C³: Chanel, Cinderella, Couture

Chanel Haute Couture Spring/Spring 2026: When Chanel Learned How to Breathe Again

Reported by Manit Maneepantakul

Matthieu Blazy did not enter the world of Chanel Haute Couture as a “heir to the throne,” nor as a “liberator of the brand from its past.” Instead, he chose a far more subtle and complex role: that of someone who lightens the weight of expectation carried by a fashion house burdened for over a century with symbols, history, and immense cultural authority. And this “lightening” does not mean making Chanel weightless or fragile; it means allowing a house long expected to be “great at all times” to breathe naturally again. Blazy did not choose power, spectacle, shock value, or an aggressive rewriting of the archive. He chose instead the lightest materials available to fashion as a system: dreams, silence, transparency, weightlessness, and emotions that do not require explanation.

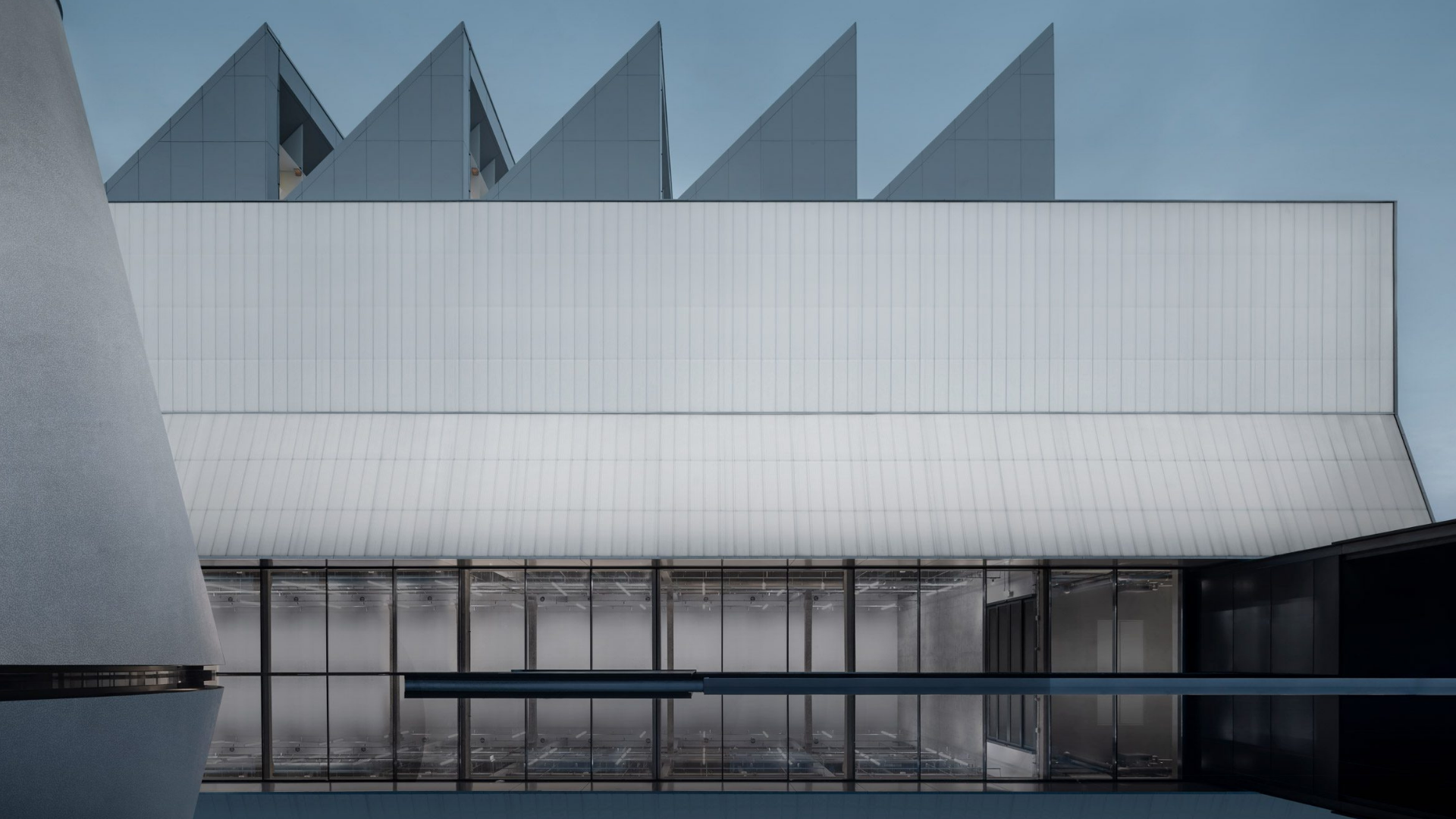

The pale pink set at the Grand Palais, filled with giant toadstools and pastel weeping willows, was therefore not designed for grandeur, but to create the emotional climate of the collection, a world that feels light, soft, gentle, and safe enough for meaning to slowly reveal itself. This psychedelic Wonderland of mycelial rings and mushroom forms was not merely a backdrop, but a declaration that Chanel in Blazy’s hands is shifting its center of gravity: from performance to dreaming, from image to poetry, from monumentality to breathing. This sensibility was foreshadowed by the opening animation of woodland animals working in the Chanel atelier, Cinderella-style. It was not a whimsical visual trick, but a clear articulation of Blazy’s philosophy: Haute Couture is a world of craftsmanship (petites mains), time, patience, and love for process, not a factory of image production. “I wanted something light, poetic and easily understood. Making something light also allows me to dial down the drama.” This is not a tagline, but a manifesto for a new Chanel era. Lightness here does not mean superficiality; it means reducing noise, pressure, and the accumulated weight of decades of expectation.

What gives this lightness real gravity is its origin. The collection does not begin in the Chanel archive, in classic silhouettes, or in fashion history, but in a three-line haiku that Blazy describes as having struck him “to the core”:

Bird on a mushroom / I saw the beauty at once / Then gone, flown away.

