For the launch of its Code 11.59 collection, Audemars Piguet celebrated in Taipei and Shanghai – and this new collection of watches, having been in the works for more than half a decade, deserves all the fanfare it’s been receiving

There’s no doubt that the unisex watch has caused a great deal of commotion within the high-end watchmaking industry – and the new Code 11.59 collection addresses that issue head-on. “At Audemars Piguet, we constantly challenge ourselves to push the limits of craftsmanship,” explains Jasmine Audemars, the watchmaker’s chairwoman of the board of directors. “Endowed with a strong spirit of independence, we proudly own our roots and territory, daring to combine precision and creativity. Faithful to our legacy, we continue to evolve by preserving and rewriting traditions. Code 11.59 is ahead of the game, constantly on the brink of tomorrow.”

This new collection blends a contemporary and a classic look, staying true to the classic round face, but with a twist. There are 13 references in Code 11.59, including five complications and six calibres from the latest generation. The spirit of the collection is represented in the name “Code” – an acronym for challenge, own, dare and evolve.

At the Taipei New Horizon shopping complex on April 11, a celebratory event showcased the 13 references alongside historical pieces from the brand’s museum. Seeing both the old, historical pieces alongside the new collection allowed for attendees to truly see the history of Audemars Piguet and how far it has come since being founded in 1875. Seeing the range of watches also shows how versatile the brand is, having produced collections that include sporty models, classic and traditional timepieces, ladies’ jewellery watches and one-of-a-kind creations.

Two weeks later, the second celebration for the launch of the Code 11.59 collection happened on April 25 in Shanghai at the Expo-I Pavilion. At the event, guests were taken through an “immersive journey” to the birthplace of Audemars Piguet – the forest of the Vallée de Joux. To reveal the collection, a troupe of dancers put on a show “embodying the encounter of present and future,” with esteemed attendees including Chinese actress Song Jia and actor Yo Yang.

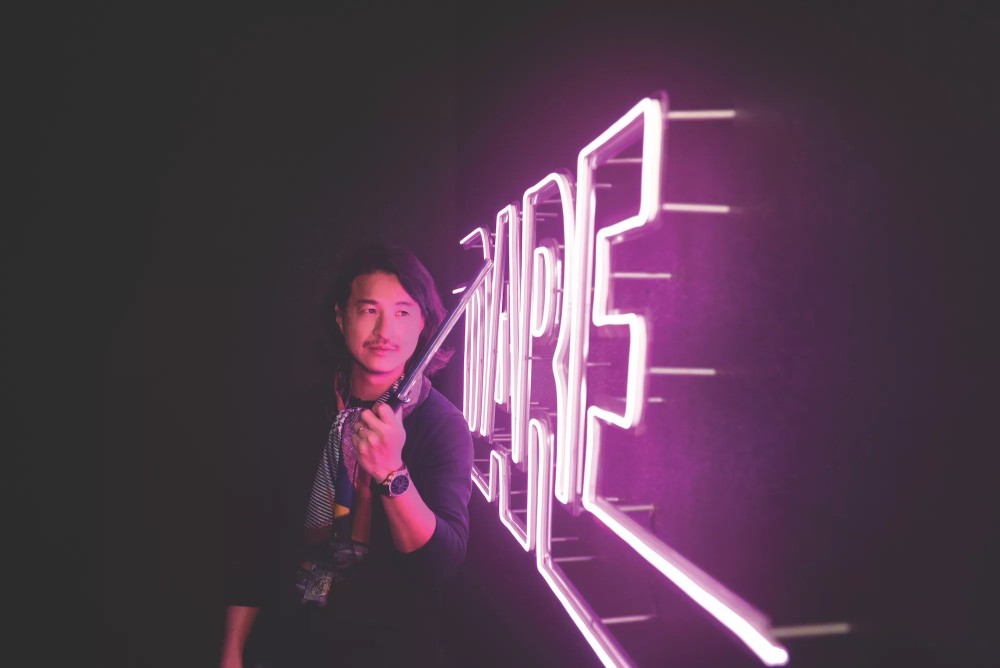

Audemars Piguet invited three prominent Hong Kong figures to attend the event in Taipei. Artist Michael Lau is widely known for his illustrations and designer toy figurines; Olympic swimmer Yvette Kong represented Hong Kong in the 2016 Summer Olympics; and May Chow, named Asia’s best female chef in 2017, is the creator of the Little Bao, Second Draft and Happy Paradise restaurants. We caught up with these three impressive individuals in Taipei and got some insight into why the watchmaker selected them as the embodiments of the Code 11.59 collection’s spirit.

