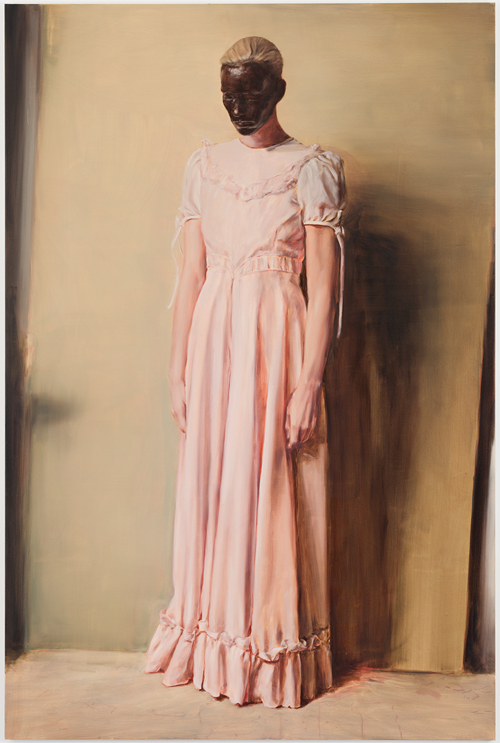

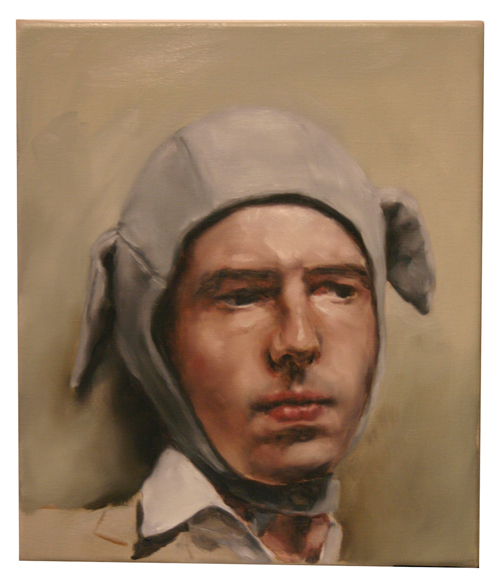

Michaël Borremans has a signature distinction: he’s a contemporary artist in possession of the talents of an Old Master, who divides the opinion of the art world like no other. His masterly technique prettifies, classicises and sometimes distracts from what many see as an undercurrent of the sinister, including dismembered and depersonalised subjects that stare through the observer or look at us not at all.

When I reach him at his studio in Ghent, Belgium, I find he’s hard at work on paintings for Art Basel in Hong Kong, before saying he “needs another 30 minutes” before we can speak. He’s mild-mannered about it, almost apologetic, but one harbours visions of Borremans sharpening blades in the basement of his studio. For good measure, he may need to uncork a nice Chianti, appraising a masterful Goya as he waits for the wine to breathe, like a modern Hephaestus in Hannibal’s lair and I’m the dial-in dinner. I call 37 minutes later, hoping the deed is done. “I was working on something when you called which I hadn’t finished,” he explains. “You haven’t done anything wrong…you’re lucky.”

Borremans may lack the commercial brand of British artrepreneur Damien Hirst, and the “artoon” commodification of American Jeff Koons but he’s still got the world’s most influential dealer to please. “I made a promise to David,” says Borremans, referring to leading art dealer David Zwirner whose clique includes luminaries such as Belgian Luc Tuymans and Germany’s Neo Rauch. Zwirner has represented Borremans from New York since 2001.

Last October, Sotheby’s sold Borremans’ Girl With Duck for €2.75 million, a record price for the artist’s work. “Now I have to deliver. So…I’m getting there, but it’s really a close shave. I’m very stressed.”

And yet the 52-year-old Borremans couldn’t sound any calmer, a duality not unlike his paintings that portray figures in states of anxiety and anonymity bordering on disturbing with brushstrokes as deft, precise and deeply rendered as Diego Velázquez, an artist whose “emotional and sensual work” Borremans reveres and has emulated.

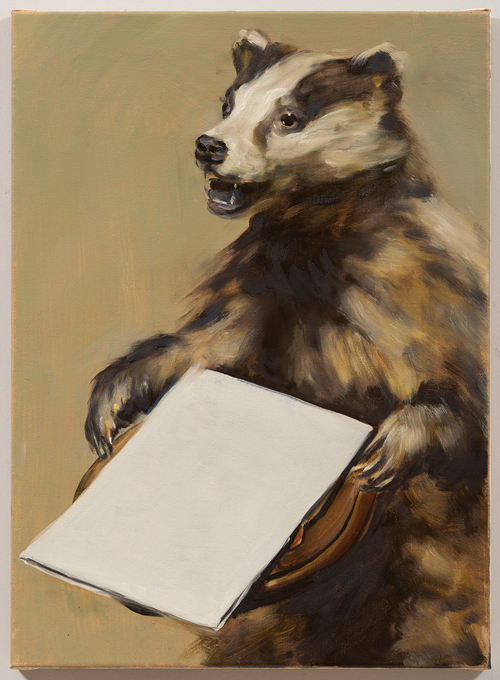

At least the observer knows what’s happening when looking at Velázquez; there is a discernible narrative. Not so Borremans, who denies his viewers context. There’s nothing warm or sweet here, and we’re often unsure if the real or the imaginary is being portrayed. These solemn, sometimes playful, moods feel incredibly topical and timeless, and the lack of context and detail delivers the psychologically charged atmosphere in much of his work. He’s firmly aware of the effect his modern duality creates.