He speaks of it like a small discovery that changes perception. In a world saturated by daily crises, he imagined couture as a parenthesis in life, a pause, a dream, a poetic interruption. Even a 20-minute escape from reality, simply “throwing poetry on the table” for the world to see again. A bird on a mushroom, simple, almost nothing, yet enough to make Chanel feel alive again.

From this haiku, birds, mushrooms, beauty, and transience became the conceptual spine of the collection. Mushrooms appear most visibly in the Grand Palais set and in details like Massaro shoes with fantastical mushroom heels topped by tiny birds, like punctuation marks in a poem. But the true emotional core of the collection is not mushrooms, it is birds. In Blazy’s studio moodboard there are no fashion references, no couture archives, no historical silhouettes, only photographs of birds, as if nature itself had become Chanel’s new teacher. “I was interested in birds, because they are free, because they travel, because they come from every place. I thought it was a beautiful metaphor for women today.” Here, birds are not decorative motifs; they are symbolic architecture. Freedom not as romantic fantasy, but as contemporary reality: mobility, borderlessness, self-definition, the ability to be minimal one moment and extravagant the next.

We see humble pigeon feathers and extravagant bird-of-paradise cocoons, ravens from Van Gogh’s final painting across yellow silk, and birds conjured not through literal feathers but through raw threads, mother-of-pearl, pleating, weaving, and embroidery, fabric itself becoming alive. From pigeon grey to raven black, heron, cockatoo, spoonbill, and peacock illusions, the collection moves like a visual poem from “ordinary birds” to “dream birds,” never losing its Chanel identity.

But for birds to fly, Chanel had to shed weight. And this is where Blazy’s opening look becomes the sharpest statement of the show. He begins with a philosophical question: “If we take out the codes, the tweeds, the trims, the iconography, can it still look like Chanel?” His answer is a Chanel suit that almost has no physical presence: a sheer blush-pink mousseline/organza skirt suit, pink quartz buttons, the classic hem chain updated with natural pearls, two-tone slingbacks he calls “anti-pumps,” and a transparent 2.55 bag cut from the same fabric and suspended on sheer chains like an extension of the body. “Because the slingback and the 2.55 are almost elements you don’t question anymore, like a street, a building, or a pair of scissors. It’s the pedestal of Chanel. You have those, you have the allure.” This sounds playful, but it is profound: Chanel exists in the things we no longer question.

