The current edition of the Bangkok Art Biennale tackles the critical challenges facing Mother Earth in a wide-ranging event titled Nurture Gaia. Dr. Brian Curtin from the curatorial team talks to Jaz Kong about the power of art to inspire new ways of thinking and seeing the world around us

The Bangkok Art Biennale (BAB), which ends its four-month run on February 25, is

not only an opportunity for the city’s residents and visitors to immerse themselves in the work of 76 local and international artists. It’s also, in many ways, a barometer of our times. This point is driven home during my mid-January interview with Dr. Brian Curtin, an art critic, educator and member of the BAB curatorial team. While it was a pleasant winter day in Hong Kong, it was surprisingly chilly in Bangkok – and chances are climate change played a big part in the unseasonable weather. As it turns out, it also played a big part in the selection of this year’s BAB theme.

“Nurture Gaia draws its inspiration from the maternal figure of Mother Earth, symbolising her historical expressions as a nurturer and giver of life across cultures. Conceptually extending upon this, the Bangkok Art Biennale will explore vital contemporary themes such as anthropology, collectivism, ecology, feminism, and the politics of time and place,” reads the official press release. “The ‘Gaia Hypothesis’ proposes that the Earth functions like a living organism that supports life across organic and inorganic matter. Today, we face urgent issues such as climate change, pandemics, war and environmental destruction caused by humans. There is a growing realisation that humanity, as an integral part of Earth, is facing critical challenges.”

This is not the first BAB to be held after the pandemic, but taking reference from previous editions titled Beyond Bliss, Escape Routes and CHAOS : CALM, Curtin attributes the current theme to BAB artistic director Prof. Dr. Apinan Poshyananda’s aspiration to work around how to manage in difficult times.

“Nurture Gaia reminds us to take care of the Earth,” he says. “Especially post-COVID, we’ve realised how precious our existence is. Such viruses, et cetera, can come from nowhere. But BAB also touches on a lot of different themes, such as ideas about feminism, about Earth as a type of goddess. It touches on decolonial theory, the idea of retrieving knowledge from the past that has disappeared, and technologies and ways of thinking about the Earth. It’s also about religion, shamanism and more. It’s about ways of thinking outside our very rationalised or very scientific world, which seems to be causing problems.”

According to Dr Paramaporn Sirikulchayanont, another member of the curatorial team, “It involves environmental issues and how every part of the society is related. The idea of listening to others, to voices that have never been heard, to those micro narratives are brought in to encourage the audiences to reconsider these possible layers of meanings through each artwork.”

Also see: Winners of the 2025 SAG Awards

There are several distinctive features of BAB. For one, it’s the only biennale in the world with an open call. Another is the venue. BAB happens all around the city, with locations including museums and institutions, malls, residential and commercial areas, and temples. For example, there’s a Louise Bourgeois Eyes sculpture in one of the most popular temples in Bangkok, Wat Pho. Curtin agrees it offers an interesting interplay between the artworks and the places they are displayed.

“It’s opening up a relationship between secular thinking and more religious thinking, and to wonder about the forms of knowledge that belief, ideology, superstition and religion can offer us” he says. “Religion’s got a very bad reputation at the moment, but there might be something there – or just belief, ideology and superstition again. I think it opens up that dialogue with the more secular concerns of art.”

And more specifically about Bourgeois’ work, especially when some might find her breasts-like sculpture out of place at a temple ? Curtin believes it also gives “new ways of thinking about the form of the female body. We have a new way of thinking about goddess imagery. It gives her work a certain aura.”

