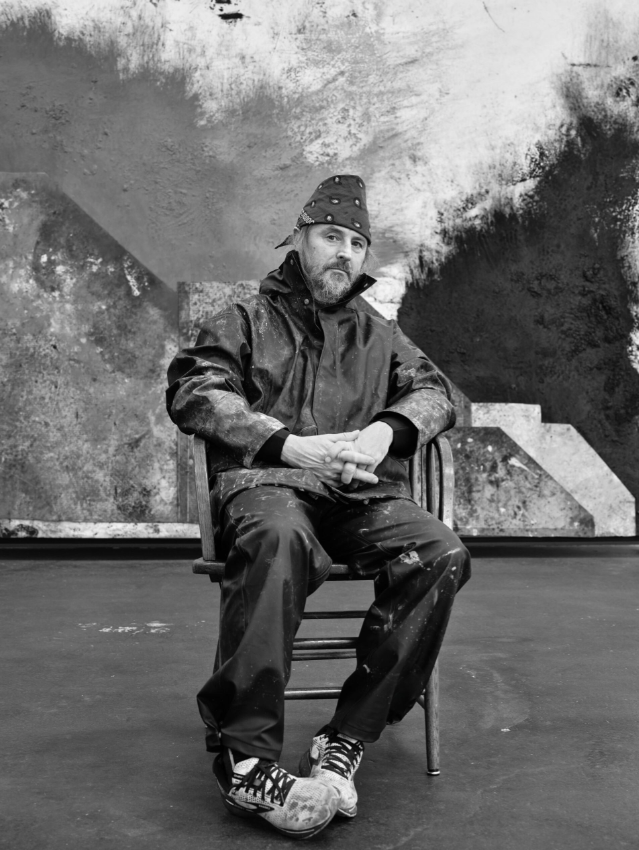

Los Angeles–based artist Sterling Ruby returns to Gagosian Hong Kong with an examination of verticality. He talks to Jaz Kong about building things up while always being on the brink of losing balance

While it’s been 10 years since Sterling Ruby’s last solo exhibition in Hong Kong, which also marked the artist’s debut with Gagosian, it doesn’t come as a surprise that he remembers the city’s skyline as well as its hallmark hustle and bustle. What’s unexpected are the smaller details he remembers, including the black window frames at the Gagosian gallery on the seventh floor of the Pedder Building. The frames are almost a geometrical reference to Ruby’s works, or more accurately, a false mirror to his paintings.

Ruby, who holds American and Dutch citizenship, and lives and works in Los Angeles, is in town for the opening of his new solo exhibition at the gallery that runs until March 1, 2025. Simply titled | – as “an ode to verticality” – the show features new paintings from his TURBINE series (2021–) that stand in stark contrast to his VIVIDS series from 2014. Whereas VIVIDS was marked by tilted and angled horizontal lines, the works in TURBINE are “flipped” 90 degrees but still give viewers the same imbalanced uneasiness, making them question their perspective of the world (or perhaps whether they should have their eyesight checked).

Indeed, one thing that remains constant for the 52-year-old Ruby is his exploration of the intersection of sociopolitical histories with the narrative of his own life. Recalling his VIVIDS show, he says, “It was still abstract, but they were spray-painted straight out of a can, and each one had a horizontal line. During that time, I’d been thinking about it in an existential way. Looking at the horizon, is it the future? Is it the past? Is it dark? Is it bright?” With the slanted horizontal lines, these questions persist; the only thing we can be certain of is change – which brings us to the TURBINE series born three years ago.

According to the gallery, which presented Sterling Ruby: TURBINES in New York in 2022, the new series has the same root in terms of materials as the artist’s earlier WIDW paintings (2016–), whose title is an abbreviation of window. “The series is named in reference not only to turbines and windmills, but also to hurricanes, explosions, fires and war,” read a description by Gagosian.

The animalistic crawl-mark resemblance is a revolution to the WIDW series, suggesting that “rather than observing the action through a window, the combination of oil paint with bright cardboard swatches is tumultuous, as if a storm has blown the window apart and set its elements in motion.” The raw energy can be recognised by the intersecting diagonals breaking geographical boundaries with cardboard components blasting across the canvas.

