Dior Spring–Summer 2026 by Jonathan Anderson

Paris, on an unseasonably cool afternoon of fashion week. The footsteps of hundreds of guests echoed against the marble of the Tuileries Gardens, then faded as the lights inside a vast tent suddenly went dark, leaving only the flicker of a massive screen above a gray marble runway.

White letters appeared, bold and defiant:

“DO YOU DARE TO ENTER THE HOUSE OF DIOR?”

A single sentence, equal parts invitation and warning, opened Jonathan Anderson’s debut womenswear show as the new creative director of Dior.

What followed was not merely a fashion film, but a psychological assault on the expectations of every person who entered that “house.” Anderson had enlisted British documentarian Adam Curtis, master of archival collage and social unease, to create a short film that spliced vintage Dior runway clips with black-and-white horror imagery from the 1960s and fragments of Hitchcock’s Psycho. The result was a hypnotic hallucination, beauty and terror entwined, that held the audience in tense silence.

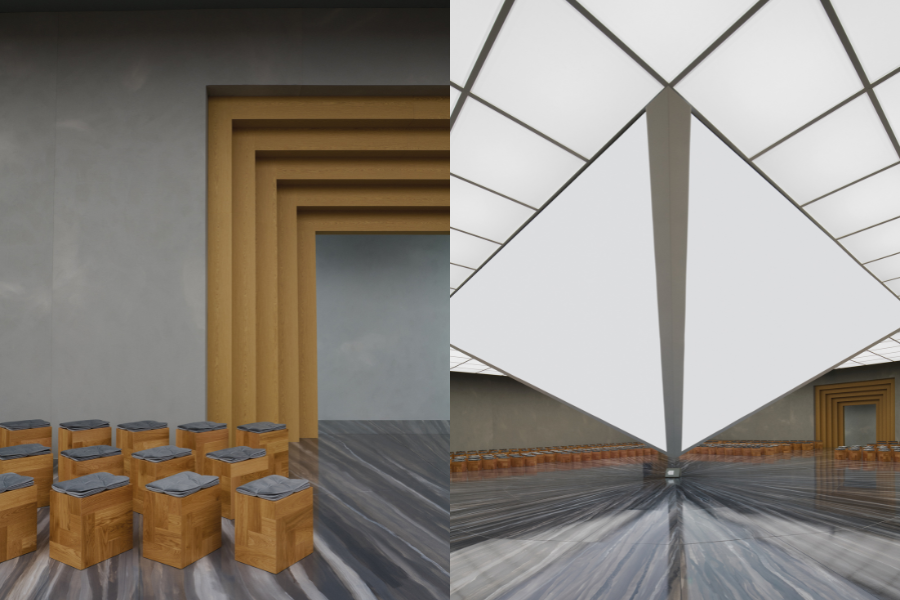

The film was projected onto an inverted pyramid, a bouleversé version of the Louvre’s glass landmark, symbolizing a reversal of history itself. The footage spun backward in chaos before being sucked into a Dior shoebox at the pyramid’s tip, a modern Pandora’s Box that refused to close.

“I love the idea of a box that never shuts,” Anderson said backstage. “Fashion is like that, it never sits still long enough to close the lid.”

And when the lights returned to the runway, it was as if that box had indeed been flung open.

That night, Dior didn’t just invite an audience, it summoned an entire universe of expectations. The front row was a constellation of power and beauty: Anya Taylor-Joy, Charlize Theron, Jennifer Lawrence, Jisoo, Jimin, Greta Lee, Rosalía, Willow Smith.

At the center, Delphine Arnault sat between Brigitte Macron, France’s First Lady, and Johnny Depp, the face of Dior Sauvage. It was a living power map of the new Dior era, at the very moment the world waited to see what “the next chapter of luxury” would sound like under JWA.

Anderson took the runway as the first designer in Dior’s history to oversee both menswear and womenswear, a double crown heavy with pressure.

“I’ve never felt so much pressure in my life,” he admitted. “There was a time when liking fashion was cool. Now it seems that destroying fashion is cooler. Everyone has an opinion. Everyone is ready to judge instantly. So I wanted to begin by asking, Do you dare to come into this house?”