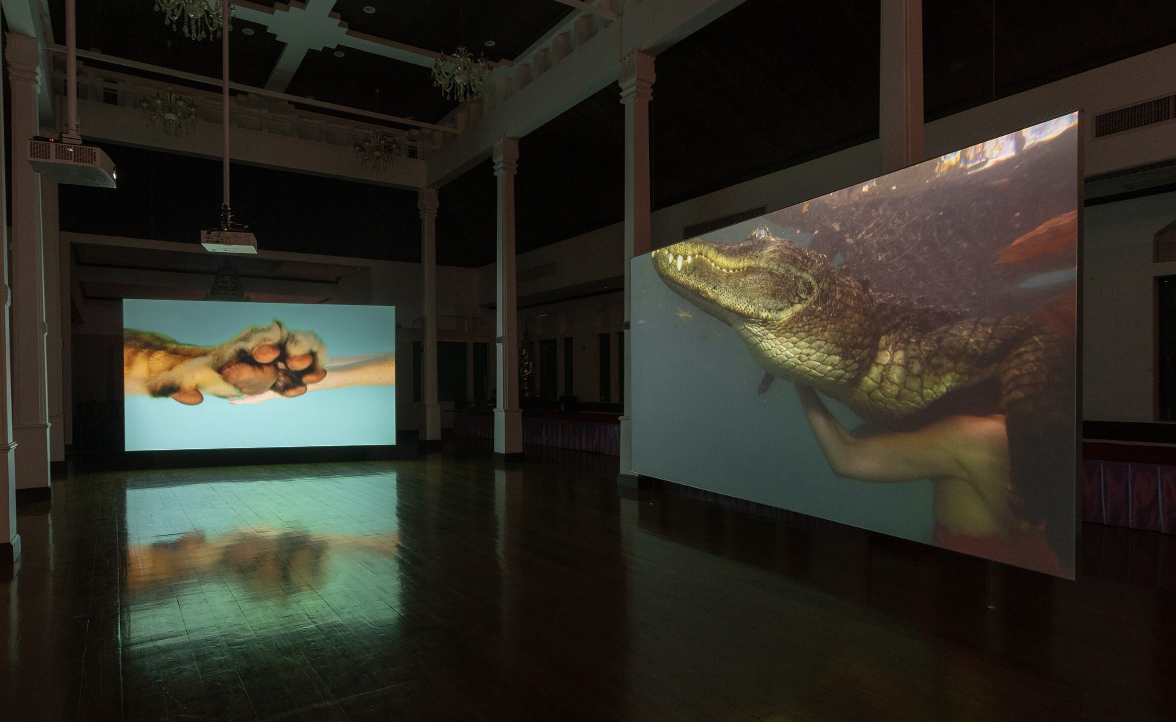

Take Jessica Segall, another artist hand-picked by Curtin, as an example. Her video installation is shown in a basilica, which Curtin says comes from Greek or Roman and forms the basis of a Christian church. “But it’s in the context of a Buddhist temple,” he says, referring to the display site of Wat Prayoon. “So you’ve got that sort of layered experience, and then Segall pushes it in another angle. It’s like a devotional quality – giving the work a certain aura of being devotional. It also plays around

with how the meanings of spaces are not fixed, and they change through time.”

Segall filmed herself dressed up in a hyper-feminised manner and swimming with alligators and tigers in (un) common intimacy. “Because in certain states in America, you’re allowed to own large predators privately,” explains Curtin. “So there’s that sort of precariousness that something could go wrong at any time. On one hand the work is very metaphoric, but on the other hand it does go into the idea of how we would establish a relationship with animals, especially predatory animals.”

This work, alongside Susan Collins’s video works LAND and George Bolster’s beautiful tapestry work The Impermanence of Protection: Big Bend National Park,

are some examples of Curtin’s curation style. “I didn’t want big metaphorical statements, like how bad the world is and such,” he says, “but it’s about giving audiences resources to think about the world.”

The choice of artwork and curation at the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre (BACC) is likewise bold and mind-provoking, while remaining friendly to all ages (such as a rather comedic video of a crowd of “termites” marching and demanding equality). The National Museum Bangkok offers another great example of changing our views about society and gender with Daniela Comani’s enlarged poster works of newspaper clippings describing violent crimes committed by women in a relationship.

“They’re based on originally violent crimes committed by men. And Comani changed the gender of the protagonist in the articles. But it also means thinking about what happens when you provoke somebody or when you provoke the Earth, when you provoke the environment. It does hit back. So it did fit with the theme in that respect.”

It would take days to see all of BAB, and Curtin appreciates the fact that everyone will get to experience it in their own distinct way. “I like the idea that everybody gets a fragmented experience of an exhibition. I think that speaks more to the way we live our lives, and it allows the artworks to maintain a certain integrity in and of themselves.”

Curtin argues there’s an urgent need to see art and really think about it, particularly of the “bold” variety. But when asked what he considers to be the meaning of art, he says, “Art is not politically accountable. It can’t be. It can’t solve the world’s problems. It can provide you with ways of thinking about them. It can open dialogues between different issues and different relationships. I don’t think it can do much more.”

Also see: Art Central reveals programme highlights for 2025 edition