Theera Chantasawat: A visionary redefining Thai weaving and design excellence

Author: Phuriwat Hirunrangsee | Photographer: Somkiat Kangsdalwirun and T-ra

Mar 13, 2025

What began as a simple social media post offering to help villagers develop community products has become a twenty-year journey for Theera.

"I was teaching at university, and during the long holiday break, I spontaneously posted on Facebook that any villagers wanting help developing products or weaving could message me. When I woke up the next morning, the post had hundreds of shares and messages. I knew a deputy governor of Phetchabun province, so I visited there first, and that's how it all began. The feedback was quite positive when we transformed traditional textiles into more contemporary pieces. After that, government agencies kept contacting me, and I thought this path suited me well since I connected easily with the villagers and enjoyed this lifestyle. It's been nearly 20 years now."

His initial intention in working with communities was to elevate community products' quality and design to increase their value.

"At first, I wanted to create sellable pieces. Previously, I might have been quite egotistical from my designer background. When I sent designs and patterns, they proved too difficult for the villagers to develop further. They typically used only one or two techniques in their dyeing or weaving. But when I visited, we started layering techniques to create new patterns. As it became more complex, we adopted the concept that OTOP items don't necessarily need to be cheap. Using more spectacular techniques allowed for higher pricing. The villagers were skeptical at first until we demonstrated it. We wanted to change their mindset about OTOP products, they're not just cheap items but craftwork. We took two approaches, making pieces that could sell quickly with simpler weaving and modern colour combinations, and creating more complex pieces ourselves. The feedback came directly from customers, and we discovered that Thai top spenders were willing to pay for intricate handwoven pieces. This made the work exciting, we wanted to see Thai craft develop beyond its current state."

His teachings began showing clear results as communities developed methods to maximise their resource utilisation.

"The villagers are fighters who need to survive. During COVID when the economy was down, we had to adapt our methods, not buying new materials but using existing stock, which aligned with upcycling principles. When I asked if they'd ever measured their silk thread stock, some had hundreds of kilograms, enough to weave hundreds of metres. Communities began realising that those sticking to old patterns might survive with existing customers, but those who didn't adapt and just copied others gradually disappeared. Products need a clear target market. When visiting communities, we don't impose our ideas but ask about their customers' age and demographics. If they're unsure, we suggest photographing buyers for analysis. This helps adapt to their concept, it's more important than thinking about inspiration or colour sources. Having a clear target market becomes the work inspiration."

His experiences in fashion industry allows him to transfer expertise into distinctive textile designs through close community collaboration.

"We focus on creating textiles using our concept of layered techniques. We tell communities that regardless of their method, making the fabric beautiful is the first priority, beautiful fabric can become anything beautiful. We maintain this concept in our fieldwork. If your weaving looks ordinary, it won't command a premium price. But with a concept and truly special techniques, they don't have to be complex, sometimes just colour combinations matter, everything must harmonise. It's not about personal preferences; it's about understanding your customer base's colour preferences. If the colour combinations stand out, we emphasise the craftsperson's strengths into techniques they excel at, never forcing anything that doesn't suit them. When we impose our ideas on entrepreneurs, they don't feel pride because it's our thinking. But when the women feel they've contributed their abilities, they can proudly say they chose the colours themselves, with some guidance from us. This makes work enjoyable for them."

From his decade-long experience working with communities, one particularly touching incident stands out.

"We felt this group had great potential - specifically Jum's Nitda brand's Mai Taem Mi in Chonnabot district. The Taem Mi technique reduces production time compared to the traditional mudmee technique, which takes much longer. Taem Mi is a hybrid, innovative technique they developed themselves. I designed patterns for them about 10 years ago, and the original patterns are still selling. They keep adapting, designing their own patterns, mixing elements, changing colours, and scaling patterns. We continue designing through Ms. Jum, the daughter. One day, during a Ministry of Finance project site visit, we met the mothers, about 50 weavers gathered to hear us speak, all around my mother's age. Before I began speaking, Ms. Jum's mother addressed everyone, saying they should pay respects to Teacher Tai for helping develop their skills until everyone's quality of life improved and they became prosperous. When she finished speaking, I was moved to tears. This was exactly what I hoped to achieve, seeing community growth, not just through our visits but through the advancement of all the mothers. When products sell well and people still request these patterns, it feels truly amazing. This is the kind of community work I want to do more of."

In his role as a teacher, he encourages the younger generation to use their knowledge of innovation in product development while instilling appreciation for Thailand's deeply rooted culture.

"I tell them that actually, they might be more skilled than me because they understand current trends much better. They know what's coming and going, what's popular. So I want them to look back and see that we have strong cultural roots. We need to utilise this advantage along with their abilities, like their knowledge of artificial intelligence, in design. Do whatever it takes to make products sellable and successful. Regarding innovation, we might not keep up, but the younger generation excels at it. One thing I constantly teach is that culture and innovation must go hand in hand. If either is missing, culture stagnates. Remember that innovation can change, adapting materials and ideas to combine with our vast cultural heritage. I believe that future generations will maintain interest in Thai handicrafts."

