Back to the Future with Daniel Arsham

Feb 04, 2020

New York-based artist Daniel Arsham works across a variety of disciplines, with each project more fascinating than the next. In Singapore for a group exhibition, Payal Uttam catches up with this future-forward trendsetter.

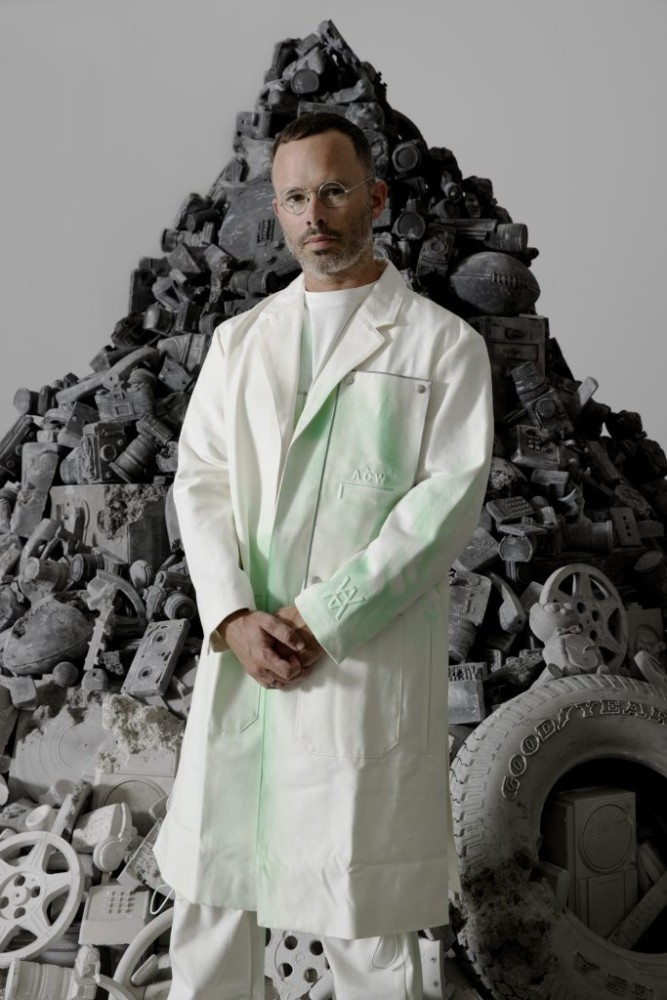

It’s Saturday morning and American artist Daniel Arsham is sipping coffee in the ornate, heavily scented interior of Singaporean watch boutique The Hour Glass. He’s dressed stylishly in faded jeans, a white T-shirt featuring one of his sketches, a personalised Porsche jacket and a beige New York Yankees baseball cap. On his wrist is a diamond bracelet and his Dior saddle bag rests on the sofa beside him. Something of a celebrity who straddles multiple worlds of art, design and fashion, Arsham is as perfectly at ease collaborating with a luxury watch brand as he is with exhibiting in a blue-chip gallery.

The 39-year-old artist is best known for his highly-Instagrammable crystallised sculptures of objects including basketballs, Ferraris, Leica cameras and boom boxes. Often styling himself as a fashionable archaeologist from an imagined future, Arsham describes these evocative, decaying objects as future relics – items from our era that appear as if they were unearthed thousands of years from now.

Over time, his work has caught the eye of numerous celebrities including Usher, Pharrell Williams, Swizz Beatz and James Franco – he’s collaborated with them and counts many as friends. These projects have included remaking Pharrell’s first Casio MT-500 keyboard in volcanic ash, crushed glass and crystal, and casting Franco as a lone laboratory worker in a series of films set in a dystopian future.

Today, Arsham’s oeuvre spans sculpture, installation, set design, fashion, film, furniture and performance. He’s made a name for himself among luxury brands, working with the likes of Dior, Louis Vuitton and Rimowa. He also runs Snarkitecture, a design and architecture practice with his friend, architect Alex Mustonen. They’re known for out-of-the-box projects, like creating a giant ball pit for adults or covering a fashion runway with hundreds of pounds of white confetti.

For the group show Then Now Beyond in Singapore, which also featured works by Marc Newson, Nendo and Studio Wieki Somers, Arsham showed a rotating installation of eight glistening bronze hourglasses set on a circular platform. He cracked open each one of the hourglasses and placed either a bronze camera or clock with an aged patina inside the bottom bulb.

Ahead of the exhibition opening, we sat down with the artist to find out why he’s obsessed with the future, what he’s doing to save the planet and how he has managed to cultivate 600,000 followers on Instagram.

How did you know you wanted to become an artist?

