The National Gallery stops in Hong Kong to show how classic art can inspire modern audiences

Feb 19, 2024

Featuring 52 of the world’s finest masterpieces and spanning more than 400 years of Western art history, the National Gallery, London’s travelling exhibition is making its third stop at the Hong Kong Palace Museum. Dr Gabriele Finaldi from the National Gallery and Dr Ingrid Yeung from Palace Museum speak to Zaneta Cheng about how art can encapsulate a period and provoke thought through curation for new audiences

The first painting visitors see when they walk into the Botticelli to Van Gogh: Masterpieces from the National Gallery, London exhibition at the Hong Kong Palace Museum is Red Boy, a portrait made in 1825 by Sir Thomas Lawrence. It’s one of the National Gallery’s newest acquisitions, bought by the museum in 2021 from a private collection for £9.3 million. “It’s a very famous picture. It was the first painting to appear on a UK postage stamp, so when the opportunity arose for us to acquire it from the descendants – really, because the picture has been in the same family ever since it was painted – we were quick to take up the offer,” says Dr Gabriele Finaldi, director of the National Gallery, when asked why the museum decided to acquire the painting two years prior.

“Secondly, any picture that comes into the collection has to meet a very high threshold of quality, state of conversation and what I call representativeness.” Representation is the strand that ties together all 52 paintings in the National Gallery’s travelling exhibition that will be shown at the West Kowloon Cultural District venue until April 11. Hong Kong is the last leg of the tour, after Shanghai and Seoul earlier in 2023, and coincides with the closure of one-third of the British gallery for renovations for the bicentenary of the museum. “For many people, seeing this exhibition will almost be a sort of crash course in the history of Western European painting and I hope that it encourages visitors to take greater interest,” says Finaldi.

The exhibition covers the range of the National Gallery’s collection from mediaeval Europe up to the early 20th century. “The gallery has a very strong Renaissance collection. So, how do we ensure that that’s properly represented? Well, you know, you’ve got some of the great masterpieces in the gallery such as Raphael’s Madonna and Child. You’ve got one of the Botticelli panels. You’ve also got the Antonello da Messina. While it may not be a name that people are so familiar with outside of Europe, nonetheless, it’s absolutely one of the great masterpieces in the gallery’s collection,” Finaldi explains. “When you look at the 17th century, you think of Rembrandt, you think of Velázquez. Well, those artists are represented in the show as well.

