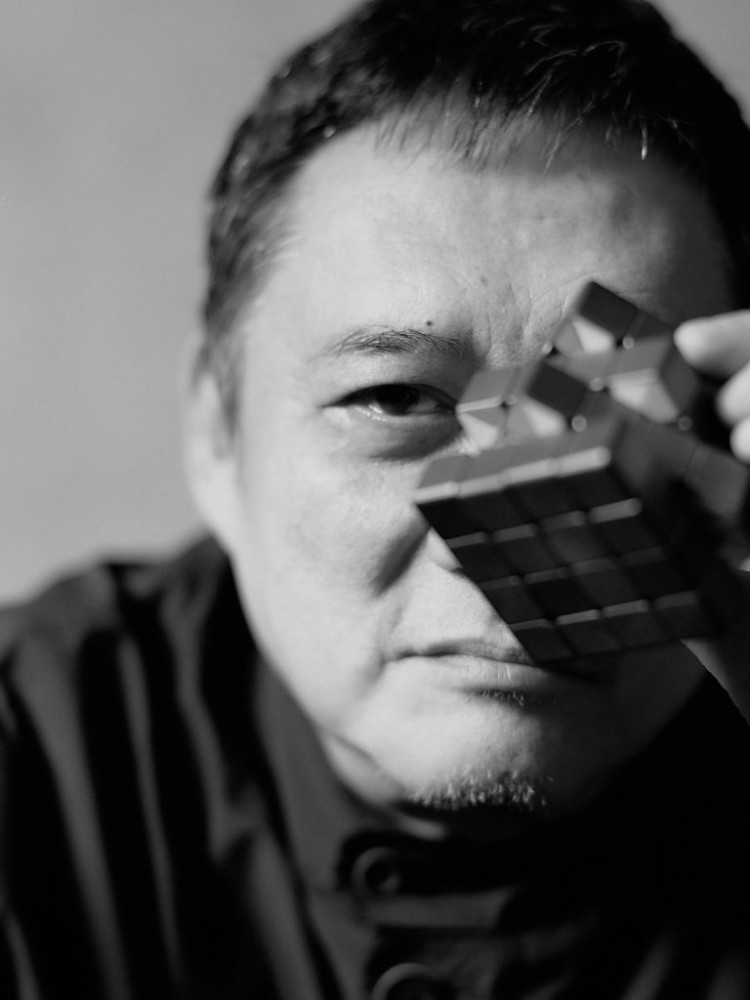

Inside Cover: William Chang on artisanship

Dec 01, 2022

William Chang has built a wildly successful career based on his passion for all things cinema. The production designer of K11’s The Love of Couture: Artisanship in Fashion Beyond Time talks to Zaneta Cheng about inspiration, authenticity and why his work will never be truly done

Look up “William Chang production designer” online and nearly every article or bio mentions his reputation for being shy – albeit often in the context of “quiet genius” – even before his much-lauded collaborations with director Wong Kar-wai on such films as Chungking Express, Happy Together and In the Mood for Love. But there’s nothing shy about Chang’s obvious passion for his work, not only as a production designer but also as an art director, costume designer, film editor and interior designer. It’s simply that he allows the work to speak for itself rather than turning the spotlight on himself.

With his latest project, Chang is doing the same thing he has done for decades – helping to tell a story by turning an idea into a tangible, three-dimensional world. “I know Adrian Cheng and one day he asked me if I wanted to be a curator for the V&A and I thought, ‘Why not?’ I’ve never tried doing this before and I thought it’ll be fun,” he says of his role as production designer for The Love of Couture: Artisanship in Fashion Beyond Time.

The exhibition at K11 Musea’s Art & Cultural Centre, which opens to the public on December 8, is described as “a cultural exchange to explore the evolution of fashion across time and space, a celebration of artisanship and the next generation of designers and a mission to rejuvenate the cultural landscape of Hong Kong”. It features six emerging fashion designers from Japan, South Korea, China and Hong Kong whose task was to take inspiration from the V&A’s historical collection of British and French womenswear and craft new bespoke couture that exudes an East Asian touch. Also included are 12 historical artefacts, all on display for the first time in Hong Kong, that trace the gradual transformation of artisanship in fashion and textiles from the 1830s to the 1960s.

Chang’s first step was to come up with an overarching concept for the exhibition, much like a script provides a context from which to design a film production. “When I start a project, I don’t know how to begin. It’ll stay in my mind but I don’t think about it. It’ll just come out by itself. It took a long time before an idea came up. Then I saw the poem Love After Love [by Saint Lucian poet and playwright Derek Walcott], and I thought about passion,” Chang tells me when we meet at Soho House, whose 25th-floor corridor in which we’re standing was actually inspired by the iconic set he created for In the Mood for Love.

