Believing that art is a means of subverting reality, Iván Navarro uses electric lights and mirrors to transform ordinary objects into instruments of power and surveillance. Dionne Bel delves into his world to learn about his creative process and his latest cosmic paintings.

Iván Navarro grew up under a military dictatorship that used electricity as an instrument of torture and frequent power cuts as a way to isolate and terrorise citizens. But the Chilean artist has used that same form of energy to both create a name for himself and critique systems of authority and control, illuminating furniture and architectural fixtures from tables to water towers with his signature fluorescent and neon lights and plunging viewers into abysses of seemingly infinite space.

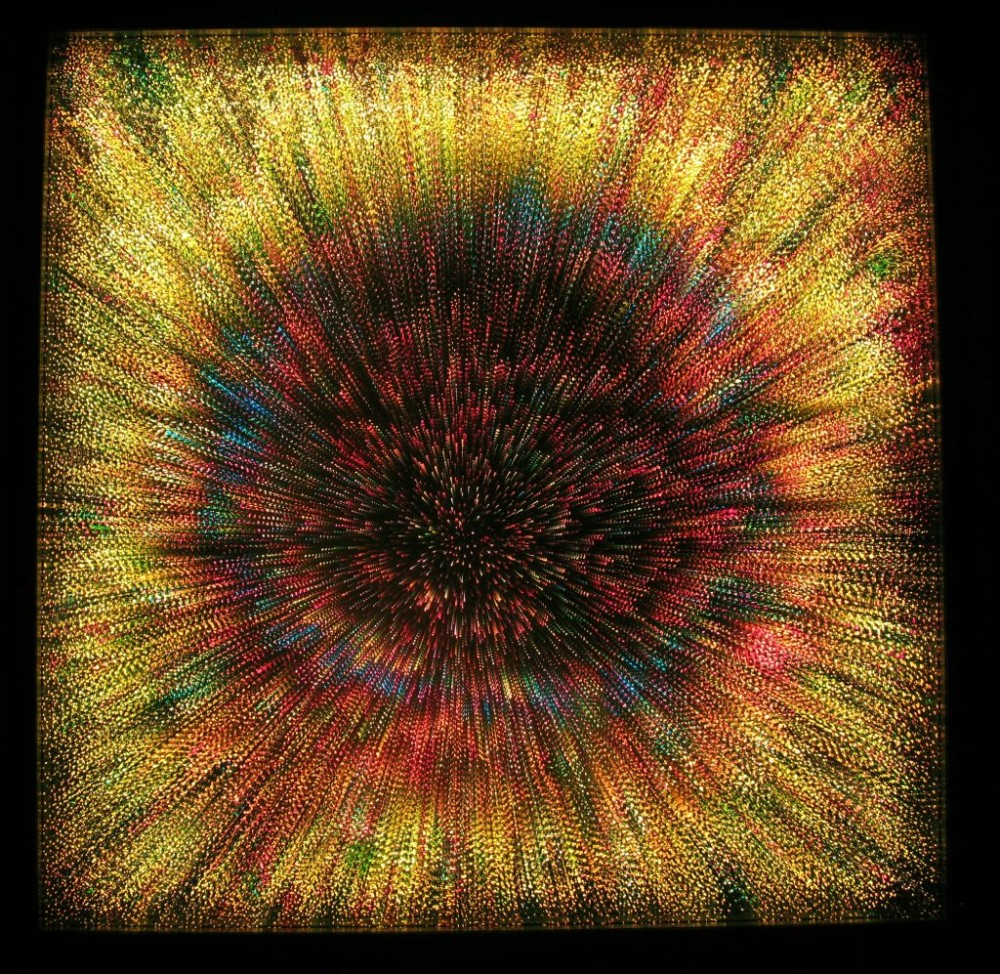

Following a recent retrospective of his 20-year career at Parisian cultural centre CentQuatre, the New York-based artist’s latest exhibition, Planetarium, running until March 27 at Paris’s Galerie Templon, marks the first time Navarro is using paint. The “return to handmade production” was partly a response to COVID-19 and partly an exploration of cosmic landscapes and celestial phenomena. He shares his inspiration, intentions and why it’s important to continually challenge people’s perceptions.

What was it like growing up in Santiago under the Pinochet military dictatorship?

My father was a university dean in charge of the propaganda department connected to the socialist Allende’s government, so once the coup happened, my father was taken to prison. I was only a year old, and then he was freed after six months.

We grew up in fear. What if they take my father again? Some people would be taken to a concentration camp and never come back. There was always a feeling of not knowing. My parents never let me go to a sleepover because they thought some catastrophic situation might happen. There were constant blackouts and water cuts, so you had to store water and keep a battery-operated radio, candles and flashlights. Protesters or police would shoot outside the house.

Basically you couldn’t trust anyone. You had to be very careful, mind your own business, go to work or to school, then go back home. At around 9pm every day, there was a curfew to keep people under control, so very similar to what we’re living now. It was way more violent, but the routine was very similar.

How did you come to use electric light as your primary medium?

When I started making objects, I began to mix something functional with something artistic, very connected to design, but more like making a sculpture, which could be shown in non-artistic places. It was connected to the historical context in Chile at the time because there were very few spaces to show art, and they were very conservative and not open to younger artists.

It was the end of a generation but they still weren’t open to a new generation, so I was trying to find other places to show my art, like the lobby of a building or the living room of a friend. You had to make your art part of the architectural spaces.

Then one of my ideas was to make lamps and use the electrical systems of places because the only way to show art was to make it functional. The idea was basically to make a sculpture, but a subversive one. It looked like a lamp, but was a sculpture. Then I turned to making installations. We really opened the idea of a new generation of young artists, and galleries started giving us opportunities to exhibit. Then I started using the gallery’s electrical circuit in my work.