Two years later, Ruby has brought a more subtle yet disruptive show to Hong Kong, with his previous visit to the city inspiring his creative process. “I remember this space from 10 years ago having the pillars and these black window frames, giving a lot of geometry while also having a lot of verticality,” he says. “So I wound up thinking specifically about that in terms of the way that it would look in this space and this architecture and the city. I’m from Los Angeles. We don’t really have a city – it’s just a big sprawl. And I’ve always loved looking out the window in Hong Kong at these massive skyscrapers and everything being so vertical and monumental.”

Each of the 10 paintings on display focuses on the precarious state of a central form confronted by an explosive action and teetering on the precipice of downfall. This latest series is also an ode to Hong Kong, as Ruby describes our city as “influential to writers, science fiction and filmmakers. I always think of Blade Runner and the synthesis that Ridley Scott made in the film – I love that. I love the continuity of thinking about a city, how it looks and how it’s being influential to people who do things creatively with it.”

However, much like Scott and his all-time classic, what Ruby sees is not a perfect world. The vertical structure in the paintings is cardboard collage on a canvas filled with layers and layers (some scratched out on purpose) of oil. “I tend to make paintings on the ground, and I’d start dying each canvas starting with one colour. The next step is to peel them on the ground. The floor in the studio is always covered in cardboard, and then I wind up cutting out pieces while I’m working on the paintings,” he explains.

“Another thing to stress is the fact that they are collages. I tend to work on both (painting the canvas and cardboard) at the same time and when they come together, they’re a painting but they’re also a collage. The era when collages were first introduced by Kurt Schwitters or Picasso, they were perceived as this higher form of art. There’s this notion of the illicit merger – things that were never necessarily meant to go together being forced together by this new genre.”

What’s telling the story of Ruby’s dystopian world is perhaps not the how, but the what. At first, the | works give a Scream-type vibe, as if the vertical line in the middle is breaking the paintings in half. Ruby points to TURBINE. En Saga. as an example, saying, “Things are really about losing balance in very didactic forms. Most of them are just two strips of cardboard on top of a painted ground. And I just wanted to make this very definitive nod to collapsing, to falling, to being on the brink of losing balance. And so each one is like a painting inside of a painting, and this one is shaped like a katana, which is a samurai sword.

“It wasn’t the thing that propelled me into that shape, but when you look at the more squared or geometric base, which is almost like a pedestal, and when you look at the more contoured top, there’s something about the curve of it that, like, it ruins to fall apart. So I’m trying to push that idea. I want it to feel like when you look at these, even though they’re very basic or very simple, I want each one to have that uneasiness that things are not stable, just by creating something very simple, very didactic and very formal.”

While these newer TURBINE paintings may seem more structured, more calculated, more humane even than those shown in New York, there’s still a sense of hidden chaos – imagine the high-rise buildings around us getting demolished, how something seemingly so gigantic and so permanent can be gone in a blink. This came from a part of Ruby’s personal history that he rarely told anyone before this show (except for those who are very close to him).

“When I was young my father worked as an explosives technician,” he says. “He was a contractor who worked for a company with other demolitionists. He worked on old buildings, old factories and old smokestacks. I went with him on a number of different occasions. It was so long ago but it’s always been with me, the memory of collapse that has been a biography of experience as a child and how it impacted me.”

While Ruby is well-versed in the way things can fall apart, he’s also committed to building things that last. Case in point: he makes all the frames for his paintings. “I used to use a framer but I was never happy with how thin the framer could go. So during Covid, I cleared out a section of my studio and we bought an entire frame-making shop,” he says. “We bought equipment that was almost the nicest digitised equipment that you could buy to plane wood and to do joinery. It’s not ‘bespoke’, but I want it to feel like a [piece by famed woodworker George] Nakashima, like a cabinet or something like that. It’s a very subtle thing. And we try to make them as thin as possible without tweaking. So maybe if you don’t know it, you wouldn’t look for it. For me, it really is part of the work.”

One could say it’s poetic to use something so immaculately made to contain a story or history that stands for chaos. “To me, it’s very important that everything is controlled. I like these kinds of extremely contrasting things,” Ruby says. “The perfect frame is like a type of institution, almost like a prison. So when you put something so dark and so gestural inside this perfect frame, it’s like being in prison, you know? Like there’s intention associated with it.”

Ruby’s intention with |, it seems, is for us to reconsider our notion of verticality amidst our fractured reality. As the show notes remind us, “Formally and socially, verticality defines integrity. Historically a measurement of excellence, it is associated with progress, status and respect. It is also, however, subject to collapse.”