Sitting in Massimo De Carlo gallery with Hong Kong artist Lee Kit on the eve of his most recent solo exhibition, Something You Can’t Leave Behind, the conversation takes a surprising turn. “My favourite classical artist is Jan Vermeer,” he says. “I will travel to see Vermeer’s paintings.” He explains his rationale: “In high school, you only get to see a few artists: Picasso, Van Gogh, Constable landscapes… I looked at Vermeer – making very, very beautiful but very boring things – and I thought, ‘I love it’.”

This revelation surprises for two reasons. First off, it seems an unexpected imaginative leap from the contemporary “asylum white” art space in which we’re talking. Second is what preceded it, Lee discussing a work on the wall that bears the letters: “you, f***, you”. How to read such a work of art, this writer had asked, in a world where the copulative expletive has been so relentlessly invoked?

“For me, it’s muted,” he says, smiling. “There is no ‘sound’ for this painting. But it was from a song title by a Hong Kong band from London, Of course it could easily be understood in different ways in Hong Kong.” And also on a personal level, he explains. “Sometimes it doesn’t mean anything when I say ‘f*** you’. You can say ‘f*** you’ to your partner the same way you say ‘I love you’. For this one, ‘f*** you’ is too mute. It means nothing. It’s too light. It could be three words. If we read it as a sentence and try to understand it, and try to think about why, it’s not about the painting or what we are thinking about. I’m not trying to find a reason to justify it.”

This exhibition marks Lee’s first in Massimo De Carlo’s Hong Kong space in the On Pedder building, following last year’s exhibition He Knows Me in the gallery’s London space. In addition to the exhibitions, his solo project It Was a Cinema was presented at Massimo De Carlo’s booth in the Kabinett section of Art Basel 2017. Lee also took part in the 55th Venice Biennale.

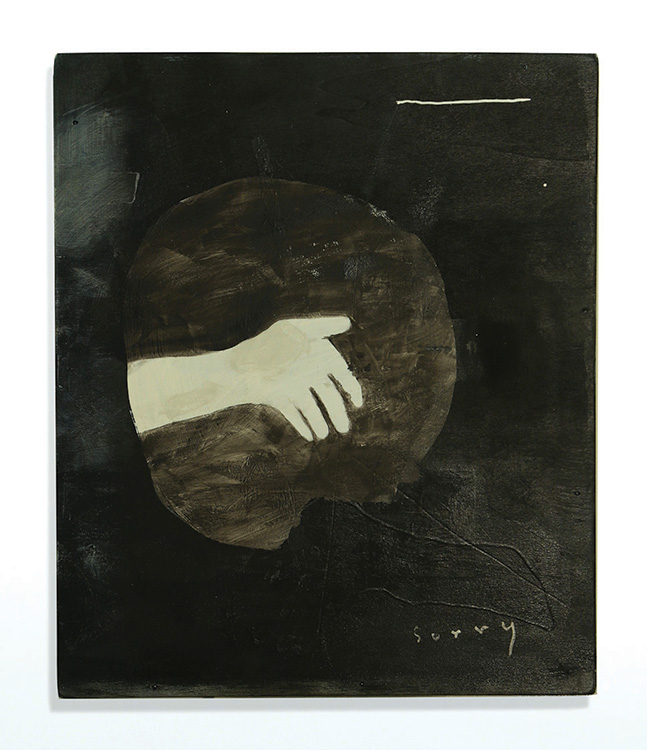

The artist’s practice has been deeply rooted in his personal surroundings and daily experiences. Through a wide array of mediums that include painting, drawing, video and installations, he explores the human sphere of emotions. Now splitting his time between Taipei and Hong Kong, Lee shares his latest reflections and thoughts through his new collection. By examining the habits and traces that compose our daily lives, he engrosses the viewers into a cryptic yet intimate experience.

Lee has made prolific progress in a finance-driven city where art is never an obvious career choice. “Honestly, when I look back, I didn’t even want to be an artist,” says Lee, as the revelations continue apace, all with a wry smile and in good humour. So what would he rather have done? “When I was young, I was very good at earning money. Because of my family burden, I had to earn money. I was a worker and DJ in a bar. That was in Mong Kok and it was the early 1990s. I was a construction worker on a construction site. I was a designer. I was a teacher. I didn’t want to be an artist.” But he so happened to excel. “I was good at art. I studied art but I didn’t want to be a professional artist because I didn’t know what a professional artist was or what it meant.”

He isn’t a political artist, per se, but Lee attracted a great deal of attention when he moved to Taipei in 2012. Why did he feel the need? “I was angry in 2012 because of the political situation in Hong Kong,” he says, noting the fact but then drawing on practical considerations for the decision. “If I really want to make a painting, I need distance, otherwise I cannot see the painting. Painting is very simple; you need a certain distance. If you’re working on a small canvas, you need distance, and bigger canvases need even more. So I thought I should move somewhere else.”

Initially he thought of Berlin, but felt it too far and plumped for Taiwan. “Also, of course, because I love Chinese culture,” he says. “I moved there with a small suitcase. I called a friend and asked if I could stay. For me, Taiwan is a good choice. I didn’t move there. I just had a small suitcase with me.”

As lightly as he travels, our conversation hops and skips between topics at some speed. His favourite book is One Hundred Years of Solitude, by Gabriel García Márquez, but he also loves the short stories of American writer Raymond Chandler, whose books he can read “all the time”. He Facebooks, but reluctantly. “I don’t really like it because it’s also a kind of brainwashing.”

He talks of Hong Kong being a city where everyone loves money but in which its artists are “anti-making money”. And of art now being part of “the entertainment system” and taking greater control of his own creative destiny. “Maybe I want to do things apart from art,” he muses. “Something for the people. I want to show something that people don’t know me for.” Lee’s never been very “present” in a Jeff Koonsian art way, so that admission runs counter to his more elusive persona. “I never contacted socialites. I never contacted curators or did promotions, or approached people for exhibitions or funding,” he says proudly, as if to remind me of his “brand” and its organically grown power.

Then we’re back to Vermeer – and the love still shows. “Vermeer painted very natural things,” says Lee. “When I first started travelling, I saw his paintings and noticed something: I started to cry when looking at his paintings. Then I understood. And at that point, I can say I really loved this artist’s work much more than any other artist’s work. Then I started to realise we had similarities. For example, he always has a map at the back of his paintings. His sense of lighting is similar, something very banal. The things in life that we paint… we like similar things.

“I learned something from his paintings: sincerity. It’s not common now. I think sincerity is very important. As an artist, if you cannot be sincere, you cannot be honest. If you’re honest but not sincere, it doesn’t mean anything.”

And with that, he’s gone.

This article originally ran in the July 2017 issue of #legend magazine.