Michael Lau

Audemars Piguet has recognised you for your ability to own and evolve. How would you interpret these words?

I really like how the brand interprets “own” because it comes from family values. Audemars Piguet is not just a big conglomerate and I can really relate to that, since as an artist, I have always been on my own – like a one-man band. So everything I do belongs to me. The human side of the brand has become something that I really treasure. In terms of “evolve”, in my creative career, I have always tried to break away from what I have done before. But at the same time, when I do something new, there’s always something carried over from the past, which is how I believe the brand is interpreting “evolve” in terms of this new collection.

Do you see a similarity between your work and the brand’s spirit?

First, the values such as “own” and “evolve” are something that we have in common. More importantly, the art Audemars Piguet produces is what we have in common. The watches are art pieces – just like what I make. Whenever you create something at the highest level of quality, it becomes art. The watches, for men or ladies, like my artwork to my collectors, are pieces of art, but

also toys – something you can enjoy and have fun with.

To those seeing your work for the first time, your pieces might be misinterpreted as toys for children. What would you say to those people to allow them to fully appreciate your art form?

With the kind of work I do – specifically figurines – I never think of them as toys when creating them, but as art. Figurines are just one of the mediums through which I express my creativity and art, and I leave it to the audience to decide whether it is a piece of art or a toy. It’s up to the audience to create their own definition, because art is supposed to make you think and ask questions. I don’t want to force the audience to define what I do.

What is your concept of age?

Even though I’ve reached middle age, I still think of myself as a kid, which allows me to create the kind of art that I do. People see a sense of humour in my art. I don’t think that you should define yourself by physical age, but by what you perceive inside. Another thing I find interesting with the journey I’ve been through is that I have always been a child at heart. This has enabled me to express this serious topic in a not-so-serious manner.

What has been the most difficult challenge you’ve faced in creating your work?

The biggest challenge is when I’m working and want to express my creative ideas, but I can’t get past the feeling of being tired and wanting to go to bed. No matter how much I want to create, I still have the duty to my body to get to sleep – I can get over all other challenges.

Who is your legend?

This is a question I’ve seriously pondered for a while. There are a lot of inspiring people, but I’m not sure if I would define them as legends or just someone I look up to. I would rather develop myself into the legend.

Yvette Kong

Audemars Piguet has recognised your ability to challenge and dare. How would you interpret these

two words?

To challenge the limits for me is just an endless quest for perfection. And to dare is to have firm convictions and to stick to it, no matter what. I very much identify with those two words.

Do you see a similarity between your profession and the Audemars Piguet spirit?

Yes, I think being a professional swimmer has a lot of similarities with the brand’s spirit. When I was seven and I watched the Sydney Olympics, I set the goal and challenge of going to the Olympics one day. I was so mesmerised by the swimmers on TV. I started out on the school team and then moved up, increasing my training hours year by year. I was doing quite well, with a pretty perfect trajectory, and beginning to break Hong Kong records at 13 years old. Then at 16, I climbed up to the top 30 in the world. After all this success, I ultimately had a six-year plateau. During those six years, I trained every day and even increased my training hours, but unfortunately, I didn’t improve at all. I sort of went slower. I was very frustrated and retired.

So you actually retired?

