an area that had too many, so we moved more than 100 elephants to Mozambique and now the park has been completely revived such that not only are the elephants thriving but other species have been able to come in.

It’s opposite to the beliefs that most people have around diamonds. I think we’ve been a very secretive industry for a long time and we don’t tend to speak up about what we do. For example, most people find it surprising when they visit the mines that no chemicals are used so you basically dig soil and filter it for the diamonds. Many other metals, including gold, involve a lot of chemicals in the process. We also have partnerships with, for example, National Geographic in the Okavango Delta, so when you buy a diamond, you do good.” – Sandrine Conseiller

Also see: Gift Guide Christmas 2024: Top jewellery pieces to glam up your holiday