Is it important that all your works make a political statement?

It’s not very important. What is important is that every work is almost a criticism of the previous work I made. I make a piece and then the next piece is a comment on the previous piece. That’s how I keep creating.

I don’t look for political problems to make a new piece. I’m very focused on the process. For example, when I was making the Homeless Lamp trolley, what I was really interested in was how to make a moveable sculpture. Previously, I was playing with the idea of furniture, between furniture and sculpture, and then I said, “What if these pieces move?” Then the trolley opened millions of other meanings.

I think once you do something very well with a material, the meanings will come. This logic also gives you a lot of freedom because you just say, “Today, I’m making a chair, and what’s the opposite of a chair?” Then you look for another object that can make sense in that logic, and you make the object.

You create optical illusions of infinitely receding space or the impression of sound in silence. What do you like about challenging the audience’s sense of perception?

The interesting part about being an artist is that you’re like a magician – you suddenly show people that it’s possible to make art with something that they never thought of. The biggest challenge is to make them think in a different way. The key moment is when they don’t understand how the work is made. It challenges their perception because they start imagining things and their creativity starts flowing.

Then you realise that your art is triggering something in people’s minds. It’s very hard for me to be interested in pieces that give you an answer right away. I’m more interested in something mysterious that makes people question. I’d rather leave my work more ambiguous because that’s the only way to challenge people. Otherwise it’s like reading a newspaper.

What do you like about subverting everyday objects like chairs, tables, doors, ladders, fences and shopping trolleys from their original function and transforming them into instruments of power, control and surveillance?

I made a large piece called Totem completely out of fluorescent lights. Conceptually and formally, this work is very similar to the Water Tower series from 2013. Both are a representation, or more accurately, an interpretation of an existing object with a specific use in everyday life: a surveillance booth and a water tower.

Their scale makes people think and behave as if they were objects with a “real” function, yet they are entirely new objects, inventions full of metaphorical meanings. In both cases, and with smaller objects as well, like stepladders and tables, the original function is subverted and in its place is a sculpture that makes people think about what they are looking at, and consider the possible new meanings for these objects once they are transformed into art.

How do you choose the words you use in your works?

My work is all about playing with language and words on a visual, sensorial level. It’s very close to the Concrete Poetry tradition. I especially use mirror reflections with light to make the words repeat endlessly in order to have a confrontation of their meanings. It reminds me of the old-fashioned school punishment when a teacher made a student repeat the same sentence or word 100 or more times. By the end of the punishment, the repetition turns into a meaningless mechanical process.

In your retrospective at CentQuatre, what were the main themes you were trying to express?

My work explores many topics: architecture, furniture, optics, music and language, among other things. A couple of years ago, I started a series of maps; they are different ways of representing the territory of the world three-dimensionally, like the piece Sediments. I also became interested in constellations or sky charts, basically the invented visualisations of the universe in order to understand its magnitude, which is, conceptually, related to what I have explored in works related to the dictatorship in Chile: ideas of social control and surveillance.

For your Galerie Templon exhibition, why did you decide to create works related to cosmic landscapes and celestial phenomena during the COVID-19 lockdown?

Basically, I returned to handmade production. My work is more known for its minimal appearance and the use of industrial materials. Now, since I have been restricted to working with different fabricators, I decided to do as much as possible with my own hands.

During the beginning of the pandemic in 2020, I collected images of different nebulae taken by powerful telescopes all over the world. These images are visions of the space where stars are born. The original photos show beautiful colours that are a mix of gas and dust in the universe. I think of the film Nostalgia de la Luz by Patricio Guzmán.

My main interest was to use paint. It’s part of the same idea of doing something I’ve never done. I was making minimalistic light boxes using words, and everything had to be super clean. I always had a problem with scratches on the glass that would completely destroy the piece, but then I said why don’t I take advantage of that? So I started experimenting by scratching mirrors, painting and staining, and then I realised that they looked like nebulae, the sky and constellations.

The idea was to create little devices, three-dimensional paintings, that look like pieces of space, but fake. Of course, I’m interested in social and political issues and how art can be a response that permeates everyday life, and I mean outside the context of an art institution. I believe in art that is a genuine response to human activities. For example, for me, any survival strategy – ingenious, inventive resourcefulness – is in itself a form of art. That is my deepest source of inspiration. Art is a way to subvert reality, and that can take you in different directions whether escapism, confrontation or both.

Why do you choose to live and work in New York?

I moved to New York in 1997 because I wanted to live outside Chile. I stayed there because I found an interesting job when I was 25 years old: I learned how to restore furniture. After seven years doing that, I started to show my work regularly all over the world. Today, I have a nice studio where five people work with me. We make many projects at the same time or sometimes we focus on one. We fabricate most of the works in the studio. I’ve worked with the same neon fabricators for 15 years: Let There Be Neon.

What do you hope to achieve through your art at the end of the day?

For me, art is not activism; its effects are long-term in society. The process of change is too slow and complicated to be perceived in the short term. I like to think that my art might have an impact on people probably way after I am dead. For now, I’m just experimenting and guessing what it means to do what I do.

What new projects are you currently working on?

I just published the new monograph Welcome focused on my public artworks. I’m also working on a very large installation for the Paris metro that will open to the public in 2026. It’s based on the names of stars that can be seen from the Earth with the naked eye. Every time a new star is found, it usually gets a name connected to the geographical place of its discovery. The piece is made out of 300 light boxes with names in different languages.