Yes, I did. I missed the Olympics in 2012 by 0.1 second and then in 2013 I was done, so I told my coach that I was going to try a normal life in college and take some spare time to do other hobbies. After a while, though, I missed swimming. I realised that going to the Olympics was an unfinished dream that I needed to complete. I also realised that I had been running away from my problems. I sought out professionals to talk through my problems, as well as friends and teammates. I am really grateful to have them. I slowly came back to the pool with better well-being and more focus. I did some reflecting and learned that in the past, I was overlooking what made swimming so enjoyable – like hanging out with friends, life lessons and all that – and was too fixated on the results. Once I came back with a new mentality, I was so much happier at training. I graduated from UC Berkeley and then I went to Edinburgh for a new start, with a new coach and a new diet, and made the Olympics. I even reached the A-cut, which only about 40 to 50 people in the world make.

People had been telling me, “You can only swim slow for so long,” which was five years by then – like, “Come on, you are not going to drop six seconds all of a sudden in a year and make the Olympics.” I did something beyond imagination because of my firm convictions and support. I knew my capability; all I needed to do was buckle down and believe. Every day, I was this woman on a mission – that’s how my coach would describe me. I kept trying out different things, analysing every small detail in my stroke. Since time is the best judgment in swimming, 0.1 seconds can make or break a dream. So I missed the Olympics by 0.1 seconds, but I actually made the Rio Olympics by 0.1 seconds. For me, the notion of time, each little detail, and having the conviction and will to challenge something, really resonated with my story.

How did you get into swimming?

I started swimming when I was about three. All my cousins swam; they were all older boys and I wanted to be part of the group. I wasn’t a natural at first, but then I got better in those YMCA classes. Going into the water, that sensory feeling when water is going past my body, that flickering sense… I kind of fell in love with it. I always tell people I was a fish – my first email was Yvettethefish at Hotmail! I was just completely obsessed with it and every day I couldn’t wait to go swim. It was such a happy thing until I was labelled a little prodigy after breaking the Hong Kong record – then the expectations began to build up. That’s when it went from pure joy to a burden. I was fixated on the results and I just needed to break away a little bit. I had to find that little girl that enjoyed the water, come back to the pool and renew my mindset.

Do you have any other hidden talents besides swimming?

I have practised martial arts since my early teens. It was serendipity. Fate had me meet my sifu [master]. For most Chinese martial arts, there are hundreds of movements in a particular set. One time I got eight movements, which is quick to learn, so I decided to focus on Wing Chun kung fu. When I started swimming seriously, it helped my back muscles and helped my coordination – the physical technicality side of it. When I reached that six-year plateau in my life, it helped me with the mental and emotional side of it. Wing Chun is about precision and the ability to control every little movement. So for me, the deep synchronisation between the brain, mind and muscles, forced me to be grounded. That’s one of the many great life lessons it taught me. Now that I’m 26, I want to spend the rest of my youth in martial arts. I am doing it because I want to repay my master and what Wing Chun has done for me. I think without martial arts, there wouldn’t be the swimmer sitting here now.

How do you see Hong Kong’s overall athleticism as a city?

I think it has changed a lot over these past 10 years. I saw the 2009 East Asian Games in Hong Kong as a turning point, since it was the first major games held in Hong Kong. After that, we got more media attention and funding for sports development, and overall a heightened sense of awareness for sports and a wider culture of athleticism. It’s not only developing for athletes, but you also see more people running and cycling on the streets, and kids are being sent to learn different kinds of sports. I think it’s going in a positive direction.

Growing up, there was not a lot of media attention or support for sports. When I was in school, my swimming was kind of against my teacher’s will. I would get yelled at and be told to spend more time studying instead of swimming, but of course I went with my passion. I would have loved it if my teachers and classmates were cheering for me. I think that’s definitely changing now, which is a good thing and I’m really happy about it.

What is your ultimate goal, personally and professionally?

Personally, I just want to be independent, someone with integrity and someone who is fun-loving – you know, someone who’s a joy to be around. Professionally, I think I’m still young, so there might be multiple careers ahead of me. But in whatever career I do, I wish to adhere to high standards. Whatever I do, I hope and wish that I can have a positive impact on society at large.

Who is your legend?

