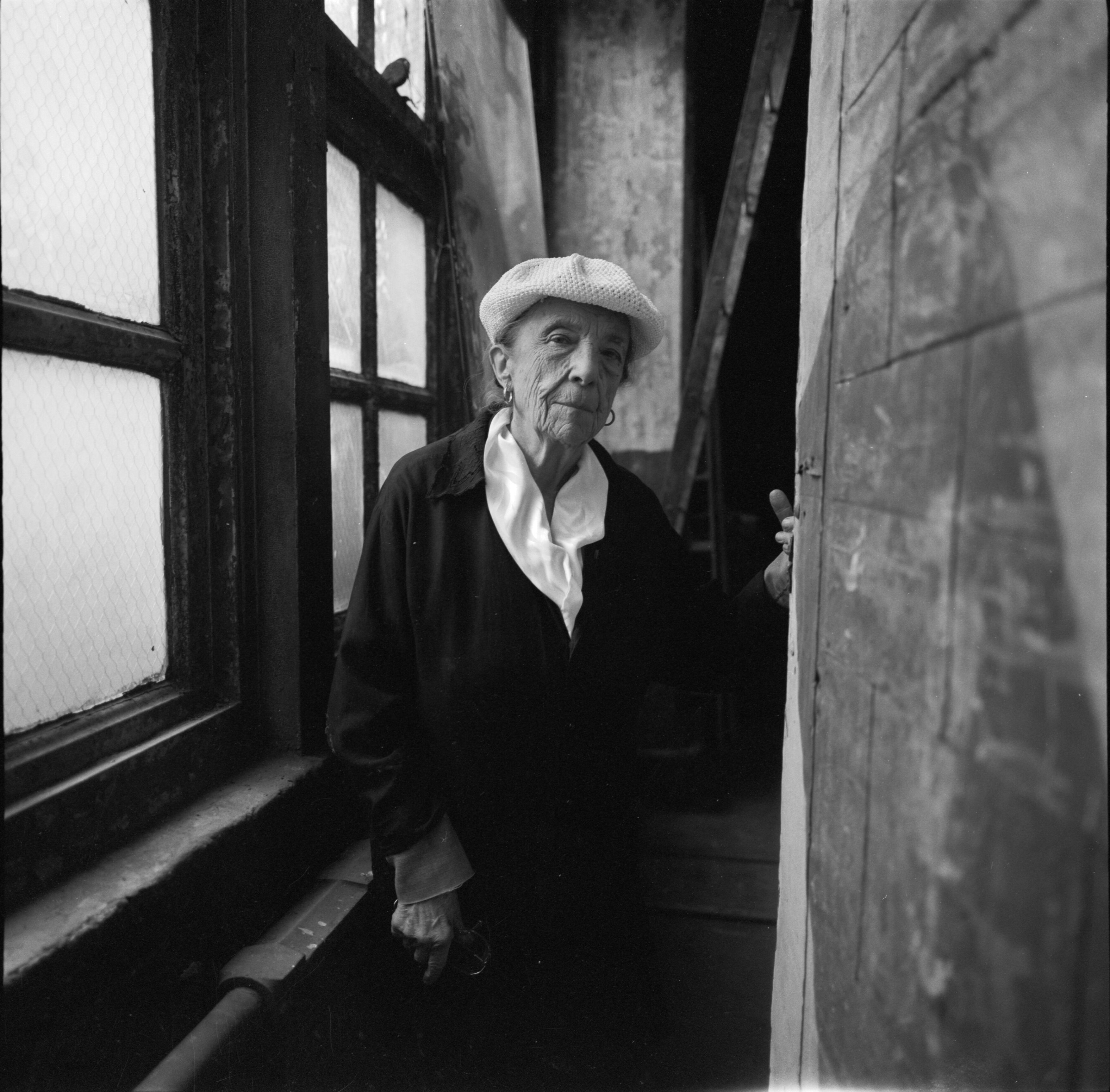

While the spotlight this month may be on the big art fairs in town, Hong Kong’s top galleries are launching their own must-see shows. Jaz Kong reports on the solo exhibition of Louise Bourgeois at Hauser & Wirth

