Last June, English watchmaker Peter Speake-Marin announced that he was leaving his eponymous watch brand to start a mysterious new venture. Three months later, he informed the world of his next step: an educational website, with the titillating title The Naked Watchmaker.

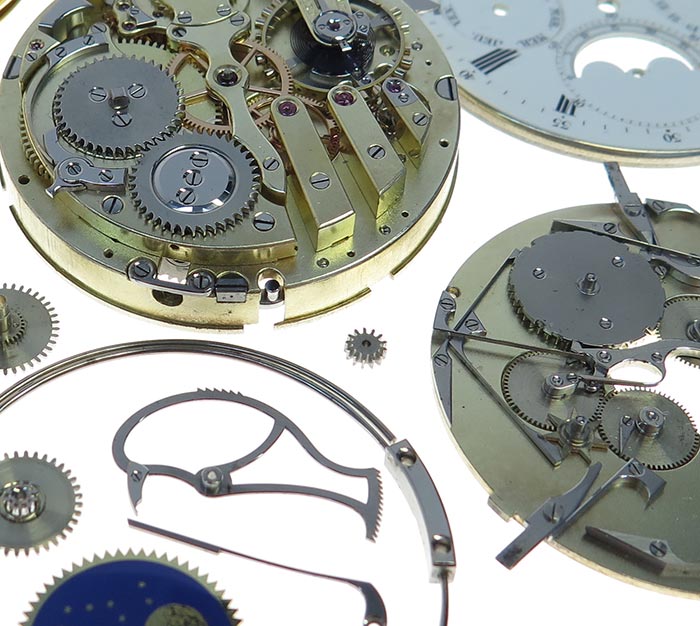

Speake-Marin has no regrets about stepping away from the brand he spent 17 years building, telling me, “Life is short, and we should follow the goals we make for ourselves and the dreams we have.” His dream was to share his love and knowledge of watchmaking to the world through a different medium. Instead of creating timepieces, he wanted to take them apart. In the process, he would photograph each individual component and then write a detailed analysis of the deconstructed objects.

It’s a bold move, of course – there’s no one else in the world singlehandedly taking on the task of building this horological encyclopaedia – but he thinks the tools are there and the time is right. Few people genuinely care about sharing out of passion rather than commercial gains, and Speake-Marin is one of those rare individuals.

We caught up with him last month as he was about to give a lecture at the Horological Society of New York, and had the chance to talk about new developments on the project as well as his insights into the state of today’s watch industry.

How did you become a watchmaker?

I started at London’s Hackney Technical College in 1985, followed by WOSTEP [the Watchmakers of Switzerland Training and Educational Programme] in Neuchatel in 1997. Then it was a series of jobs in after-sales service for modern brands including Piaget and Rolex, before spending six years in restoration in London’s Piccadilly.

What is your overall vision for The Naked Watchmaker?

The goal is to present a view of horology in a unique and original way – the history of watchmaking through to the present day – so that people young and old can develop a holistic view of this subject. It’s built on the products that have been made and the people that have made them – avoiding the marketing storytelling that I believe people are tired of. The feedback I’ve received over the last four months has now convinced me that this approach is not only aligned with the present moment, but is very welcomed by people in general.

You take all the macro-photography on your website. How did you pick up photography? What gear do you use?

I have been photographing watches since my time in London more than 20 years ago; before digital photography, I was using medium-format Mamiya. Today, the new technology makes the job an easy one; the most challenging aspect is always the lighting. But I love the process, which makes the job a pleasure rather than a chore. I use Canon cameras, both a small G16 and a larger D77 with a 60mm macro lens.

Will you be including more videos on the website in the future?

In the future, there will be many videos, both in partnership with WatchesTV – our first has now been launched – as well as those that I make on my own. I also have ideas for documentaries that cover different elements of watchmaking, present and past.

What are your thoughts on watch fairs like SIHH and Baselworld? Are they less significant today in the digital era or are they still important events on the watch calendar?

Hands-on experience, being able to touch the final product in the metal, will always remain important – in the same way that retail shops are essential, especially for high-value products. Today, we see a significant decline in both the retail and exhibition spaces, but it will always exist on some level. In recent years, there has simply been forced and unrealistic growth in this segment, and it will reduce to a more organic and intelligent size.

In your interview series, you interviewed Maximilian Büsser, the founder of MB&F, who said that big players dare not invest in creativity and that there will be two kinds of watchmaking in the future. How much do you agree with that sentiment?

Large companies need to be “safe” to assure the large volume of figures they need to maintain their future, which means appealing to broad groups of people. This often means that real, creative originality is stifled because it is, in essence, dangerous. This is not a criticism, but a logical reality – and why independent companies like MB&F find a place in the market, because what they do differentiates themselves from other larger brands.

Do you think there’s too much marketing and not enough educating in today’s world?

It’s not that there’s too much marketing, but how it is executed and the change in culture of the new generations who are born into social media, and all that in turn encompasses. We are in fact living in a period where there is more education than ever before and more access to it on every level. But also, we all know today when we are being sold to – and we are tired of it.

What are some common mistakes you see watch companies making when it comes to putting out their products today?

The fundamental error is a misunderstanding of who the client actually is and what they want, linked with an assumption that the client is either naive or uneducated. Knowledge is more prolific than ever before and people who are curious have much at their fingertips to learn about the products they want. The only problem is that there is too much material in circulation and much of it is distorted.

What are your own thoughts on where the industry will be in 10 years?

Watchmaking will exist as long as people exist. Horology is ultimately part of our culture, in the same way as art. How it will exist is another question. There will always be big brands, some independents will change category and become the precedent, and new companies will be born along the route, which will be as a result of new technologies. Some old mainstream brands will disappear as well, no doubt. Nothing remains the same in business as in life. The industry is a child – having died in the ’70s and being reborn in the ’90s – and continually changes, growing through its successes and failures, much like any organism or human being. Watchmaking and the business of watchmaking is in fact an art and not a science. And as such, it’s unpredictable and will always surprise us if we look close enough.