“Viewers of my work, lovers or haters, all make the same mistake,” he says. “And I must be doing something wrong as a result. My work is very conceptual, reflects on many things and its value lies in its complexity. But some people don’t like it because it’s nicely painted and some people do like it because it’s nicely painted. Maybe I should stop painting in a nice way.”

Borremans paints in three studios and I suggest he should have a fourth to house an alter ego. “Maybe I’m schizophrenic,” he says. “I go from one studio to another, working differently in each. Different types of art make me want to work in different ways, so I try to arrange it that way and it works for me. It’s really nice. But if I tire of my studio, I go to another and I feel fresh again.”

His latest studio is a 45-minute drive from his home and he professes to be more reflective and calm in it. “It’s very new and I’m very happy with it. It’s woods and meadows, another lifestyle. In the morning I can take a walk and talk to the cows. It’s a very different style.

“It’s interesting to think about the production of the work, and how I can improve what I want to express. I know I can do a better job. Some people get it and some don’t. And it brings these very strange associations, the fact my work looks old school. But paint handling, that’s a nice extra about the work.”

Which leaves him and the future of painting where in the digital age? “Painting has nothing much to do with that,” he says. “That’s the value of it. That’s why paintings make money at auction and it has become more of an investment object. Now it’s getting worse and worse because the artworks are getting so expensive, the canvases have to be worth it. That’s an interesting phenomenon.”

But he concedes we may be reaching a tipping point when it comes to appreciation of such work. “I am an inventor of images and compositions, communicated through digital media, but the viewer knows he’s looking at painting which is an non-transparent medium. For now, a painting is still a painting. There is demystification going on there too, if you start to analyse the question. It needs study I think.”

We discuss Instagram and art, how some photographers shoot images deliberately to solicit instant “likeability”. Despite being a painter, does The Instagram Syndrome play on Borremans’ mind when creating for a show such as Art Basel in Hong Kong? Does he think like a musician pumping out greatest hits?

“It does if I do a show, but for an art fair it’s hard,” he says matter-of-factly. Art fairs are noisy, colourful affairs with everybody wanting to attract attention and some works require intimacy and silence to be appreciated. “I know which will work better at a fair and which won’t, but I never work with the intention of, ‘Now I’m going to make a work for that fair’. I can do that for a gallery show, then you make a group of works that work together and you create an ensemble, thinking how it will work in the space. That’s very conscious.”

Does he collect art? “I don’t follow that much what’s happening in the art world. My interest is rather limited. And there is so much information with the Internet, I deliberately limit the amount of information I get, otherwise it would drive me crazy. I look at my email once a week. Any more and I start to panic. I’m an artist, each time I look at art it is only to be inspired. That’s the only thing that interests me.”