Louise Bourgeois at Hauser & Wirth, March 25–June 21

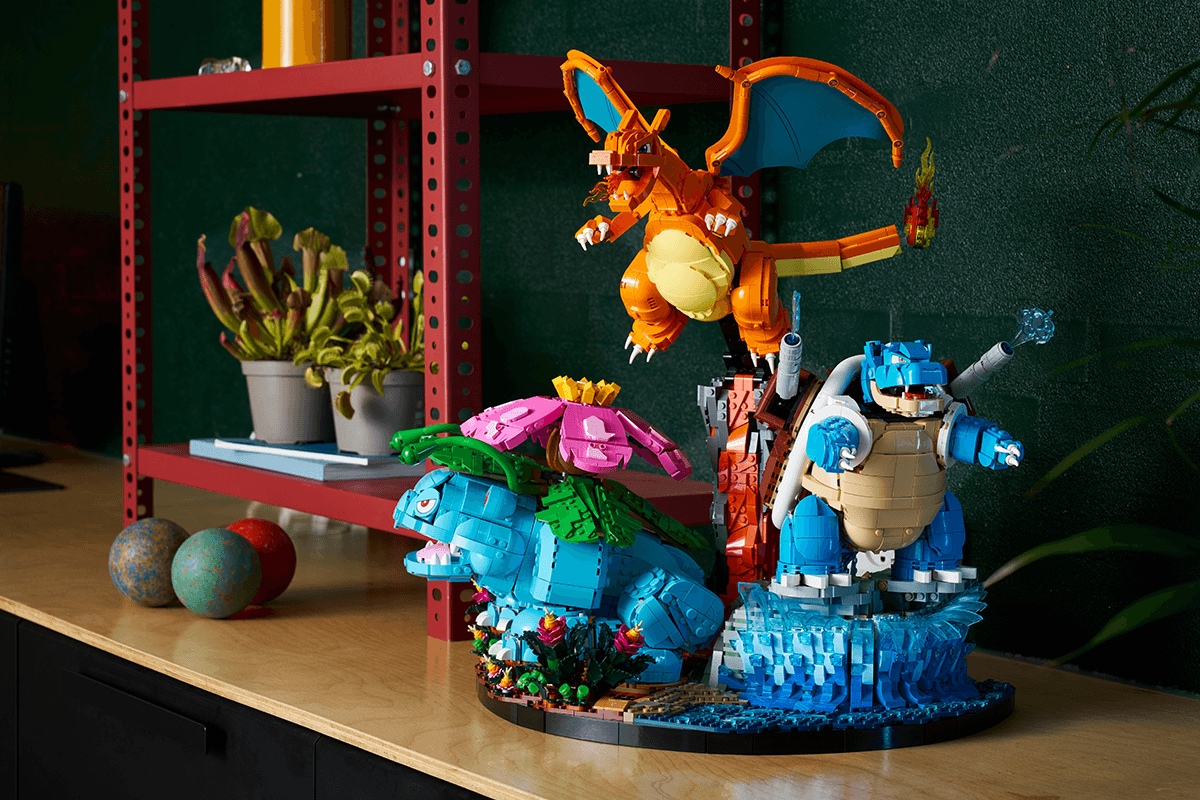

Should an artist create with their own stories? Or should they create a world in response to the society they’re living in, a world that the audience can relate to? The legendary Louise Bourgeois did both and did so brilliantly. Opening March 25 at Hauser & Wirth Hong Kong, and organised with The Easton Foundation, Soft Landscape brings together a selection of Bourgeois’ works from the 1960s to 2008 (when she was in her late 90s), including rarely exhibited sculptures and works on paper. A three-metre-long installation, Mamelles ( fountain), 1991, and a steel and marble sculpture, Spider, 2000, will be shown in Asia for the first time.

How much do we know about Louise Bourgeois, except for her spider sculptures and that she is recognised as one of the most influential artists of the past century? Born in Paris in 1911, she moved to New York after marrying art historian Robert Goldwater, and lived and worked in the city from 1938 until her death in 2010.

What’s inspiring about Bourgeois is that she successfully turned her childhood traumas, including neglect, abuse and betrayal, into fuel and artistic expression, while her sculptures often delved into the emotions of loneliness, fear and jealousy. Her large-scale installations and intimate drawings often oscillated between figuration and abstraction, which we will be fortunate enough to witness in this Hong Kong show. For over seven decades, Bourgeois’ creative process was a form of exorcism: a way of reconstructing memories and emotions in order to free herself from their grasp.

To understand why Bourgeois is Bourgeois, and made what she made, one must not overlook her upbringing. She was indeed born into a Bourgeois family – her parents owned an antique tapestry restoration workshop and a gallery that sold them in Paris. Even though they weren’t wealthy, the family was definitely comfortable. Imagine a French family that’s visionary enough to hire a governess for their kids and teach them English (which in turn helped Bourgeois get through her art degree by serving as a translator for her American schoolmates). However, that was also the beginning of Bourgeois’ nightmare, as she was devastated by the affair between her father and her governess.

The previous show by Hauser & Wirth Hong Kong and The Easton Foundation, My Own Voice Wakes Me Up in 2019, centred on the artist’s family, one of her key motifs. “The palette of the show was dominated by the colour red, the artist’s favourite since it symbolised blood, passion and emotional intensity,” recalls Philip Larratt-Smith, curator of The Easton Foundation.

“For this second show in Hong Kong, I felt it was important to showcase Bourgeois’ range by highlighting another register altogether, and to take the opportunity

to premiere several works which have never been exhibited before, which will be contextualised by being placed in dialogue with better-known pieces. Soft Landscape has a calmer, more contemplative character. In general, the palette is cooler and more restrained. The dynamic tension between figuration and abstraction, another hallmark of Bourgeois’ art, is brought to the fore. The central thematic focus is the relationship between landscape and the human body, which the artist mined in her work, and which is evident here in an iconography of recessess, cavities, holes and biomorphic forms.”