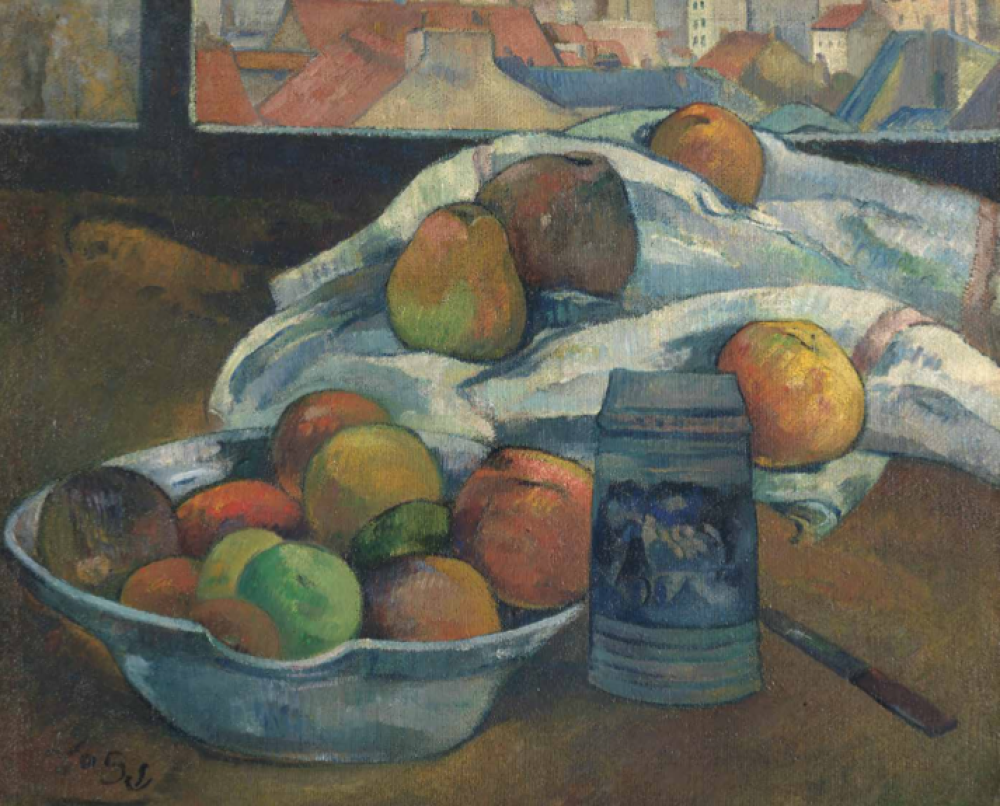

“When you get to landscape, you know the great landscape painter in this country is Turner, and Turner very interestingly looked back to the European tradition of Claude [Lorrain], the French 17th-century painter. He knew paintings by Claude that were in the National Gallery collection when he was painting and, of course, we were very keen to include some of the great 19th-century pictures – van Gogh and Monet, for example, are very strongly represented as is Cézanne, who later in life steps outside and does these great landscapes but a lot of his work is about thinking about the still life as a vehicle or

the studio interior as a vehicle for artistic experimentation and the painting we have certainly reflects it.”

As an institution, the National Gallery has played a formative role in the careers and lives and even afterlives of artists. This is most evident in the curation of Turner both in the gallery itself as well as the

Palace Museum’s exhibition. “Turner was intensely competitive,” Finaldi says. “He was competitive with his own contemporaries, Constable in particular, but he was also very competitive with the past. He looked back to the Dutch landscape painters of the 17th- century, particularly Claude Lorrain, and he wanted to compete with them and wanted to show that he could do what they did and even take it a step up. So interestingly, when he’s thinking about what to do with his legacy, he decides to give two pictures to the National Gallery on the condition that they always be shown for all eternity next to two paintings by Claude that he usually admired, which are sort of compositionally related, and we’ve maintained that in the National Gallery.

“In other words, we’ve got pictures which are 150 years apart being shown together and it’s about the inspiration of Claude and the response of Turner to Claude and that sort of internal dynamic where artists are looking back in time for inspiration – that’s something that continues very much today.”

The curation at the Palace Museum draws from this spirit. Whereas the other legs of the exhibition presented the collection in chronological order, Dr Ingrid Yeung, associate curator at the Hong Kong Palace Museum and curator of the special exhibition, decided to present the collection by theme. The image of the Red Boy leads into Sacred Images, a series of mediaeval and Renaissance pieces that then leads to Mythologies, Daily Life, Portraiture, Landscape and Modern Times, which include 19th-century Impressionist and post- Impressionist paintings. “These are actually classic themes in art history but what inspired me to arrange them in such a way is when I first saw the paintings of Mary and the Virgin and Child. I thought it would be very exciting for our visitors to see how the same subject was represented very differently over time,” Yeung explains.

Each of the paintings in the first section of the exhibition is set in its own alcove – an attempt by Yeung and her team to recreate the atmosphere of serene, spiritual contemplation within the space. “Man Kit, our designer, and I looked at a lot of reference images from all the greatest architects – from Le Corbusier to Tadao Ando. We were taking reference from the architectural greats,” she says with a laugh. One of the paintings closest to the entrance is Antonello da Messina’s painting of Saint Jerome in His Study, which depicts Saint Jerome in his study through a door frame. The door frame is enclosed within the picture frame, which is itself hung, inset into an alcove built by the Palace Museum team.

