As an expression, “Chinese food” is inadequate for the purpose of describing the culinary landscape of China.

Our vast country is hugely varied in its geography, climate and consequently its food. From the Tibetan plateau to the Yangtze basin to the coast, each county has its own dishes and distinctive flavours, yet China is thought to have just eight kinds of cuisine. Lu food, in the north, is known for its richness. The food of Anhui, Jiangsu and Zhejiang, in the east, is characterised by its sour flavours. Dishes from Guangdong and Fujian, in the south, are delicately sweet. The food from Hunan and Sichuan is numbingly spicy.

Yet author Kei Lum Chan says Chinese food falls into far more than eight categories. He says the country encompasses 34 provinces or regions and 56 indigenous nationalities, each with its own culinary tradition. In distinguishing one cuisine from another, flavour is important, but he says that just as important are the cooking techniques – including stir-frying, double steaming and braising.

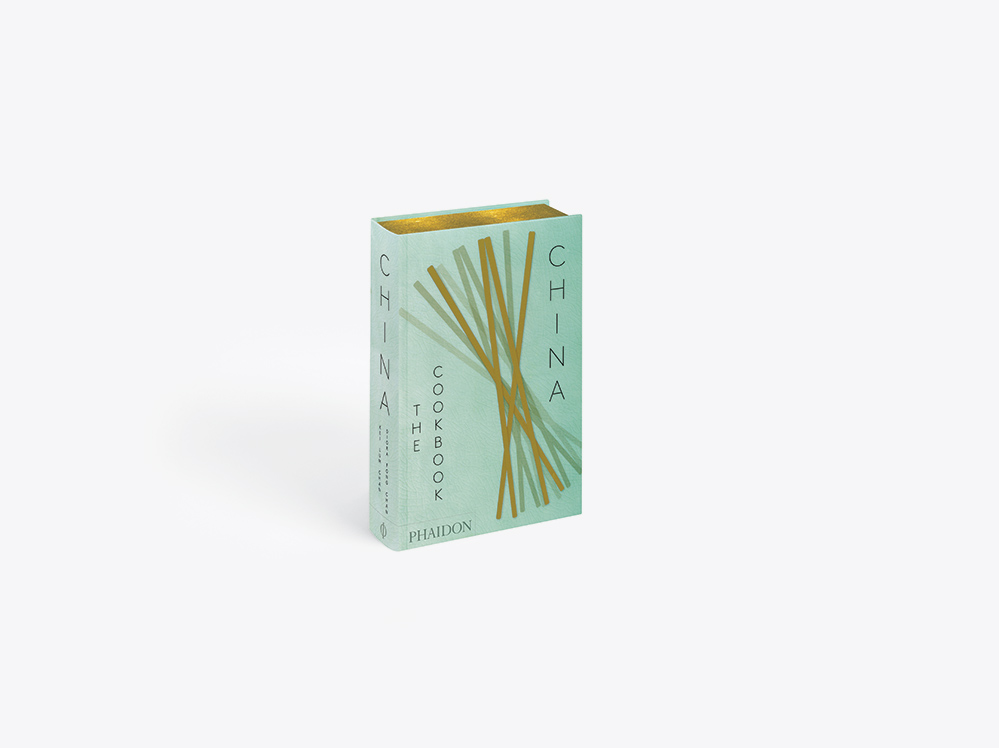

Chan and his wife, Diora Fong-Chan, have just published one of the most comprehensive tomes yet on Chinese food, China: The Cookbook. The 700 pages, edged with gold leaf, explain the history of Chinese cooking and contain 800 recipes. The authors are both renowned writers on food, having published more than a dozen cookbooks in Hong Kong and four in Taiwan. The pair are said to have an unrivalled knowledge of cuisines and cooking techniques, and are consultants to restaurant groups in Hong Kong and further afield.

China: The Cookbook is the first effort by Chan and Fong-Chan – or anybody else – to cover all kinds Chinese food in one publication. The extraordinary endeavour could not have been undertaken by anybody with fewer connections or a less refined appreciation of the cuisine.

Chan and Fong-Chan both come from families with a deep appreciation of fine food and culinary culture. Among Fong-Chan’s ancestors in the distant past were members of the Qing Dynasty court, and among those in the more recent past were holders of high positions in the government of the Republic of China, which was driven from the mainland in 1949. “We knew how to eat,” Fong-Chan says. “We had more chances to eat good food than the average person. We were very lucky.” Fong-Chan developed an uncommonly sensitive palate. Just a mouthful or two of a dish will reveal the ingredients to her.

“Diora has a very discriminating tongue,” says Chan. “She is able to tell just from eating a dish what’s in it, what’s wrong with it and what needs to be added. My father trained her even further.” Chan’s father was the revered Chan Mong Yan. Chan gives his father the credit for instilling in him much of his knowledge of Chinese food and his passion for it. Chan Mong Yan was a journalist and food critic prominent in the 1950s. He wrote Food Classics, published in 1953 and comprising 10 volumes. Food Classics is still regarded as the bible of Chinese food, yet it covers Cantonese dishes only.

READ MORE: An easy Chiu Chow recipe with Kei Lum Chan and Diora Fong-Chan

“In our book, we cover 33 regions and subregions,” Chan says. The challenge was not the writing, but the selection of examples of food suitable for the book.

“We had no trouble with the content,” he says. “In fact, we had so much material, the difficulty was how to select proper dishes, ones that represented the regions and subregions, and that were also suitable for home cooking in the Western world.”

It took two years to write China: The Cookbook but more than 20 years of research. The pair had acquired a mass of recipes even before they began. They travelled often, visiting friends, meeting locals, attending banquets, seeing what wet markets had to offer and generally sampling the food. Fong-Chan says making mental notes became a habit. “When we go home, we try to cook the dishes again,” she says. It may take a couple of tries, but the couple says they always manage to recreate what they taste on their travels.

They learned how to stuff freshwater dace with its own flesh, minced, and with mushrooms and dried shrimp, while maintaining the fish’s shape in Shunde. At sea off Chaozhou, they watched fishermen salt their catch in bamboo baskets and boil the fish in seawater to preserve its flesh. In Shanxi, where noodles are a much-loved staple, they learned to make the famous knife-cut noodles, holding a piece of dough in one hand and, with the other, deftly slicing off strips directly into a pot of boiling water.

The couple love cooking and eating, but have never been enamoured of running their own restaurant. “We’ve opened restaurants three times,” Fong-Chan says. “But it was a lot of hard work, so we gave up.” They prefer to teach the culinary arts through their books and cooking classes. “We teach other people to cook so they can open restaurants and we can go and eat,” says Chan.