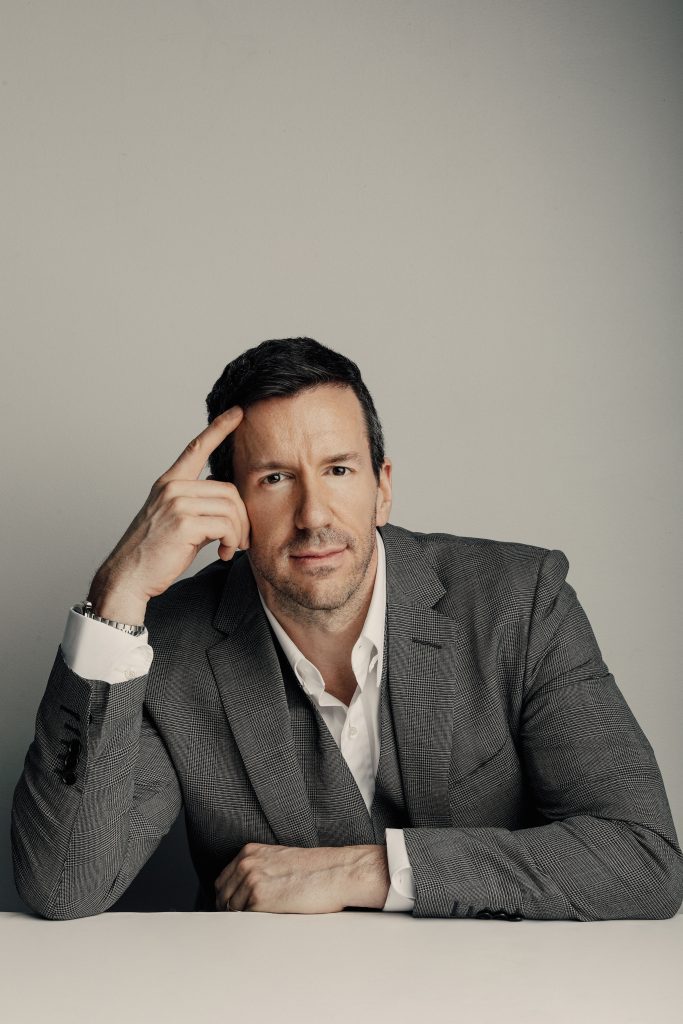

Silicon Valley veteran Alex Clark has a simple solution for the major problems of social media: give users control of their content. He tells Matthew Scott how – and why – his new platform QP does just that

Alex Clark doesn’t initially come across as a man who might be a disruptor. The Vancouver-based American is laid back and laughing as he explains how he wants to take the current social media universe and turn it on its ear.

It takes a little while before we get to the crux of Clark’s mission – through disarming and often self-deprecating tales of his impressive rise through the corporate ranks – and the mood shared across Zoom is so casual that it takes a few moments for the scope of Clark’s vision and his words to sink in.

“I kept thinking about social media and all these limitations and issues,” he says. “And I started thinking of messaging and social media as content distribution. Nobody’s holistically looked at where social media is going and said, ‘Wait a minute – you’re solving a piece of it but you’re not solving the whole thing.’ And that’s really what we’re looking to do. We want to give control back to the creators.”

