You’ll never sell it online – not in a month of Sundays, they said. As the worlds of music, literature, film, furniture, property, fashion and fast-moving consumer goods of all declensions succumbed to the digital arena, there was one category that would never succumb to the elect ecosystem, they said: art. It’s too recondite as a sector to be commercially pragmatic and too stealthy to become stentorian in its electronic sales splendour.

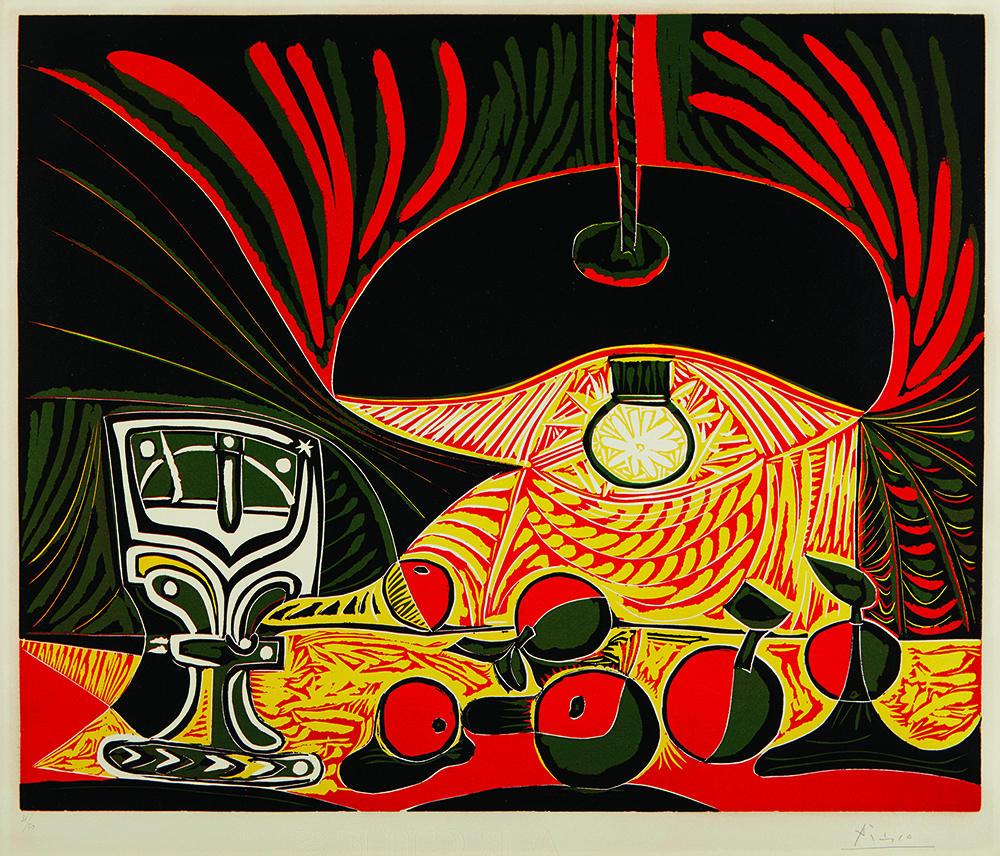

Art doesn’t traditionally operate like other product categories. Consider a very recent (and ongoing) situation. Picassomania is currently sweeping the global art world, with the artist’s sales potentially poised to break the US$1 billion barrier this fiscal year alone. Specialists, dealers, curators and academics generally determine the provenance and the price of such masterpieces for us. But then, Picasso’s Fillette à la Corbeille Fleurie (1905), a painting from his Rose Period and the crown jewel of the late David Rockefeller’s collection, has just been toured around the world by auction house Christie’s, which is representing Rockefeller’s estate.

Christie’s had originally set the work’s estimate at US$70 million, only to revise that by almost 80 per cent up to US$120 million, given how great and deep demand for the work appeared. The moral of the story being: if putative art industry cognoscenti can still be surprised to the tune of 80 per cent, what hope do the rest of us have?

“I think the art world – this is before Artsy – is too complex an industry for someone to try and replace it,” says Sebastian Cwilich, the New York-based CEO of aforementioned art platform Artsy, which counts Dasha Zhukova (the ex-wife of Russian billionaire Roman Abramovich), Wendi Deng (the ex-wife of media magnate Rupert Murdoch), Marc Glimcher (the CEO of Pace Gallery), Larry Gagosian and others among its illustrious board members.

But that’s precisely why Artsy has been trying to build bridges and inroads into the art world over the last nine years–to try to make a previously inaccessible market accessible. More specifically, 10 days before Cwilich and I meet, his company launched on the WeChat platform in China. “What we did was figure out a partnership model, which kind of allows us, whether it’s curating, or representing artists, to help them reach a larger audience,” he explains.

