“I never assumed I would be successful and success has brought me trouble. Success came early. Now many people expect me to be better and better, so there is pressure. It’s not just pressure from the outside, but from my own inner self as well.”

Never has American icon Marilyn Monroe sounded so Marilyn. Except it’s not the blonde bombshell of Hollywood’s golden era, born 90 years ago this month on June 1, but contemporary artist Chen Ke, 38, lamenting her breakthrough success in 2010, aged 32.

Chen is in Hong Kong prior the opening of her first full-blown show in the city at Galerie Perrotin, an event she will share with Swedish artist Klara Kristalova until June 25.

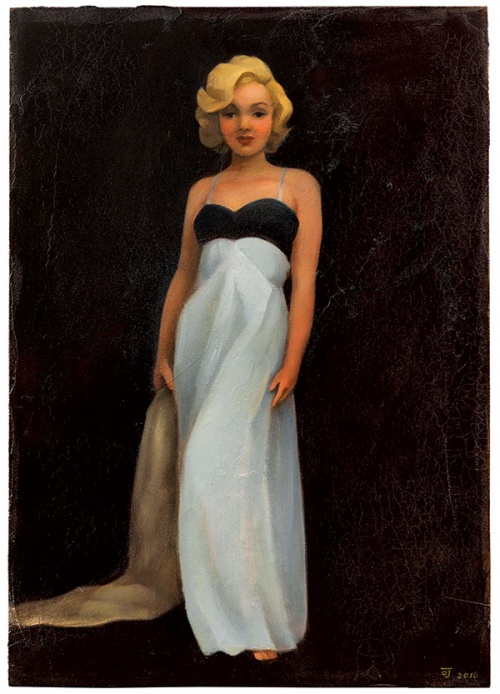

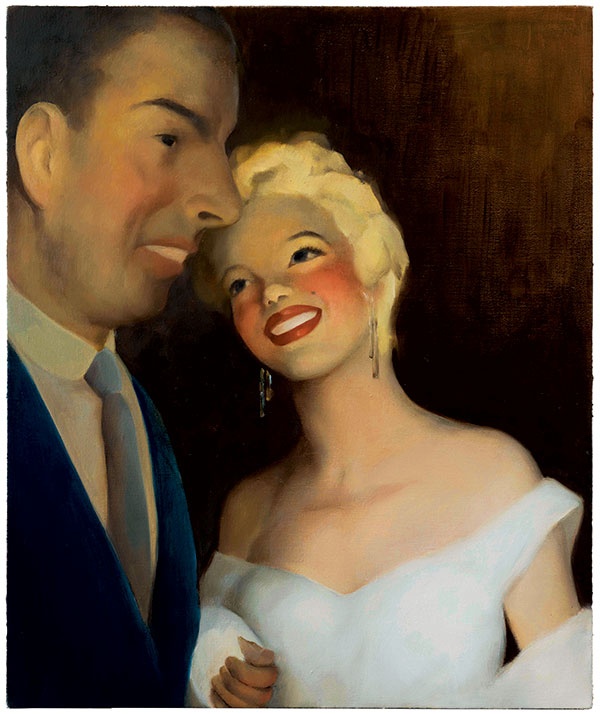

For her latest works Dream Dew, Chen has chosen Marilyn Monroe. Translate the iconic star’s name into Chinese; dream and dew are the qualities derived. Chen’s choice of icon is no small irony. Fame, the mass media, consumer culture and celebrity commodification; such is the Monroe legacy, a cultural type that can be reproduced, transformed and enacted by others to suit their own culture. Part of that commodification is due to Andy Warhol. But Monroe, above all, has become the projection of the American-ness of pop culture. Warhol’s work in particular emphasised the commodification of celebrity – its ability to be bought, sold, transmitted and, most of all, consumed. It’s popular culture as the promise and premise of easy pleasure; a surface-level gratification.

Warhol was once asked why he only painted Marilyn after she died: “The Monroe picture was part of a death series I was doing of people who had died by different ways. There was no profound reason for doing a death series, no ‘victims’ of their time; there was no reason for doing it all, just a surface reason.” It was art as artifice or iconicity – no purity or originality. The icon becomes its own context and, therefore, refers to its own emptiness and banality. Celebrity reinforced as celebrity.

Chen’s work walks head-long into the Marilyn melee, but from pre-celebrity. She seeks out the authentic Marilyn preceding the movie star, depicting the individual and not the icon living as a copy. The depth, not the image, is Chen’s point of entry. Respect, not reproduction, the dream not ditz-glitz.

“I came across some old photos of Marilyn taken when she was very young,” says the artist on the morning of her opening. “This is very different from the impression I had of Marilyn. So I tried to read a lot of books, watched movies to find the real Marilyn and ascertain what she was like outside of what we saw in movies. I was very curious about her background. She must have been a very complicated personality and had been living with anxiety because of her difficult childhood. I tried to dig down into that topic.”

Is Chen an anxious person and did that help her empathise with Monroe? “There is a gap between reality and dream. Our impression is so different from the real person. It’s about tackling the gap. It’s about finding our own dream. We live for nothing in the end, but still we must have some hope. Marilyn’s like a dream to all women. She dreamt hard; it’s about fighting for a dream.”