Naturally, the sculptural works by Bourgeois will be in the spotlight in Soft Landscape. It is widely known that Bourgeois created the spider sculptures as an ode to her mother, so much so that when she created one of the commissioned works, she named the 30-foot- tall, bronze, stainless steel and marble spider sculpture Maman, meaning “mum” or “mummy” in French.

As Bourgeois told The Guardian, “She was my best friend. Like a spider, my mother was a weaver… spiders are helpful and protective, just like my mother.” In Bourgeois’ eyes, her mother Joséphine was a patient, hard-working and smart woman whom she loved dearly, which also explains the betrayal she felt when she learned of her father’s affair. Father and daughter did not mend their relationship until much later, after Bourgeois moved to the US.

“The intense physicality of her work, its visceral character, was present from the beginning,” explains Larratt-Smith. “Her famous spiders were conceived

as an ode to her mother, who supervised the tapestry restoration workshop of the Bourgeois family business. Yet the spider is also a self-portrait, for just as the spider spins its web out of its own body, Bourgeois felt she made her art directly out of her body.”

Apart from the Spider series, Bourgeois was famous for depicting body parts, especially female body parts such as breasts, in her sculptures. It’s interesting to see how she played with materials in different variations of them. “The sculpture Mamelles (meaning ‘breasts’ in French), a long, wall-mounted relief of multiple breast forms, was also realised in pink rubber and marble, but the version exhibited here is a bronze fountain with five nipples emitting water,” says Larratt- Smith. “Bourgeois chose her materials because of what they permitted her to express and how it made her feel to use them. She wasn’t interested in marble or wood or textiles per se, nor in their historical or sociopolitical connotations. Bourgeois would realise the same form in different materials to capture a slightly different emotional register or to activate a different narrative around the same subject.”

Other smaller sculptures made in the 1960s will also be on display in the show, serving as testament to Bourgeois’ rebellious nature. Take the bronze-made Lair series as an example. “Bourgeois’ choice of material often went against the grain of her time. The late 1960s witnessed the high tide of Minimalist sculpture, which abolished the hand and favoured geometric regularity in fabricated (sometimes prefabricated or industrial) objects,” Larratt-Smith says. “It was during this same period that Bourgeois decided to work in marble and bronze – perhaps the most classical materials of all.”

While Bourgeois’ 3D works are seemingly more well known, her paintings shouldn’t go unnoticed. Bourgeois began her creative journey with paintings and prints (and before that, mathematics, which is rather surprising), and her print shop was actually where she and her husband met. She then started to explore the artistic expression of sculptures, and later went through a stage of heavy psychoanalysis before shifting back to paintings in her later years. While Larratt-Smith believes there is no hierarchy between Bourgeois’ 2D and 3D works, he says, “I think the practice of drawing offered Bourgeois the most spontaneous expression – the most immediate psychological release, to use her words – whereas the act of making a sculpture tended to be more involved. Working against the resistance of the material gave her an outlet for her aggression. As Freud said of the analytic method, it was a process of making the unconscious conscious.”

Looking back at history, Bourgeois was around during a turbulent time. She lived through both World Wars, and like a lot of female artists of her generation, she was first underrated and overshadowed by a lot of male painters, as well as being eclipsed by the popularity of abstract expressionism during her early to mid career. It wasn’t until she was 70 years old that MoMA did a retrospective on Bourgeois, and recognised her as one of the most influential artists of her time.

“Bourgeois didn’t express her views on sociopolitical issues through her work, but in the late 1960s and ’70s she actively participated in roundtables, marches and other events that raised consciousness about gender inequality in the art world,” says Larratt-Smith. “There’s no question she was a feminist in her life, but she strongly disliked being called a feminist artist because she felt that term excluded too much and that her work dealt

with pre-gender issues anyway. In other words, her relationship to feminism was highly ambivalent. She once said that her art aspired to take women from an object

to a subject. Yet she also believed in the fundamental differences between men and women.”

Another surprising fact is that what Bourgeois went through is actually highly relatable to our time. Larratt-Smith states that “the notion of identity is a hot topic these days. For Bourgeois, identity is formed and defined through the relationship to the Other. At the same time, Bourgeois was a master storyteller, and the works she created are also symbolic narratives about her life that were and are powerfully compelling. This combination of mythmaking and transparency, confession and symbolisation makes her work all the more relevant in our age of social media and exhibitionism.”

Larratt-Smith also describes Bourgeois as a “confessional artist”, and one thing we could learn from her is that “Bourgeois believed deeply that if she told the truth about herself then she could make herself understood and be forgiven. She also believed that everyone should be psychoanalysed in order to understand and accept themselves.”

In this day and age where we rely heavily on the façade of social media, how, one might wonder, to confront ourselves with the truth of who we are?

Also see: Art Central reveals programme highlights for 2025 edition