#culture / #art & design

Russian Painter Kazimir Malevich Questions the Legitimacy of Modern Painting

BY #legend

December 1, 2016

It is one of the 20th century art world’s most divisive works, yet in spite of its dynamism, it remains one of the least known. When it was unveiled 100 years ago in Moscow, it was regarded as the most disruptive canvas ever painted. In a world where Post-Impressionists, Cubists and Futurists were redefining how art was presented and viewed, along came Russian artist Kazimir Malevich and his revolutionary Black Square, which looked much like it sounded: a symmetrical shape in black, painted on a white background, with no apparent narrative, no point of reference, nothing pictorial, but which went beyond abstraction to the point of nihilism.

Black Square signalled either the death of painting as a meaningful art form, or foretold its liberation. Anti-art, anti-subject, anti-matter, anti-Mona Lisa, it blew apart the parameters limiting what a work of art could be, and how it could function in its culture. By far the most radical artistic revolution of the 20th century, it predated pop art by 50 years. Malevich and his achievements are still awesome, nearly 80 years after his death.

If you happen to be passing the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris, American architect Frank Gehry’s uplifting structure at the edge of the Jardin d’Acclimatation in the Bois de Boulogne, stop and look inside. There you will find Icons of Modern Art: The Shchukin Collection, an exhibition of visual dynamite, a sort of greatest hits of 20th century Western art, as seen through the eyes of one of its leading collectors at the turn of the last century, Russian businessman, philosopher and art historian, Sergei Shchukin. The exhibition is part of the programme for the Franco-Russian year of cultural tourism. The Hermitage Museum and Pushkin Museum contributed to the show, which comprises over 130 masterpieces by Impressionist, Post-impressionist and other artists, which Shchukin assembled into what has been called the most radical art collection of its era.

Shchukin was born in Moscow in 1851. His family had been manufacturers and merchants since the 18th century, Shchukin studied in Germany, Finland and St Petersburg. He lived in Moscow and Paris, and became acquainted with the work of Rodin, Huysmans, Degas and Renoir. He began collecting Impressionist works in 1897. Then a friend took him to see works by Monet at the Durand-Ruel gallery in Paris. After that, Shchukin never stopped collecting. He bought one of Cezanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire series, Van Gogh’s Arena at Arles and Gauguin’s The Fruit Harvest. Most famously, Shchukin commissioned two paintings by Matisse, Dance and Music, to adorn the stairway of the Trubetskoy Palace, Shchukin’s Moscow residence. Shchukin opened the palace to the public every Sunday, so that artists, students, critics and art lovers in Moscow could see the latest trends in modern art.

LVMH president Bernard Arnault appreciates how momentous the exhibition is. “It means assembling one of the most important collections from the early 20th century of masterpieces – from Picasso, Matisse, Gauguin – in a museum which is really the centre of the contemporary art movement in Paris,” Arnault says. “To see this collection, which is part of the treasure from museums in Russia, and to find it here in such contemporary architecture, the classical aspect of this foundation, is, to me, striking.”

The show is a moving experience, Arnault says. “There are so many masterpieces. It’s so inspiring that (the curator was telling me) when some visitors come to the rooms, some of them cry, they are so impressed. The emotion is so strong. Shchukin was really a visionary. He chose masterpieces which were not all recognised. He was criticised for choosing very modern paintings. He was nevertheless always seeing the future, and many artists of that time, many contemporary Russian artists of that time, got their inspiration from seeing such work, like Malevich and others.”

Malevich was born in Kiev in 1878. He became the leader of young Russian artists. He was always involved in the most daring pictorial experiments. Matisse, on discovering Malevich, visited Moscow and was awed by the depth of artistic talent in Russia. “It is not you who need to come to us to study, but it is we who need to learn from you,” Matisse said. Malevich had just painted The Woodcutter, one of his most beautiful paintings. He called the painting a “dynamic arrangement”, which turns his subject, a peasant, into a robot with aggressive volumes which seem to move. Malevich is interested in the relationship between pure shapes and their surrounding space, and seeks an internal tension that makes his paintings vibrate.