Also see: Art Central returns with new sector for new exhibitors and artists

“Dr Finaldi talked about how important this painting is. It’s because he’s the patron saint of knowledge and I think it sends a good message about the idea of the pursuit of knowledge. It’s one of the reasons why it’s important to begin with that painting and chronologically it also makes sense,” Yeung explains. “And the framing, it begins in our real space and goes all the way into these incredible details that is characteristic of early Netherlandish tradition even though Antonello was from southern Italy.

“I put Raphael and Sassoferrato next to one another very deliberately because Sassoferrato worshipped Raphael. But Sassoferrato’s image of the Virgin looking down with hands in prayer – I think when people tend to think of a religious image, something like this painting of his comes to mind even though very few people know the name Sassoferrato, right. But the image is one that’s proliferated over time and across the world so it’s a very powerful image and it’s Raphael-esque. Then if you look at the faces, they do that tenderness or that grace that we see both in the Sassoferrato and the Raphael. But then of course, Raphael and the Sassoferrato, is a product of his time. There’s that chiaroscuro – the very stark difference between the light and the dark and the intensity and emotional treatment of the colours. Reni is across from the Sassoferrato. Sassoferato also copied many of Reni’s works. So the visitor will see similarities in the treatment of light and shadow in both.

“Then there’s the Bellini, the master of early Venetian Renaissance who uses colour in the most masterful way. The lapis lazuli, ultramarine used to paint the blue robe – it’s a very different way of treating the Virgin and Child. So all of this thought went into putting the paintings together in this space.”

Yeung also pays homage to Turner’s desire to be placed next to Claude. In the last section of the exhibition, his work is placed on a four-faced column where Turner, Claude, Monet and Constable are each hung on a separate face of the column. The placement touches on Turner’s impact on the Impressionists – “especially their treatment of light and brushwork,” says Yeung. Turner and Constable are placed close to each other as competitive contemporaries but also because they “showed very different sides of the art movement that we call romanticism,” Yeung explains. Claude is placed next to Constable because “it was known that Constable said to his wife something like, ‘If there’s someone who can come between us, it would be Claude,’ which is why the three have been placed together.”

Touches of multimedia can be found across the exhibition. One is Damiano Mazza’s The Rape of Ganymede, which is the artist’s best-known painting. Presented against the wall, the oil on canvas was once a fresco and at the special exhibition, it’s beamed on the ceiling because “the original painting was octagonal and it’s a ceiling painting. I wanted visitors today to be able to experience that image, the way people were able to in the past.”

Another more playful instance is Vincent van Gogh’s Long Grass with Butterflies. Butterflies are beamed on the wall around the painting itself while light periodically transitions to yellow. “What we’ve done is to play with the lighting so that against the yellow, visitors may see more of the complementary colours in the painting – the violets, the blues and so on. The painting is against a green wall and it’s almost as if you can smell the freshness of the grass – the idea is to immerse the visitor in the long grass.”

Yeung and her team also added an educational wing at the end of the exhibition where visitors are shown how pigments were made (for example, ultramarine used to paint blues was once more expensive than gold during Renaissance Italy, the finest of which cost up to 100 times more than other pigments on the market) and the way paintings, using X-rays, were painted over, demonstrating the artist’s creative process. One example is the celebrated Red Boy, which was originally supposed to be Yellow Boy but Lawrence changed his mind halfway.

At the end of the day, Yeung hopes to stir emotions. “There are small paintings and these grand monumental paintings in this wonderful, extraordinary selection of 52 paintings. They really stir up all

kinds of emotions in the viewer. For me, at least, I hope people can look at some of the paintings, the exhibition design, the juxtapositions and so on – that they can look at them tenderly and look at them in awe. There are more intellectual, philosophical works that make you reflect on yourself. I think this propensity for self-reflection is something that art can enable. If there’s something powerful about art, I hope it’s that – the way that it can compel self-reflection.”