After his long-standing work with communities, this year marks a time when he will return to creating his own designs in a more accessible format.

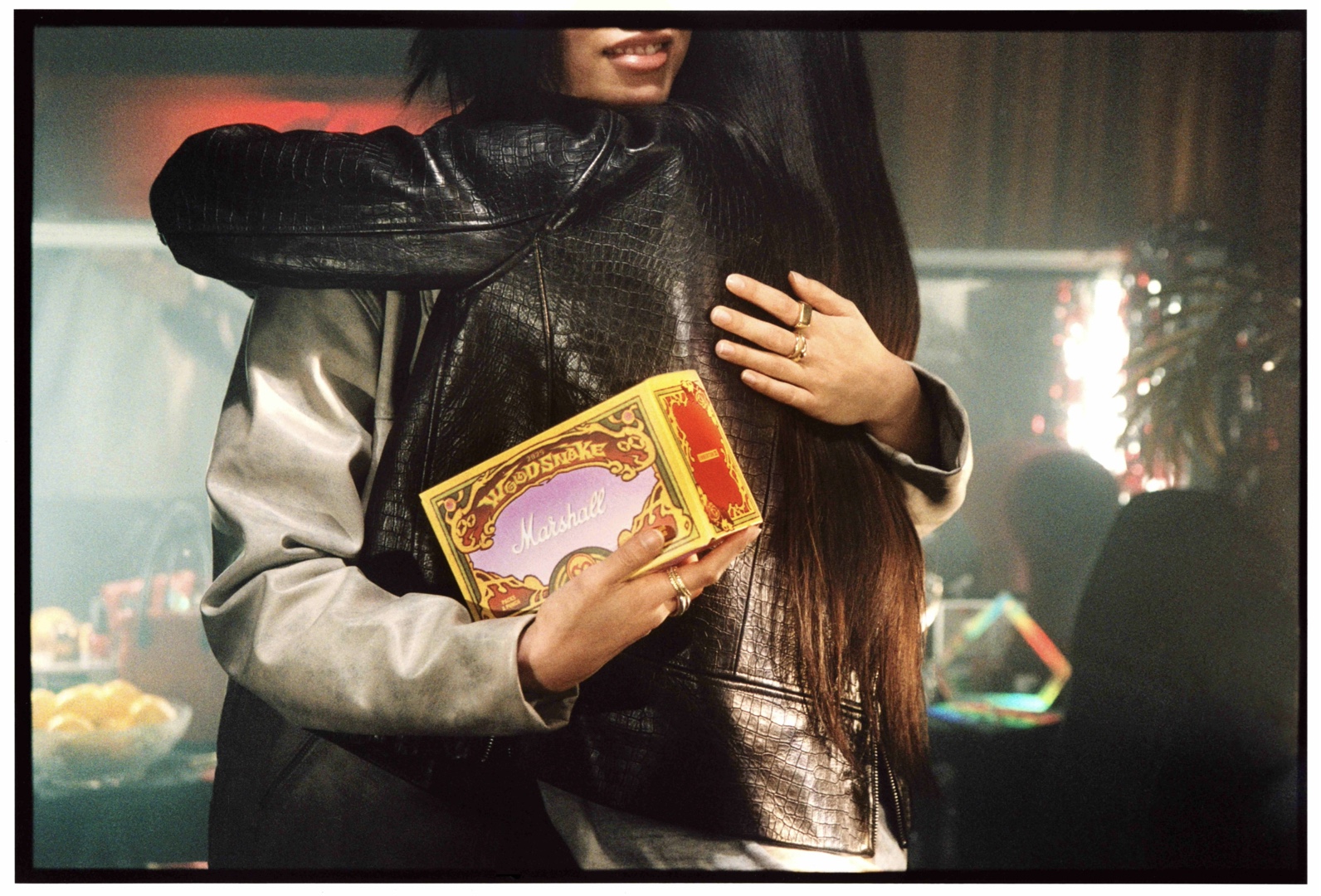

"It should start this year. When we visit communities and complete products, posting them on Facebook, everyone comments on their beauty and asks why we don't turn them into commercial products. This question has been asked for 10 years. Sometimes when we design for villagers and communities, we leave contact information for direct communication, but friends or acquaintances who follow up to buy often message back about inconsistent tailoring, differences from posted photos, or colour variations. These questions come constantly. My personal project is to create a brand using OTOP products in our style, selling them with complex designs and proper branding. While community projects will continue, as we enter our 20th year, we need to start focusing and being more selective. This might be the first year we begin focusing... If we look at T-ra from over 10 years ago, it had simple complexity, sounds contradictory. If we recreate T-ra in a new format, we might need to remove the draping because it's difficult to tailor, and some Thai fabrics like handwoven cotton aren't suitable for draping as they make clothes bulky. You might see new designs that are more streamlined, with better patterns and longer wearability."