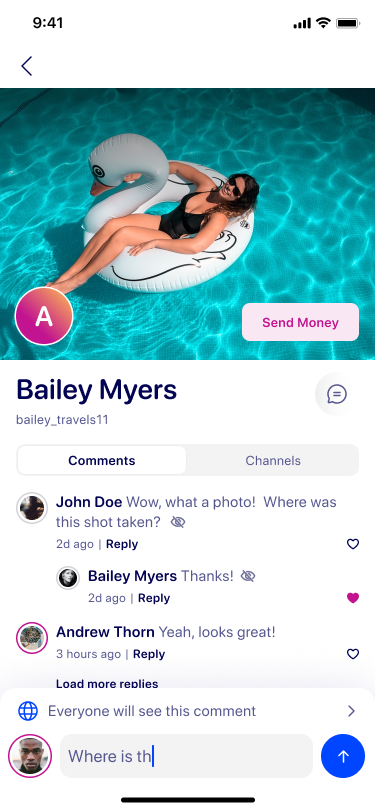

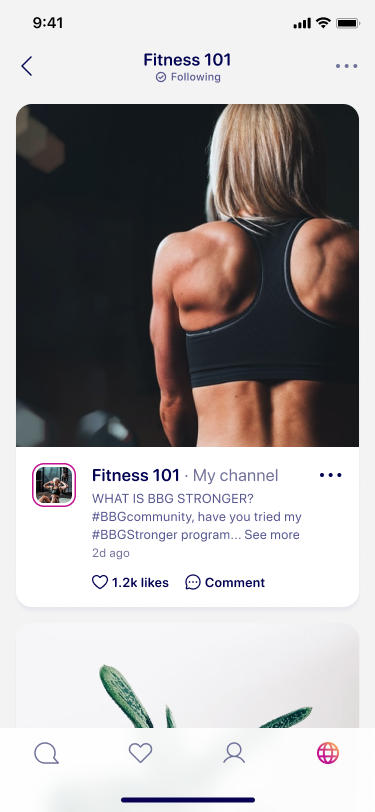

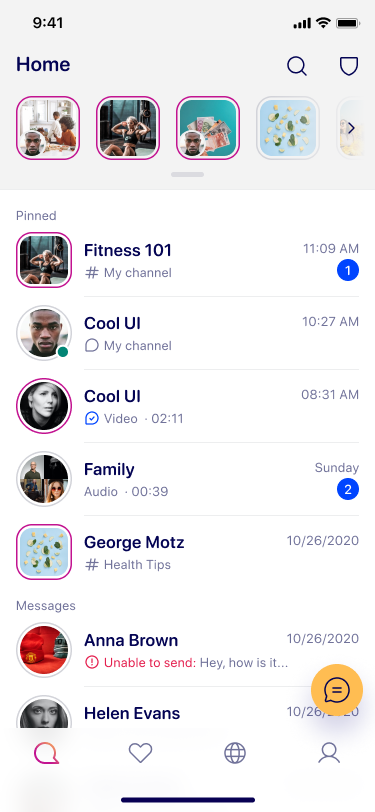

The Clark-led QP social media platform was set for launch at the end of October, after a registration period of a few months and a growing and global curiosity as to what this initiative was all about. Its mission statement reads that it is a platform built entirely for creators, who can control the flow of messages and content and, hopefully, money that their content generates. It allows for the creation of channels for images, videos and podcasts, and opens up accounts for donations or revenue through a premium subscription channel – with the proceeds split 90% for the creator, 10% for the platform – without dabbling in advertising.

The QP launch comes at a time where there are questions – increasingly – about what established platforms such as Facebook do with content, and revenue raised from it, and about such concerns as privacy and the use of personal data. Days (and nights) spent under the cloud of a global pandemic certainly seem to have encouraged these sorts of conversations, as for so long our lives have pretty much been lived online.

“There are these two major current trends,” Clark says. “One is ‘Get off Facebook’ and two is that, hey, the creator economy is now this really big thing. Covid didn’t create these trends, but it certainly accelerated what would have taken five years to something that has arrived instantly.”

Clark’s story started during Silicon Valley’s boom years of the 1990s. Having grown up in San Jose, California, he found himself immersed in the world of software technology as it rapidly evolved. But it still took time for the penny to drop when it came to the path his life should, and would, follow. At first there was an interest in animation, and drawing cartoons.

“But I had always played with computers,” he recalls. “Whenever you have a hobby that you’ve had since you were young, you never think you can make money from it, right? At the time Silicon Valley was booming like crazy, and I even noticed that cartoons were not being drawn by hand anymore, they were being computerised. I liked space and science and thought maybe I’d get into aerospace engineering, because then I could tell people at the bar that I was a rocket scientist and I thought that’d be cool. So I studied that for, like, three days. I dropped out because I kept getting people needing help with their software, and then it finally hit me. I was surrounded by the boom, I kind of loved it, and so software became my thing.”

“What I did was I started looking at not only value in the content that’s created, but value in the access to self, and treating knowledge as content that’s valuable”

– Alex Clark

The QP concept was first conceived after Clark had made his mark on the corporate world, and cashed in on the data integration platform Bit Stew Systems, which he co-founded, by selling it off to General Electric for US$153 million. Time without gainful employment soon became too much time to sit and think.

“For start-ups, your own company, you work so tirelessly that it’s almost an excuse to not look at your life and what you really want,” says Clark. “The work stops and you really have to ask those questions, the ontological questions. What is it I want to do in my life? What kind of person do I want to be? If I’m not defined by work, what am I defined by?