My grandfather was an amateur photographer and he gave me a camera early on. Cameras and photography were a big part of my early art-making. I was really interested in architecture. I can remember trying to reconstruct the house we lived in through drawings, like trying to make a floor plan at age nine or 10. I thought at some point I would study architecture and go in that direction, but I ended up going to art school and things went from there.

As a young artist fresh out of school, you worked on sets for the famed dancer and choreographer Merce Cunningham. How did that influence you?

He could create a piece that could be an hour long, but in some cases it would feel much shorter than that and in some cases it would feel much longer. That ability to pull and stretch time, I think, was a huge factor in the way people experienced his work – and something certainly that I took from him, as my works are able to collapse time in a certain way.

You describe almost all your works as objects from an imagined future. How did you become so obsessed with time and the future?

I always loved science fiction and movies that dealt with time travel. I think escaping a particular moment, being able to see something that hasn’t yet happened, or even travel back in time and experience an era before was always fascinating to me. In my early paintings, I created scenarios that didn’t include people in them, which allowed them to float in time; they could be in the future or the past. I felt people would lock the images in a particular time because of how they were dressed or how their hair was cut. That was 20 years ago and that continues in my work.

What inspires you to use materials such as crystal, broken glass and volcanic ash to create your sculptures of everyday objects?

The material, in some ways, tells you as much about the idea as what the object looks like. It’s not like a camera that’s painted to look old. It’s actually remade in a material that we associate with geological evolution. I also like this idea that we associate crystals with growth. When it’s introduced into these works, even though they look like they are falling apart and actually degrading, they could also be building and growing back to a kind of completion. So that ambiguity between something falling apart or forming together is a beautiful inherent idea in all my works, really.

You used polished bronze to create the hourglasses on display in the Singapore exhibition. Can you tell us more about this installation?

I work with bronze a lot, but I’ve never done it in a polished way. The works are intentionally unsealed so they will tarnish and there’s this idea that they are ever-changing. The break into the interior of the hourglass contains two objects: one is a clock, obviously a marker of time frozen, and the other is a cast camera. The camera is, I think, an interesting object, as it freezes time. In some ways, both are also recording time. These were a continuation of an earlier series that was an actual hourglass made of glass with two objects on either end. As you turned the glass, one object was uncovered and the other one began a process of burial – so there was a cyclic process of archaeology. I imaged these as a future 10,000-years-from-now version, somehow transformed into another material.

Years ago, you visited Easter Island as part of a Louis Vuitton project. It was a formative moment, as this inspired your future archaeology sculptures. What have been other pivotal moments that have inspired you since then?

I’ve spent a lot of time in Japan. My wife is Japanese, so I’m partially influenced by her as well. There is a care and consideration of everyday life and object architecture that you feel when you go there. I had been there so many times before realising there is a terminology for that: omotenashi. It’s about the thinking that goes behind the way that you wrap something, the way you walk or bow. It’s done to make everyone’s experience have less friction. Something about that type of gesture and care I just appreciate.

How does that translate into your new work?

I think it’s just a desire to pay attention to those things and allow them to enter – the potential of using experience in an exhibition. Not just thinking about the objects themselves, but also how you enter the space and what the light is like.

Is that why you are doing Japanese sand gardens in your recent shows?

Yes. [I’m also making one in] my house. I purchased this 1969 Norman Jaffe house, which is a historical piece of architecture. We did a full restoration and part of the first gesture I made into the landscape design was this garden, loosely based on the gardens I experienced in Kyoto. It’s the same omotenashi idea, in caring for everyday experiences. Even though you see these gardens in Kyoto and they always look the same, they’re actually remade every day. They rake all the leaves out of them and the pattern is reset. This idea of something that looks permanent but is actually totally ephemeral also translates into a lot of the works I’ve made. I’ve integrated some of that language. Those gardens are always white gravel. A couple of pieces I’ve done have introduced colour into the idea of the gardens in a very subtle way. And the idea of an hourglass, this thing that is used as a marker of time when you reset it – it’s almost like cyclical time.

You were recently given access to moulds at the Louvre, which you are using to cast new sculptures. Can you tell us more about this project?

This is for an exhibition I’m working on – the title of the show is Paris, 3020 and it opens at Emmanuel Perrotin in Paris on January 11. I was visiting Musée Guimet, which is a museum that houses Chinese, Japanese and Cambodian antiquities. It was originally part of the Louvre. I went to their storage facility to look at moulds of their objects and in the facility, there were other moulds of Michelangelo’s Moses, the Venus de Milo and other incredible works. I asked the director of the facility if I could use those. She said absolutely not – that’s French patrimony. After that, I asked Emmanuel if he could help me navigate. Through him and the director, I got access, but there were some caveats – I had to test my materials in their moulds to ensure it wasn’t damage anything.

The first Venus I cast was in blue calcite. It’s strange to see these works in this colour, even though it feels somewhat right. I imagine that the work has been encased in the ground, covered over millennia and reformed. A lot of this idea comes from the figures of Pompeii that were encased in ash. The figures were not made of ash; they were calcified over time.