Malevich influenced fashion. He was a pioneer of geometric abstract art, and his work inspired fabrics decorated with geometric forms, rhythmically arranged, often creating illusions. He was a purveyor of rectangles and trapezoids. It’s tempting to sense traces of Malevich in the abstract work of Mondrian, and in the famous Yves Saint Laurent Mondrian dress of 1960. A contemporary and close friend of Malevich was the artist Natalia Gontcharova, whose work has strongly influenced designers such as Karl Lagerfeld. Gontcharova thought Malevich was far ahead of his time. “Here is an artist who skips steps in art evolution,” she said in 1915.

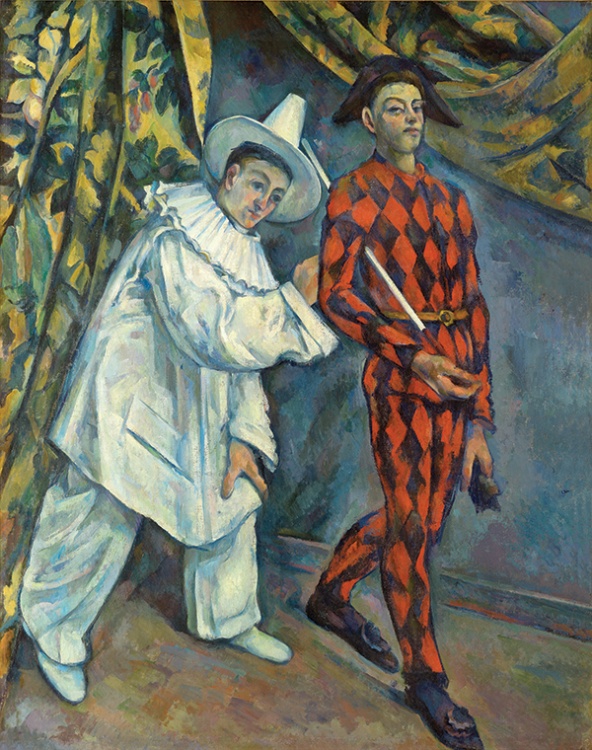

Malevich painted the first of the works that were to become characteristic of him in 1908. These early works are figurative paintings, in which individuals embody the great symbols of humanity. Many of the scenes he painted were inspired by rural life. Peasant Woman with Buckets and Child (1910) shows the monumental character of his figures. Taking in the Harvest (1911) shows the geometry of his planes and the contrasts among his colours. Both works are evidence that Malevich paid careful attention to old paintings, especially Byzantine icons, and to paintings by his contemporaries, such as Cezanne, Matisse, Mikhail Larionov and Gontcharova.

Then Malevich blew the contemporary art world apart with his Suprematist manifesto and 35 completely abstract works shown at the Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0.10 in St Petersburg in 1915. Among the notable paintings was Composition with the Mona Lisa, in which da Vinci’s subject appears as just one element of Malevich’s mosaic, but crossed out in red, with a black square above her. Malevich described the painting as “a partial eclipse” in his artistic development and as a cosmic entity, hinting at the direction Russian art was going in.

Another notable work in the 1915 exhibition was the one closest to no painting at all, Black Square. Malevich said at the time that the elementary contrast of black and white released a universal energy, and that all past, present and future paintings were summarised in this opposition and were consumed there. The public and the critics hated it. Malevich and his disciples consoled themselves by recalling that Manet and Cezanne had also been derided.

Malevich was far from bashful about Black Square’s contribution to culture. “The Square is a vivid and majestic newborn, the first step of pure creation in art, the face of the new art,” he said. “I went beyond zero, into creation, into Suprematism, the new pictorial realism. Before us stretches the abyss. Before us stretches infinity. Painting has long been outdated.” Long before the word pop was used to describe art, Malevich called Black Square a sort of “plastic realism”, saying it was plastic “precisely because the realism of hills, sky and water is missing.”

Malevich painted a utopian world of pure form and feeling, which had nothing in common with nature, using a universal language that may free the viewer from the constraints of the material world. The Impressionists, Cubists and Futurists created a new repertory of ways of expressing the modern world but, revolutionary as they were, none cast doubt upon the legitimacy of painting in the way that Malevich did. Those giants of art must have needed courage to push back the frontiers of their world. Standing even taller than those giants was Malevich, whose courage gave him the nerve to describe Black Square, as “the beginning of a new civilisation”.