What gives the look its power is not classicism, but transparency, the courage to strip the brand’s structure down to the human body. The lingerie beneath is not erotic; it is structural, emphasizing physicality. Blazy insists that couture is not for images, it is for bodies. “It was about this idea of women in motion? of freedom, and clothes that don’t constrain her.” Couture here is not brand architecture, but human biology: breath, movement, rhythm.

He then layers story onto the body through what he calls a “lexicon of symbols.” Women choose their own initials, hearts, zodiac signs, personal symbols. When he asked Stephanie Cavalli what she wanted, she asked for a heart over her heart and a love letter from her husband inside her bag. The embroidered letter in the transparent 2.55 contains her husband’s real words, private emotion made visible. “Women bring their own stories into this place,” Blazy says. This dismantles the old Chanel idea of the “total look.” Instead of selling a finished identity, he offers a space, a canvas, where the wearer’s story becomes the meaning.

This philosophy extends into casting. “We didn’t cast 18-year-old girls. We looked for women with maturity from all around the world. I’m more interested in the ones we don’t know.” Stephanie Cavalli (40+), Bhavita Mandava as the bride, Alex Consani, these are not archetypes but lived bodies, lived lives. Couture becomes human presence, not ritualized perfection.

Blazy also reconnects couture to Gabrielle Chanel’s original philosophy of wearability. In Chanel’s time, ready-to-wear didn’t exist; couture did not necessarily mean embroidery or decoration. She made simple suits that were still couture. Blazy revives this with black crepe daywear suits (recreated from Chanel’s original fabric), parakeet buttons, and a simple black dress he loves because it “doesn’t scream couture,” yet inside it is, in his words, “a fucking computer” of complexity. This is his ethic: true couture lives in what you don’t see. “One of the most interesting things about couture is the stuff that you don’t see. That’s what makes it good.”

This leads to his stripping back of volume, jewelry, and ornamentation. Silhouettes become long, linear, quiet, until they move. “Everything looks sexy because when it moves, it goes right above the knee. The body is the tool.” This philosophy culminates in the tank top and trompe-l’œil “jeans,” a Blazy signature from Margiela and Bottega Veneta, here offered as couture as a blank canvas, a space for women to inscribe their own meaning.

The finale soundtrack becomes the emotional thesis of the show. The mash-up of “Bittersweet Symphony” and “Wonderwall” places Chanel at the intersection of reality and dream. “Bittersweet Symphony” is the world: systems, pressure, structure, the bitterness of contemporary life. “Wonderwall” is what humans still dare to believe in: hope, romance, faith in meaning without proof. Blazy’s Chanel stands between them, a symphony of bitterness and sweetness, an acceptance that the world is heavy, but dreams still deserve space. The front row, Dua Lipa, A$AP Rocky, Margaret Qualley, becomes a shared emotional moment, not a controlled PR tableau.

Where his ready-to-wear show closed with triumphant energy and “Rhythm is a Dancer,” this couture ends differently, with Joan Baez’s “Diamonds and Rust.” Sweetness and corrosion in one voice, beauty and decay in the same breath, perfectly echoing the haiku at the root of the collection: beauty appears, and disappears.

“I’m like a cook,” Blazy says. “I prepare all the ingredients, put everything on the plate, and then you hope the magic happens. Some things you can control, some you can’t. A model looks someone in the eye, and suddenly the whole show twists. That’s why a show is a moment, it has to be lived. It can fail too.” But not today.

Chanel Haute Couture Spring/Summer 2026 does not try to be iconic. It does not try to be viral. It does not try to be monumental. It is a beautiful moment, like a haiku that appears, and disappears, leaving behind a quiet clarity: perhaps couture no longer needs to be a monument. Perhaps it can be a pause. A breath. A dream.

Strategically, this is a profound repositioning of Chanel: not competing in spectacle, shock, or noise economy, but redefining luxury as emotional luxury, luxury of meaning, feeling, and humanity. Couture here becomes narrative capital, symbolic capital, emotional equity, not a short-term revenue engine, but long-term cultural value.

Walking out of the Grand Palais into the grey Paris rain, what remains is not