You often imagine your works as coming from the future. Are you optimistic about the future of our planet? What are your views on sustainability and the environment? And how does that feed into your practice?

I never try to be specific about what my work means or what it’s talking about. However, I’m very aware that the works, depending on the zeitgeist of the moment, can mean certain things. I think 10 years ago [when discussing] the origin of the work, the state of the ecology of the planet and the environment was less of a topic, so the works were more related to a sci-fi post-apocalyptic universe. Now, in almost every interview, there’s a conversation around the environment and what’s happening. It’s a huge concern for me. I have two small children, and obviously I think about lineage and what we are making for them. I make my small gestures. All of my travel and activities in the studio are offset. I also drive a Tesla.

Can you tell us more about the carbon offsets you purchase?

I travel a lot, so even though my work has a small impact in terms of carbon footprint, we purchase carbon offsets for all my travel. I brought in a consultant last year to study the carbon footprint that my studio generates in shipping. They’ve come back to me with a proposal on how to offset it. In early 2020, we’re implementing that. So let’s say I want to ship a work from New York to Tokyo – they calculate the carbon footprint of that and I pay to a programme that might be preserving the rainforest or something to regenerate, which counteracts our activities. It’s shockingly inexpensive. So if we have X amount of tonnes, I buy carbon offsets for double that amount. It’s just in this past year that I’ve started to do it. It’s not something I’ve really talked about yet.

Going back to your practice, you said you try to reach wider audiences outside the art world and place art in a context that’s unexpected. How does social media play a role in your work? Do you enjoy interacting with your audience?

Sometimes if I’m on a flight, if I have WiFi, I’ll reply to comments on Instagram. There are certain artists who are happy to make art in a vacuum and it’s really for them. And there are works of mine that are not always shown, but I think my work is completed by people experiencing it… right? In that way, it feels less like a selfish gesture. In the same way that I appreciate art in my own life that’s made by other artists, I want other people to be able to experience that [with my work]. But it’s not for everyone. It’s just for those who choose to engage in it.

You often work with celebrities such as Usher and Pharrell, and in many senses you’ve become one yourself, with some 600,000 followers on Instagram. Would you say you’ve deliberately cultivated a particular style and this large following?

I certainly recognise the ability for my work to reach large audiences has to do with my character and what people are interested in. Warhol certainly knew this, too. [People are interested] not only in the things that I make, but the things that I look at. That could be other artists or the fact that I really like Porsche. I did this collaboration with Porsche and it wasn’t about selling anything. We didn’t sell anything – it was really about my extreme desire [to do it]. You know, when I was a kid, I loved sneakers, cars and cameras…

And you still do.

And I still kind of do! That’s kind of the idea of integrating what’s important to me in my everyday life, even the house that I just worked on. This architect Norman Jaffe, I’ve spent a lot of time to push his character and his work, because I think it’s important. I think he’s one of the most under-recognised architects, partially because he died very young. People want to know that, so I’m sharing it.

What legacy do you hope to leave behind?

I don’t know if I’ve gotten to the point that I can think about legacy in my work. If I can talk about dream projects, this Louvre project is something shocking for me. Personally, it’s an incredible opportunity to have access to all these things. I’ve also started collecting work myself. I always collected art, but it was often trading with living artists. But now I’ve started to collect 19th-century Japanese sculpture. At the end of the Meiji period, there was a tradition of bronze sculpture figures. I’ve had a long-standing interest in small-scale depictions of the figure across time from antiquities to the future. I’ve collected second-century BC terracotta figures that are Greek and Roman. I just bought a 19th-century Gauguin bronze that’s incredible. It was unbelievably inexpensive. There’s a whole universe of sculpture that is shockingly inexpensive – like under $10,000.

When I first interviewed you in 2015, you said you were never quite “accepted or defined” as an artist in the art world. What has changed since then?

That’s an interesting comment. What’s happened is that I’ve stayed the same, but the art world has changed. The art world has realised things that it knew in the ’60s when Warhol was around – that everything about our everyday life can be part of art. This is an interesting aspect that I think has helped my work get into some of these larger museums and institutional exhibitions. I had a large exhibition at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, which was a big moment, and recently I had a show at the How Art Museum in Shanghai. I’ve had a lot of stuff in Asia.

What is your next major project in the region?

I’m working on a show at the UCCA Centre for Contemporary Art outside Beijing [in 2020]. It’s a continuation of the works I’m making for the Louvre project. A lot of the sculptures will be redone in bronze. I’ve done 3D scanning of objects after I’ve remade them and I’m able to enlarge them, so I’m shifting the scale of some of them. They will also have crystals [emerging from them]. They are patinated, so they look aged in an almost art-historical way.