Industrial Designer Elaine Yan Ling Ng Is an Alchemist of Tomorrow's Lifestyle

Apr 27, 2016

Re-creating nature is Hong Kong industrial designer Elaine Yan Ling Ng’s grand endeavour. Using next-generation materials and technology, she seeks to harness nature’s ways to improve architecture and interior design. It is called biomimicry – the emulation of nature in how materials respond to heat, light, electricity, sound and motion. To Ng, it’s living architecture.

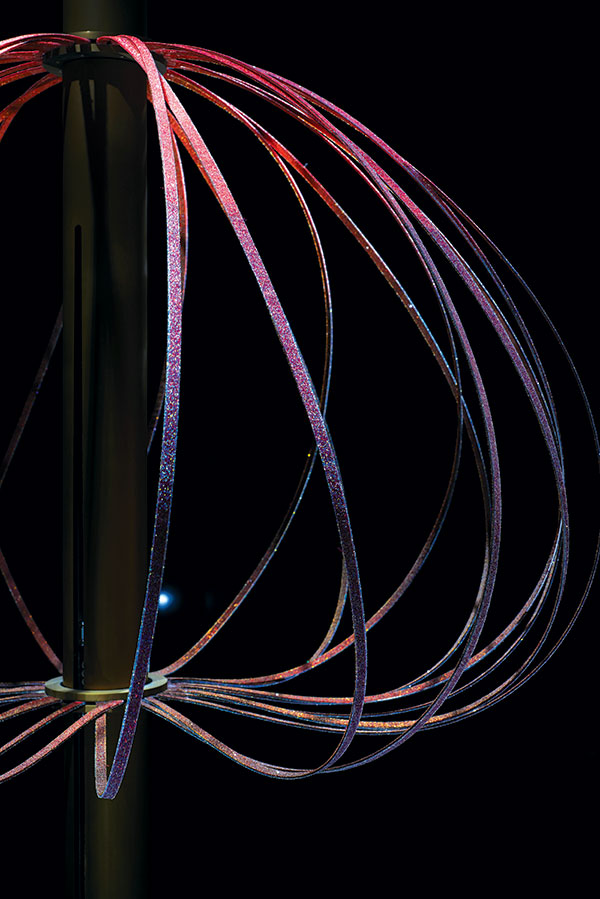

That much was evident at a Hong Kong Art Central event in March, where one of Ng’s pieces, a spectacular kinetic crystal installation called Sundew, stole the show. Ng’s vivid work employs textiles, bamboo, electronics and more than 2 million crystals. It mimics the carnivorous sundew plant, which attracts its insect prey with scent and reflected light, then ensnares it and digests it rather like a Venus flytrap. Visitors to the exhibition were drawn to the beguilingly beautiful, scent-emitting Sundew in much the same way as a sundew plant’s prey is lured to its fate.

It was the fate of Nadja Swarovksi, of the Austrian glassmaker Swarovksi, to be ensnared by a prototype of Ng’s work shown at Salone del Mobile in Milan last year. So hooked was Swarovksi that she dubbed Ng a Swarovski Designer of the Future. The accolade impelled Ng to expand Sundew and have it shown and sponsored by the Swarovski company at Hong Kong Art Central.

“We got freedom to design anything we wanted, with or without crystals, and sent our ideas to Swarovski headquarters,” Ng says. She has a degree in future textile design from Central Saint Martins in London and is co-founder of textile consultancy The Fabrick Lab in Hong Kong. Ideas are her forte. “Nadja is amazing in terms of how fast she makes decisions and how fast she pushes things. So the timeline was crazy. It took a lot of people, a lot of work, and the small matter of about 20 million crystals.”

Sundew is sound-activated. Clap, sing or shout, and the component organisms respond by recoiling, closing or elongating, like iridescent disco divas. “I love looking to plants and their protective mechanisms,” Ng says. “They serve as a function in design and movement for humans, too.” She says English design apostate Thomas Heatherwick liked Sundew. “He mentioned the mechanism, how the engineering work is so complex and yet the movement appears very simple,” she says. “He liked that contrast. And he liked that I’d used bamboo to do it, thereby creating a more lightweight structure in both form and volume.”

Glass crystals were a material unfamiliar to Ng. “At first I thought, well, crystals, they have a connotation of being cheap and also decorative,” she says. “So I saw them as the starting point for something more than just decorative, and set about intuiting how polymers might interact with crystals. That was my focal point: a kinetic structure and how it becomes an architecture and interior.” Now she’s a crystal convert. “After visiting the Swarovski headquarters in Wattens, Austria, I regard crystal as an ingredient for making new material, texture and surfaces, and for this project it’s exciting to be combining craft and technology to explore new functions.”

Living architecture is The Fabrick Lab’s business. “It’s a key research area,” Ng says. “Since graduating I have continued to study polymers, alloids within the living ecosystem of an architectural structure. When you think of building, you think of bricks. But, now, such applications don’t need to be brick anymore. It can be a woven structure, or borrow techniques from different disciplines.”

Ng knows a thing or two about practical design, having worked for Nokia for two years, studying plastics. She and a team of industrial designers looked at the textures, colours, and forms of plastics. “It was very experimental,” she says. “We got great support for projects and did some really cool stuff in terms of research and development.” But broader applications of science and technology than mobile phones lured Ng away.

Ng’s favourite fashion designer is Iris Van Herpen of the Netherlands, whose cutting-edge creativity puts science in the service of her imagination. “I love her water dress, and the crazy tweedy printed dress,” says Ng. In studying for her master’s degree, Ng specialised in programmable textiles. She learned how to create interactive designs with woven textiles in a collection she called Naturology, bringing nature and technology together.

Ng has also created adornments of the human form. She used experimental reactive textiles to make finger and shoulder extensions. She combined layers of fabric and thermochromatic resin with a reflective veneer. “By adapting to fluctuations in light, temperature and humidity, the structures fluctuate and morph into new shapes in a way that celebrates nature’s survival tactics,” she says.

So what comes next, after Sundew? “I wouldn’t rule out cactus plants, for example. Every plant has a survival mechanism and the advanced cactus survives on so little water,” Ng says. Sundew and its movements have aroused her curiosity. “It’s beautiful to study human movement with shapes like these, to see how they react to different base, middle and top notes, each gesture giving different feelings. I think that could be beautiful to explore further.”