Definitely Bruce Lee. Growing up, I loved watching his movies and I resonate a lot with his talks about water, because I like water – and the whole philosophical thinking around being in the flow. The attitude “be like water” is a great attitude for life. These three words are an endless inspiration for me.

May Chow

Audemars Piguet has recognised your ability to evolve. How would you interpret this word?

I would interpret “evolve” as constantly challenging myself as a person in what I am doing, in my passions and my career. You can see this when we were doing Little Bao. It was really successful right away, gaining international awareness, so that by the time we were going into our second and third year, people kept asking if we wanted to do another Little Bao or a hundred Little Baos. As much as that was a compliment, that wasn’t what I wanted to continue to pursue. My passion was to constantly revisit the idea of Hong Kong culture, Chinese cuisine and its history, and then evolve it into something new with a personal interpretation.

When I finally opened Happy Paradise, I did move forward to open a hundred Little Baos because it was a personal challenge to see how I could reinvent the story without losing the traditions, pushing the different angles. It’s not about doing something new, but thinking about what it came from. I was able to evolve as a person once I understood Chinese traditions and what it represented in the Chinese culinary world. I think that’s what Audemars Piguet and I have in common. They could have continued with their Royal Oak range, but instead chose to reinvent themselves and challenge themselves, continuing to deliver excellence throughout the past 144 years.

Do you see a similarity in your work when compared to the Audemars Piguet spirit?

I think so. When you’re in your own space, you have the very great privilege of having your own history of excellence – and at some point, you’re just competing with yourself. It’s not whether someone required you to do it; it’s not that society doesn’t accept you for who you are today, but it’s about a personal need to progress. It’s not about how great we were yesterday – it’s about how great we will be tomorrow. I’m not impressed by myself today because I’m always looking at something tomorrow.

What challenges did you face when you got your start in the culinary world?

When I started six or seven years ago, it was simpler – it was just purely to break through, to do something to give me independence and my own voice. It was about knowing that in the local culinary culture, there isn’t someone who is just local, but someone who understands the international food flavour profiles and can integrate it into Chinese culture, having something very cohesive for Hong Kong and Hong Kong only. That came very naturally. As the years went by, however, I started to question whether I was really unique internationally. I didn’t like the idea that people were coming into the restaurant saying that my restaurant reminded them of something. I started to feel that I wanted more individuality and didn’t want to be compared to anyone, necessarily – I wanted to be this unique entity not just within Hong Kong, but in the global community.

So we had to set new goals to not be on-trend, but ahead of trends. We wanted people to look at us for the answer to the question: “What is the future of Chinese food?” That was a new goal. But of course when you have goals that big, you set yourself up for failure. You don’t realise that when you are fighting for creativity at that level, no one understands it. People first came in expecting to see a Little Bao 2.0, but it wasn’t Little Bao 2.0. It was completely new – people didn’t even know whether to like it or not yet, because they hadn’t grasped it. However, within two years, suddenly everyone began to understand what we were trying to do. We were trying to perfect the voice, always. So I think creativity takes time and it also takes time to communicate what you’re doing. It takes time for people to understand what your vision is, since they have already accepted you in a different form. You have to remind people that you have multiple forms, and that this is not the limitation of yourself or your creativity. Eventually, they will accept it and celebrate it. This happened with Happy Paradise; this year we were named among the best 20 restaurants in Hong Kong and Macau, and we were featured by Anthony Bourdain. We are now recognised in the international scene, like in Paris, and we are doing a lot of European tours. So compared to two years ago, there’s a huge difference.

So you’re always striving to be ahead of the curve…

It was really hard at first, but now it’s starting to gain momentum. Nothing feels better than feeling like you aren’t riding on something from before. To come back from Little Bao and create something completely new – a naive attempt with a lot of perseverance – delivers results. I think it needs to be naive because if I knew what I knew today back then, I don’t know if I could do it again. It was very, very hard, with very long hours and a lot of changes, full of all the sacrifices you have to make for creativity and passion. Since I’m always naive about the spirit of creativity or daring to do something different, after a few years you get rewarded spiritually for the efforts. I was able to put my own voice on the culture and Chinese culinary map, in my efforts to add a footprint to the whole culinary journey. That’s something I’m very proud of and excited about.