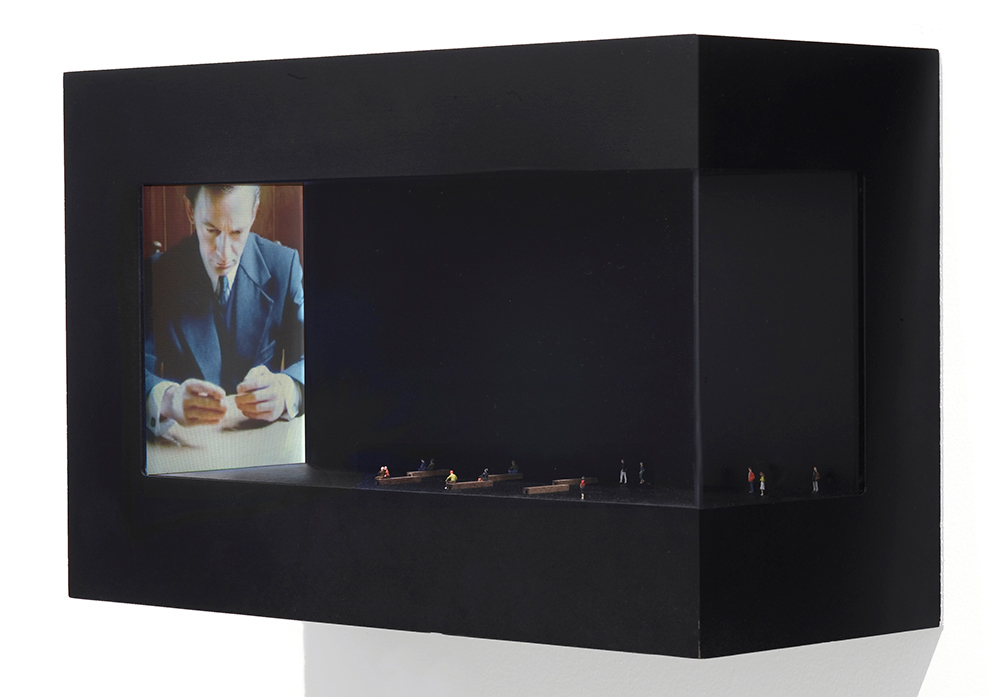

Borremans is a draftsman, has been in a band and likes heavy metal. He trained to be an architect, an engraver, an etcher, sculptor, photographer and filmmaker who started painting at the comparatively late age of 33. Critics say he has Alfred Hitchcock’s knack for creating suspense and suspicion, and that he uses technique to make even his most banausic work spellbinding, leaving viewers feeling that we have arrived a moment too early or late to understand the context of his canvases. Other critics say his canvases appear cinema-like and timeless.

“When I work in film it has to be mute. It has to be a moving image only. Music is easy, but if the film is strong enough, it doesn’t need sound and it can be more hypnotising. I like that. I like mute moving images, for my own work.”

The Angel is a work admired by filmmaker David Lynch. He says it offers a rare moment to delve into Borremans’ artistic and thematic process. “Personally…this is a special world, it’s The Angel, very personal.

I wanted my own personal angel. I was going through a certain period in my life, wanted to go to another phase and had to paint that image to do that. I hope it’s more universal than that.” Borremans made three attempts at The Angel. He threw away the first, kept the second and discarded the third. Completed in one week, he says he painted “in a very high state of concentration, almost like a trance” and didn’t leave the studio. Although pleased with the result, he dismissively calls it a soft, mellow work, in a comment that suggests he’s revealed too much of himself.

“I don’t consider it work anymore,” he says. “I want to paint like I’m an aristocrat in a room, and stylishly move about in the studio doing some genius paint-strokes and drink a cup of tea, or a glass of wine, in the meanwhile, very pleasantly, cool and stylish. If I do that and get in that mindset, I never do anything wrong in a painting. I become really good. If I try too hard, the painting fails. I can never push it too much. The more I enjoy it, the better I paint.”

No art hangs in Borremans house or his studio, apart from his own. “If I want art in the house, I just take the lid off the shoebox, put it on the wall and enjoy it very much.” It’s not a joke, he insists. “I actually do that. It’s very minimal and it doesn’t have to cost anything. Sometimes if I find a nice piece of paper I will put it on the wall and enjoy it the way it is.”

And then the scoop: he’s working on some sculptures in a deviation into a new realm. “They are derived and related to the drawings I do but, of course, they are new. It’s a more in-depth atmosphere and I think I need some more years to develop it. There are large ones, small ones, scale models, but I have a lot of fun doing that. I make money from my paintings, and the rest, like sculpture, can be a pleasure.”

With all of his creative interests and outlets, Borremans comes across as a latter-day Renaissance Man. “I’m mostly painter, and originally a draughtsman. As a musician I’m an amateur, but I’m a very bad swimmer and I can’t dance. Fifty minutes is my limit in the pool,” he says.

Humour. It’s not been a discussion topic but I tell Borremans I feel its presence throughout his work. “Thank you. I take that as a compliment,” he says. “Humour in art, literature, music, even a hint, adds a necessary ingredient that’s personal. There’s an element of needing to take things lighter and with absurdity. It’s a glorious, fantastic thing, humour.”

I know Borremans recently traded his Mercedes-Benz station wagon for a dark red E-type Jaguar. I ask if he’s Secret Agent 007 or if Ian Fleming features on his list of desert island reads.

“That would be Lolita by Nabokov,” he says declaratively. “It’s the most intelligently written book I have ever read. Nabokov’s style of writing is so subtle and smart and enjoyable. And the theme, even now it’s incredibly daring.

“To be so open about something like that. I’ve read other works of his but this is my favourite. I am now trying Pnin. It’s also interesting. I discovered Nabokov rather late in life.”

As much as books may be part of his process, he confesses to taking inspiration from film. “In my 20s, I watched so many movies, especially old black and white ones. I liked the whole atmosphere. I even used to record the sound to a cassette just to have it at home to repeat the dialogue”.

“One of my favourite film scenes is a French one with Jean Gabin. It’s called Touchez Pas Au Grisbi (Hands Off the Loot, 1954) a gangster film. Certain parts are really beautiful, almost uncut. I’m sure film school wouldn’t encourage that as it’s against all the rules of cinema. You see Gabin and his companion in an apartment preparing for the night. It takes about 10 or 15 minutes. You see them brushing their teeth, putting on their pyjamas. They have nothing to say to each other. He smokes a cigarette, puts it in the ashtray, turns off the light and goes to sleep. It seems to be very boring but it’s one of my favourite scenes.

“There’s not a word in it, it has no function. It becomes very odd, very strange. It’s unexpected and absurd.”

And it seems very much like Borremans himself.