“I discovered I didn’t want to sit in a swimming pool, floating and drinking martinis all day. I did that for two years. And I also found that I still wanted to dodge all those big questions about my life – so I started a new company and went to work again.”

During his downtime, Clark had become fascinated by how easy it was for strangers to track him down via social media. That set him thinking about other platforms he was using – including WhatsApp, Instagram and WeChat – and immediately he saw some simple solutions to the problems, often self-inflicted, that have long plagued currently popular platforms. One was a need to hand users complete control over content – meaning the ability to edit messages (and even delete them) after they have been sent.

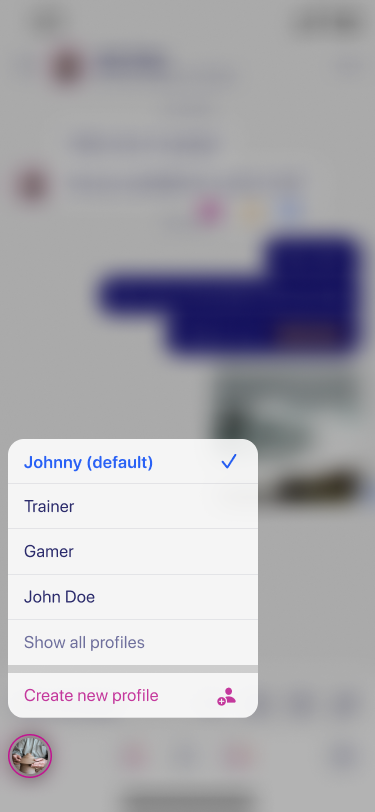

“If I’m using messaging for work and for personal, why can’t I set a profile for one person so I look professional and

another for my friends so I look casual?” poses Clark. “I really started thinking about it, and I kept asking why don’t I have control over my content? If I send a message to you, and it had a typo or it wasn’t meant for you or something

else, I can’t change it – you own it. You have control over my stuff. And so I thought, you know what, it’s backwards.

Why don’t I create a foundation where it’s different – I give you privacy, I give you control of your content.”

So what else is in it for us? There’s also the ability to schedule the sending of messages and content – ideal for those with family and friends living and working in different time zones. It was inspired by the early impressionable days of Clark’s relationship with his wife.

“I think I was on my couch at like 9:30 at night and I was so tired and wanted to go to bed, but we did this whole thing where we messaged each other good night. I didn’t want to be lame going to bed so early,” he recalls, laughing. “So I’m like, why can’t I schedule this for 12 so I look cool?”

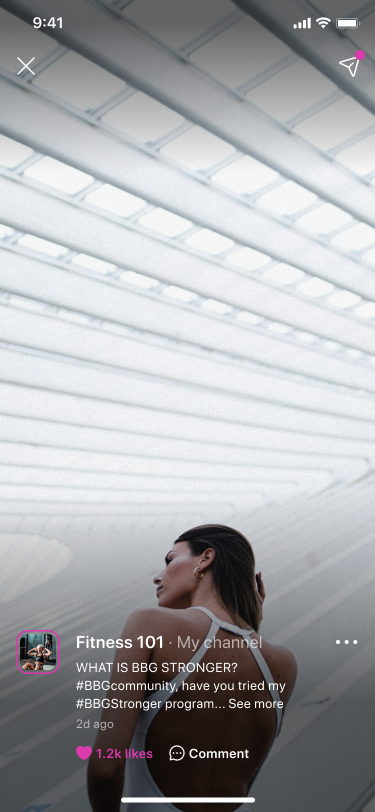

But the driving force behind QP is Clark’s desire to hand almost total control of content – and how it is used – to the creator. He provides a simple analogy of a fitness instructor who wants to post platform-exclusive workouts for US$10 a month but who can also offer personal training for US$500 a month.

“I can basically take my audience and monetise them directly, and curate and subdivide that audience. What I did was I started looking at not only value in the content that’s created, but value in the access to self, and treating

knowledge as content that’s valuable,” Clark explains. “And so the way we treat messaging and distribution is like a mix of WhatsApp and Instagram and WeChat all in one. We’ve taken the best of everything, leading with messaging first, but still giving people channels where they can post content so that subscribers can subscribe. It’s all pretty simple. What QP does is content distribution where you own your own content.”