What’s the next evolution you see?

I think it’s constantly changing. Now I see the taste of the intellectual thought of food and I’m starting to recognise that it’s not about doing something trendy, but finding concrete value in representing Chinese cuisine. People like to see fusion; people like to put it into those terms. We don’t want to get muddled in with everyone else in terms of what we’re trying to do. Now we are evolving. Most Chinese restaurants might be creative, but they’re still all about taste and evolving recipes, or continuing the traditions of Chinese cuisine. We want to preserve that as well, but we want to do it at an educational level. We want to see if we can work with professors at the University of Hong Kong to analyse the ingredients of availability across China. Can we understand the anthropological way of the historical map and the Chinese diaspora around the world?

There’s so much stuff to know and for me, it’s not a personal wealth of information – it’s about learning this information and sharing it with everybody. It’s not as common in China because when you have personal wealth of knowledge, it’s about retaining it for your family, or maybe for your children, so they can gain wealth from it. But for me, it’s more about: “We had the Cultural Revolution and we lost a lot of content within our society – how can we return and preserve it?” We are at the cusp of a very amazing time in China and we want to be able to contribute to it. That’s my next goal.

If you weren’t a chef, what do you think you would be doing?

A watchmaker! No, that requires too much attention to detail – I couldn’t be a watchmaker. What would I do? I think I would definitely be creative. I would probably try to be an artist. I would do art that makes you scratch your head and ask, “What’s that about?” I didn’t learn about art until much later in life, but now that I’ve been exposed to it, I’m very intrigued.

Are you ever surprised by your success and popularity?

I had a unique personality at the right time, at the right moment. It helps to be a woman right now, having a voice, being a female chef, being part of the LGBTQ+ community. Thirty years ago, I would have been stoned for everything I’m saying, but right now it’s being celebrated. I can’t take credit for Little Bao because I’m really smart or something – it’s because I had a vision that’s right for this time and period. That’s why with everything interconnected, it has catapulted me to a certain level that I wouldn’t have had if it wasn’t at this moment.

Your face is arguably just as famous as your bao. How do you feel about that?

I don’t think I’m famous. I think it’s funny when people come to my restaurant and they’re surprised that I’m there. They say, “Oh, what are you doing in the restaurant?” And I reply, “What do you mean? I’m supposed to be in the restaurant.” When I found out I won the best female chef in Asia in 2017, I really thought about whether I should take the award. I really considered for a night if I should go up and accept it or not. I decided that if I was going to have a face and a voice that I wouldn’t just speak about myself – I would talk about women’s issues, or LGBTQ+ issues, or social issues, or whatever I could put a light on to create positive change for our society. So if people recognise my face, that’s great, but I don’t want to be famous for the sake of being famous. I think that was a turning point. Actually, I thought I was going to do social work much later in my career path, but these opportunities happened. So I clearly realised that I had to do this earlier. So I literally took my face and voice and presented it to different communities. I told them, “Hey, I have this voice and this face – what do you want to do with it?”

Who is your legend?

So many, but recently I love [Nike co-founder] Phil Knight. He is an extraordinary person and I think – similar to Audemars Piguet – having a vision for five decades really shows that it’s not down to good luck. It takes vision and perseverance, and not corroding your vision over time, which is a very hard thing to do. You can do it for a decade, but five to six decades – that’s a different type of person.

Also, Jane Fonda. Every decade is a reflection of what you will do. I tell people we’re going to live until we’re 150, so don’t give up life at 60 – you have 90 more years to go, so if you give up at 60, it’s over. Jane Fonda said, “If you asked me at 80 if I was going to have an award-winning show on Netflix, I didn’t even know what Netflix was.” Having that open-mindedness means amazing things can happen at any point in time. That’s the spirit I would like to maintain for five or 10 decades.

Story by #legend