Thus, Dior SS26 was not a celebration, it was a provocation.

Anderson described his approach as “Rewiring the Everyday.” He borrowed the visual grammar that made him famous at Loewe: taking something familiar, then twisting it into the uncanny. Think: silk jersey tops with tuxedo bib leggings, mini crocodile purses, or the legendary Bar jacket, shrunken to doll-like proportions and paired with flaring pleated skirts that fluttered like school-gym uniforms.

“I don’t want an army of people who look the same,” he insisted. “I want different women, because if everyone starts to look alike, it mirrors what’s happening in the world right now.”

The 74 looks on the runway were deliberately unruly, chaotic with precision. Denim appeared in unprecedented abundance for Dior: faded, frayed, tailored into capes and military jackets. Topping them were tricorne hats by Stephen Jones, whose brief was, Anderson said, “to look like stealth bombers, flat, sleek, a little menacing.”

Some critics saw this as a youthification of Dior; in truth, it was a resuscitation.

“I grew up watching John Galliano’s Dior,” Anderson said. “He’s the reason I fell in love with the house. I want to honor that madness, but I also want to create my own.”

Up close, Anderson hadn’t abandoned Dior’s heritage so much as tilted it on its axis.

The Bar jacket re-emerged as a cropped shell; bubble dresses bloomed in smoke-light lace; plissé satin blouses carried rigid lace collars arching like rooftops above liquid skirts.

All of it played on what Anderson called the tension between “harmony and strain.”

Standout moments included Julia Nobis in an ivory hydrangea-silk tiered dress—a nod to Monsieur Dior’s favorite flower, its translucent layers built like petals about to fall.

“I’m obsessed with hydrangeas,” Anderson said. “They’re beautiful because they die quickly. Some kinds of beauty you have to let fade, to remember them better.”

Another unforgettable look: massive culottes, a smocked blouse, a trailing black lace veil, and a crushed tricorne hat, Anderson’s tribute to Yves Saint Laurent’s brief yet brilliant Dior years.

“I love that period,” he said. “It was so unstable, yet filled with unfinished beauty. I wanted to hold onto that feeling.”

Uncertainty became the hidden theme of the show, both in fashion and the world beyond.

Anderson’s answer to the noise was quiet.

“Everyone’s shouting to be heard,” he mused. “But sometimes the most powerful thing you can do is whisper, and let the clothes speak.”

The result was not the sugar-coated fantasy some might have expected. It was something stranger, a house haunted by beauty. The clothes weren’t sweet, but emotionally sensual: some trembling with Galliano’s theatricality, others serene in Anderson’s restraint.

“I don’t want Dior to become Loewe,” he emphasized. “I want Dior to be Dior, but a Dior with a pulse.”

On the business front, Delphine Arnault knew the risk came with a price. Dior remains the crown jewel of LVMH, yet the global luxury market has begun to cool in 2025. Placing Anderson at the helm wasn’t just an artistic gamble, it was a cultural rescue mission.

And it worked. Adam Curtis’s film went viral overnight; the “Dior box that wouldn’t close” became a meme; the star-studded front row flooded social media; and earned media value skyrocketed within 48 hours.

Meanwhile, the merchandise was primed: the new Cigale bag, inspired by an archival gown of the same name, was already tipped to become the next “It Bag” of 2026, assuming the price lands right. Footwear designer Nina Christen delivered everything from chic loafers to giant-flower mules in slightly grotesque chic tones, covering all tiers of luxury appetite.

When asked about the crushing pressure of leading both Dior’s men’s and women’s lines, Anderson paused before answering softly:

“It’s not about being right or wrong. It’s about working with ideas, and that’s where good fashion begins.”

Perhaps that’s why Dior SS26 feels like Pandora’s Box left ajar, buzzing with criticism, fear, hope, uncertainty, and imperfect beauty that somehow breathes.

In a world where every brand screams to be heard, Jonathan Anderson’s Dior chose to whisper, and the entire room fell silent to listen, waiting for what comes next.

Because sometimes, the bravest thing in fashion is simply to open the box again, knowing it could all go wrong,

and doing it anyway.