“If you’re passionate about something, you’re always going to continue this passion. The V&A inspired these designers to design these garments, and I thought because they have passion for beauty or fashion or whatever it may be, the young generation, the next generation, generation after generation can continue. This poem talks about how love keeps going and I expanded on this so in the music there’s love after love, lies after lies – there’s a lot of these types of dialogue.”

This idea of enduring devotion, which Chang expresses visually in the exhibition through a brain scan highlighting in colour the synapses that light up intensely when we are in love, is one that he has embodied even before he understood what it meant. “I didn’t realise at first but I would draw on my textbooks,” he recalls of his childhood. “Then when I got older I took some art and design courses like at Hong Kong University. I was interested in everything about art and design. I wanted to try everything. There was no why. I just liked it.”

Chang was 16 when the trajectory of his life was set. “The Graduate made me fall in love with film. The colour, the lighting, the photography, the editing, everything – the way the director, Mike Nichols, used cinematic techniques to convey the story was so special. Watching this movie made me feel like I was in love. I was missing it every day – it was very uncomfortable,” he says with a laugh. “I had to watch it again in order to release the emotions I felt regarding the movie. I started watching more and more films. Back then we had cinema clubs in Hong Kong and I would go watch five, six films every week. It changed how I saw cinema.

“There were a lot of international directors in the ’60s. It was like a revolution of cinema. They destroyed everything and built it up again. And I thought, ‘Wow, there’s so many different techniques, different ways of looking at cinema. There’s unlimited possibilities.” Chang devoured films not only from Hollywood but also from Hong Kong, France, Italy, England, Poland, India and Japan, and discovered a new world of possibilities for himself as well.

“I actually began with fabric design. My boss was great with colours and I was influenced a lot by him. Not because he taught me like one, two, three, four. But because of what he did, what he told me to do, how he criticised my work. And from that I began to understand different things,” he says. “Then after I began film as an assistant director, I thought maybe I should go study film. But he said there’s not much to study – just get into the environment. And it’s true. So much has changed. We used to edit using Steenbeck and now everything is computerised. You just have to learn as you go.”

Also see: 2022 MAMA Awards: What to expect

Chang did end up studying film in Vancouver, but his real training has come through experience, hard work and trusting his instincts. His association with Wong Kar-wai started in the 1980s, when the scriptwriter-turned-director asked him to do the art direction for his first film, As Tears Go By. “It worked well for us. Then we did it again,” Chang told The New York Times in an interview back in 2014, when he revealed his original dream during film school was to become a director himself. “I thought, Why not? Why should I suffer to become a director?”

Chang certainly seems to have found his calling in art direction and costume design, garnering more than 20 honours at the Hong Kong Film Awards and Taiwan’s Golden Horse Awards. His eye for detail – down to the shape of a shoe or style of chopstick common to a particular film’s era – is widely credited for lending Wong’s and other directors’ pieces their authenticity. Often he will spend years developing an aesthetic, poring through photographs and museum archives in order to recreate the look and feel of a particular time period.

“I try to be as authentic as possible,” Chang says, referring to his designs for Zhou Xun’s character in the 2018 Chinese TV series Ruyi’s Royal Love in the Palace. “I want to get as close to the feeling it used to be. Like the costume details, the form. I did a lot of research [on the Qing Dynasty] like how high the slit goes, how tight-fitting, how loose-fitting, the embroidery and so on. It took me eight months. I chose the design and gave it to someone to do and then I followed that person every day. I learned so much, like which colours go together or the different embroidery techniques.”

Similarly, for Wong’s 2013 martial arts masterpiece The Grandmaster, Chang studied the seemingly infinite shades of black worn in mid-1900s China. “I looked at a lot of photographs and I noticed that everyone mainly wore black. And even though the photos were black and white, I saw that they would wear black clothes that were all different materials and textures – thicker ones, silk, thinner ones,” he says of the work that would go on to earn him an Academy Award nomination for Best Costume Design.

At 69, Chang still feels he has much to learn and experience. Whether curating an exhibition like The Love of Couture: Artisanship in Fashion Beyond Time, designing interiors for a private residence or creating elaborate sets for big-budget film productions, his motivation hasn’t changed from when he first started out.

“We used to have a lot of criticism watching movies in the past, like ‘Why would they do that?’ or ‘This would have been better.’ So when I had the choice to do it myself, I wanted to show people what I know. I wanted to express myself and let people see what I can do,” he says. “I’m still developing and that’s one of my prime priorities in the art direction films. I’m always developing because there’s always things I haven’t done before – different stories, different eras. Taste-wise, it keeps developing because of what you’ve experienced. I don’t know if it’s good, but I’m still continuing to develop and reflect, ‘Is this good?’”

CREDITS

Location / Soho House Hong Kong

Photographer / Issac Lam

Also see: Count down to Christmas with these 7 luxurious advent calendars