Not only has art defied the naysayers who said digital sales would never happen, but it’s also over-reached its potential in a very short space of time. An April report by insurance provider Hiscox shows that online sales of art and collectibles rose by 12 per cent to US$4.22 billion in 2017. (Five years ago, that figure was US$1.5 billion – and the report estimates that online sales will continue skyrocketing over the next five years to US$8.37 billion by 2023.) A separate report released in March by UBS and Art Basel suggested that as much as US$5.4 billion in art and antiques had been sold online in 2017, marking a 10 per cent rise over the previous year. All of this means that online art transactions aren’t just strengthening, they’ve graduated from being an emerging market to a more established one.

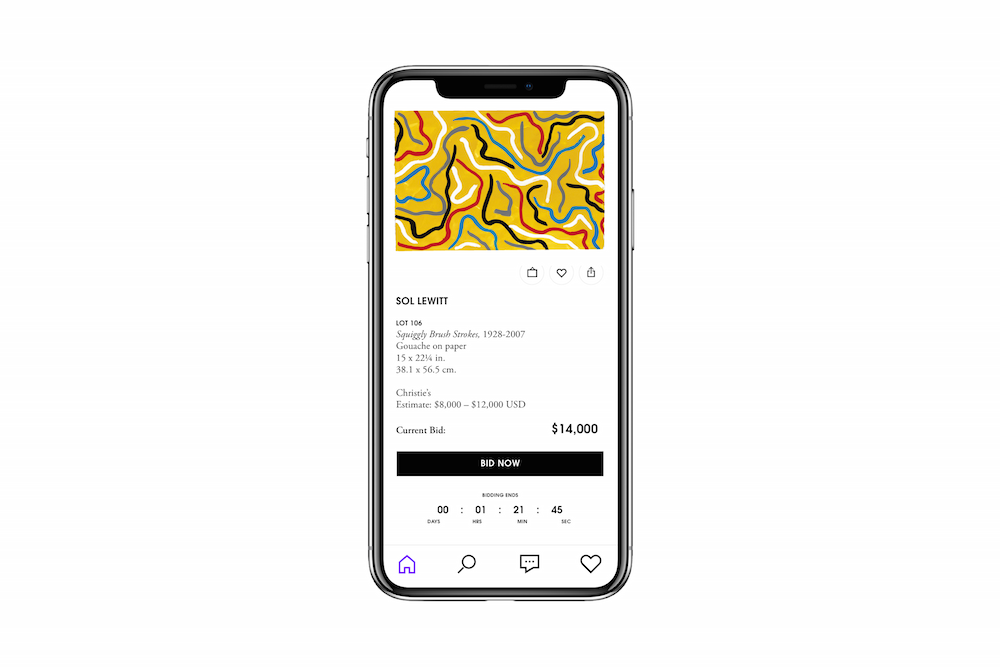

Artsy represents a critical mass of galleries (around 2,500), auction houses and art fairs on its platform; galleries pay the company a small monthly fee to be represented. But Artsy doesn’t directly sell to prospective clients as much as it simply points them in the direction of such galleries who will – and it does that by utilising technology to create a better buying experience. “Right now, it’s easier to buy a book on Amazon than a US$1,000 picture,” says Cwilich. “So we need to create the right experience, the right shipping, the right insurance, the right information around the work – to create that experience that people now typically expect across every other industry.” He cites that as Artsy’s biggest challenge going forward.

This writer first signed up to Artsy’s newsletter in 2008, having read that Dasha Zhukova had commissioned Rem Koolhaas to build the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow. As a subscriber, I get pointers to works by Chinese photographer Yang Fudong – I’d once written to Artsy to ask why Yang was so undervalued as an artist, only to have ShanghArt (which represents him) write back to say what “good value” his work therefore represented. Regular emails flag works by American artist Alex Katz or German photographer Gerhard Richter as they come to market, and so on. On the morning I wrote this piece, an email arrived announcing three new works I should know about by Zhang Xiaogang, Edward Steichen and Zeng Fanzhi, as well as works by Ai Weiwei starting at US$500 and one by Maria Nepomuceno at US$20,000.

It’s all part of the broad and enlightening Artsy experience that Cwilich is trying to cultivate. “We are actually curatorially driven,” he explains. “There are art historians who look at works of art and make connections between different artists. So if you’re following certain pop artists, you’ll get suggested works by another. And you have to do that in a curatorial way in the art world.” He elaborates: “Artsy is going to create the type of user experience that makes it the best way to buy art. Whether it’s the discovery phase, the fulfilment phase or the value phase – why this artist above that artist? And how does the end user have a great experience buying art?”

What distinguishes art from books, or Artsy from Amazon, is that the latter behemoth uses something called collaborative filtering. That’s great, explains Cwilich, at telling you, “for example, people who bought this spoon also bought this fork. But it doesn’t know why that’s the case. It just knows that these two details are connected.” Artsy’s system, he says, brings more depth and an educational component, encouraging people to start learning more about art. “It’s more elevated,” he says. “People need to enjoy art.”

Perhaps most remarkable is that the more than US$4 billion in online art sales represents just a tip of the iceberg of the larger collecting landscape. “Today, 98 per cent of millionaires in the world do not collect art,” shares Cwilich – a tantalising insight indeed. “In general, the number of people who could buy art is much, much bigger than the actual amount. Perhaps the majority of your readers could be buying art, but they don’t. They have nice watches and nice cars, but probably the large majority do not have original art on their walls. But they could. So how do you create an experience where people don’t feel intimidated, where they can feel confident and educated?”

