“I do not like green eggs and ham,” says Sam-I-am in the famous Dr Seuss title of the same name. To which Daniel responds: “Try them! Try them! And you may. Try them and you may I say”. Of course, Sam-I-am approves and praises the dish, going so far as to say he would eat them in a boat or with a goat.

One wonders how Sam, or anyone else for that matter, might respond to something a little more radical. Locust? Perhaps not, or at least, not yet.

Few of us could honestly say we rub our bellies with gastronomic glee at the prospect of consuming insects. We may know our nouvelle from our molecular, but not our entomophagy, the term for eating insects. Sustenance is both a subjective and wide-ranging topic. Plants don’t always taste good – you could eat dandelion greens until the cows came home – but they are not entirely unpalatable and contain many nutrients. By which measure insects are perceived as being edible but not to be enjoyed.

But that’s blinkered thinking. Many of us will never know how tasty certain insects can be, celebrated as they are in other cultures and geographical contexts; larvae in acacia roots in the Australian outback, for example.

Indeed, not only has mankind been indulging entomophagical treats since prehistoric times, but the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation estimates that more than 1,000 species of insects are consumed in 80 per cent of the world’s nations. Once discovered, the world of insects bears a striking portfolio of treasures, from rhinoceros beetles, scorpions and tarantulas to cicadas, grasshoppers, bamboo worms and crickets.

Crickets are the chicken of the insect kingdom and many smaller companies in the United States, such as Tiny Farms and Aspire, are producing cricket flour for use in snack bars and for baking cakes, and now pasta makers are getting in on the act.

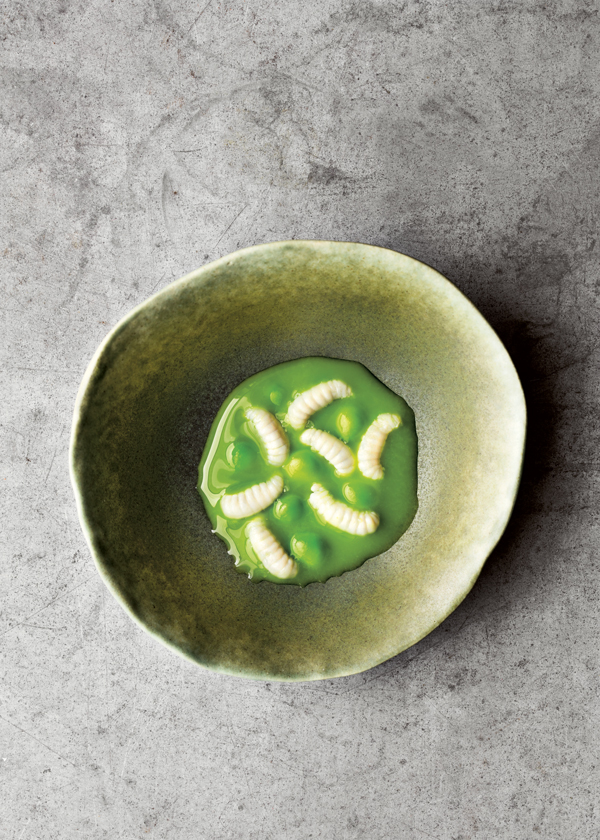

This basic premise inspired the team at award-winning René Redzepi’s Noma restaurant and its dedicated Nordic Food Lab to investigate the palatable potential of the insect world. The result is On Eating Insects: Essays, Stories and Recipes, released on May 1 and published by Phaidon. The book’s authors are lab specialists Josh Evans, Roberto Flore and Michael Bom Frost.

It’s engaging fare too. The writers are less interested in insects being the salvation of humanity than they are in acknowledging culture and the work of our shared ancestors, which gives the book a highly enlightening and intimate tone. Note Flore’s words on the recipe for Smoked Lactuca, a type of wild lettuce. “I am proud of my Sardinian heritage. I know a lot about the dietary habits of the ancient Nuragic people of Sardinia,” he writes. “It is known for certain that hunting bees for honey during this era was a dangerous practice reserved only for men. The Nuragic people also collected wild herbs and evolved sophisticated gastronomic techniques such as smoking, baking and boiling. In areas of Sardinia, like Barbagia, and Gallura, the dish Latuca e Mele (Lettuce and Honey) is still part of the common heritage, even after 3,000 or so years.

“Ants, attracted by honey, faced their doom as they became trapped inside this sweet, sticky glue, so I can imagine how the people of this civilisation became used to consuming the honey, wax, bee larvae and ants in one mouthful. This dish is dedicated to Giovanni Fancello, for his tireless effort to shed light on the ancient history of food, especially that of Sardinia.”

It’s not just food the book features but libations too. Here’s Josh Evans on Anty Gin and Tonic. “This cocktail was developed by Ben and the team, as part of a menu for an event we did called Pestival at the Wellcome Collection in London in the spring of 2013. We designed our own Anty Gin in collaboration with The Cambridge Distillery, which in addition to the requisite juniper and a few supporting botanicals of wood avens (Geum urbanum), alexander seed (Smyrnium olusatrum) and stinging nettle (Urtica dioica), features red wood ants (Formica rufa) as the aromatic star. The result is a complex, well-balanced gin; the ants bring key citrus notes and, for me, a distinct tingling on the tongue, similar to the feeling a few minutes after eating a nasturtium seed.

“We coloured our G and T with a drop of carmine, which is derived from the scale insect cochineal, to begin the event festively and illustrate, with the first taste, already two different ways of using insects for their sensory properties that do not involve consuming one whole. Half-fill a tumbler or highball glass with ice cubes, then add the gin, carmine and tonic water. Stir lightly, decorate with dried whole cochineal, if using, and serve.”

That is something I would drink in a boat or with a goat.