Chen seems fascinated by the celebrity she seeks to deconstruct. “I want to get more power from other people’s lives. From celebrities, or big names like Marilyn. I see myself in her.” What about the likes of Gong Li and Fan Bingbing on her doorstep in mainland China, surely they are no less iconic in present-day culture than Monroe in olden-golden America. “As a woman, I appreciate their inner strengths instead of sexiness, same as Marilyn, they are very powerful and tough women.”

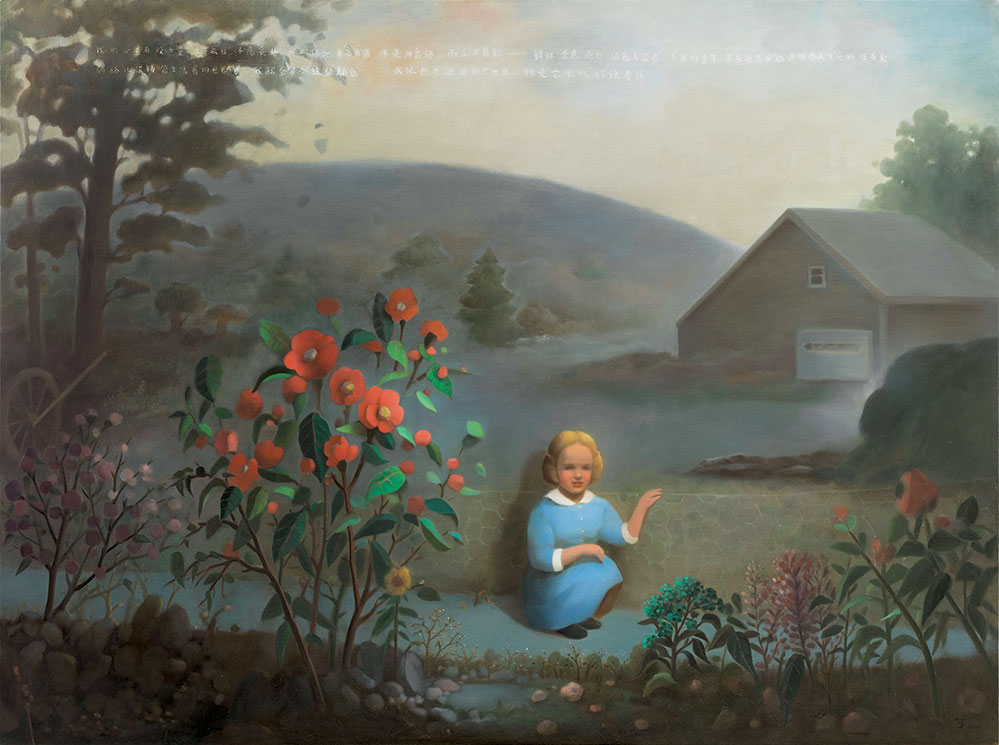

Those unfamiliar with Chen’s work won’t likely guess at her previous incarnations on canvas. She’s typically been associated with loneliness, not uncommon in the One Child System and its urbanised and commercialised society, and invoked those feelings of isolation and estrangement through the presence of a button-nosed little girl, who is depressed, introverted, living a naïve existence in an illusory, other-worldly space.

For Chen, inverting reality gives her a true sense of reality, and viewers see the worried little girl in her paintings and feel a sense of sentimentality, a feeling not unlike seeing the work of Japanese artist Yoshitomo Nara, whom Chen admits being influenced by. Titles such as With You I Will Never Feel Lonely see her paint the little girl on vintage furniture, fabric, but often just in patches of paint.

But just like Marilyn, the little girl grows up. Chen projects herself strongly into her art. She says if even one day passes without painting, she is enveloped by emptiness. A day without canvas, in a Monroe-esque parlance, is like a day without klieg lights or cameras. Chen was born in Tongjiang, Sichuan, and graduated with a master’s from the Sichuan Academy of Fine Arts in 2005. Married and the parent of a 4-year-old daughter, she currently lives and works in Beijing, a city where the art competition doesn’t get any tougher. “I live in Beijing so I’m aware of other artists’ styles, it doesn’t bother me. As an artist, I’m looking for uniqueness and difference. It is so competitive in today’s China, you have to really know what you want and what you’re doing.”

How does she feel about being called a contemporary Chinese artist at a time when many of her peers are resisting the ‘Chinese’ moniker? “I love it. It’s relevant to the world. But the world is multicultural, so it’s not my aim to let people know I’m from China or Chinese. It should be effortless, the cross-cultural exchange. It should just come naturally. So, in the case of Marilyn, the figure is from the Western world and also the skills, much like Western painting technique, but the philosophy in my works is Asian.”

I ask if there’s one work of her own, in her career, that she’d choose to single out or keep. “Did you see the little box,” she says, referring to a beaten-up old wooden case, on which she has painted Monroe inside and a version of herself on the adjoining mirror side.

It’s called I See you, and I See Myself. “This is the only work that shows my relationship with Marilyn,” Chen says. “I see more of myself in that piece. All the others are about Marilyn. It’s a very good conclusion for this exhibition. The box itself has its meaning, it’s made for daily use and very different from working on a canvas.”

“Fame is fickle,” said Monroe later in her short life. “If it goes by, I’ve always known that it was fickle. So, at least it’s something I experienced, but that’s not where I live.” Unlike Chen Ke.