Just don’t expect Arsty to establish any kind of Mr Porter Style Council of tastemakers, ambassadors and opinion leaders who serve as arbiters in a parlour game of artful taste. “We do have a collector relations team, so they advise people already,” says Cwilich. “But I wouldn’t say it’s like a style panel and they’re not public. It’s not like we’re saying: ‘Everyone must buy Jeff Koons.’”

Artsy attracts close to 2.5 million visitors each month, according to data analytics, and is the top-ranking art marketplace on Google, attracting viewership from more than 160 countries. Founded by Carter Cleveland in 2009 while he was still a student at Princeton University, legend has it that he was unable to find a site selling art to decorate his room on the internet, so he launched Artsy as an opportunity window for global art sales. The company is now valued at more than US$3 billion.

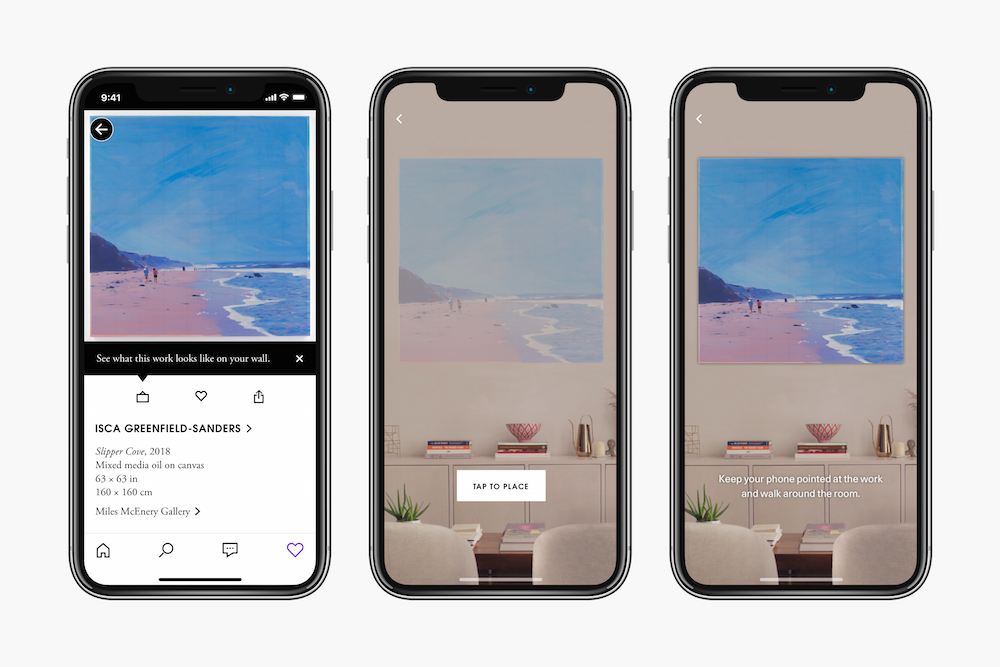

Tech is naturally a driving force for Artsy and the company has close links with Apple – the site’s demo apps have been used as part of the tech giant’s keynote talks, and Artsy has its apps in Apple stores and on its TV commercials. “Now we’re launching a new technology that allows you to do augmented reality in a much better way,” says Cwilich. He grabs his smartphone and demonstrates. “There’s been a lot of people launching features allowing you to see paintings on walls, but this allows you to take any work from Artsy and essentially point it at your wall to see how it looks in three-dimensional perspectives. You can even turn it and see the edge of the painting. That’s super-exciting!” It launches two weeks after we meet. “We’ve been developing it since Christmas,” he beams. “Apple has certain partners, like Artsy, who they encourage to develop apps, so they can say to their consumer, ‘Here is a great new product.’”

Artsy does have competition, from the big auction houses online to the smaller operators (ranging from Tang Contemporary to Paddle8 and the art portal Artnet), but none have fared as well. Why? “A lot of people wanted to be their own auction house and compete with Christie’s, Sotheby’s, Phillips and everyone else,” says Cwilich. “We said we want to be a platform to let those auction houses reach a wider audience. So that’s a fundamental difference. Also, we’re technology people first, and I think that has helped us create the sort of user experience, which our partners and our users really love. And that has let us build the company quite quickly.”

In a world where Da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi just sold for more than US$400 million, what’s a better investment right now – art, tech or both? “I was having a conversation with a hedge-fund manager last week,” says Cwilich. “In this world of very fast-changing technology, if you had to buy a company stock today and hold it for 50 years, I asked him, ‘What would you buy?’ And quickly he said, ‘Well, it might be Amazon, but it might not be Facebook.’ If you want to buy art, there’s a pretty good bet that if you buy a Da Vinci or a Warhol, you’re likely to be okay. From that perspective, buying an established artist is a kind of stored value – and might be a better source of value than companies getting disrupted by technology so frequently.” Happy shopping, artful punters.

This feature originally appeared in the May 2018 print issue of #legend