The rooster is the 10th of the animals the Chinese use to denote each lunar year of the traditional 12-year cycle. It is a common motif in Chinese art, in part because the Chinese word for chicken is a homophone of the word for auspicious, making the rooster a favourite subject. Sometimes the fowl is depicted in a straightforward way. Often it is depicted more teasingly, and in the works of artists Tang Yun and Gao Jainfu, it is barely discernible.

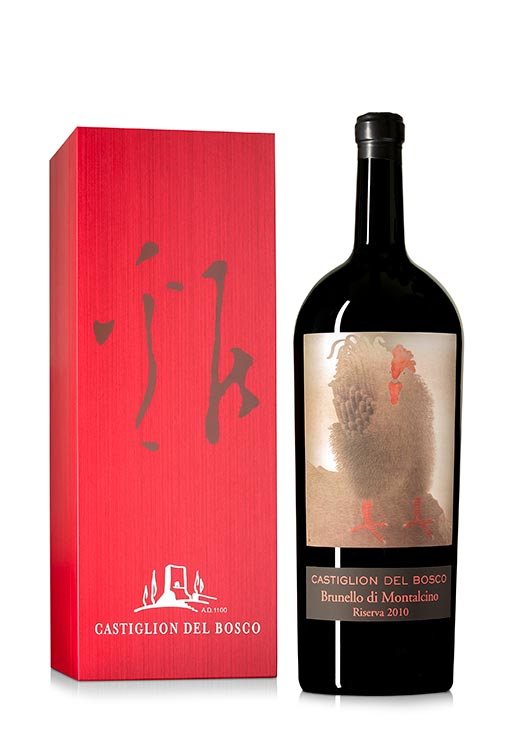

When Tuscan winery Castiglion del Bosco asked Beijing-born artist Shao Fan to paint a rooster to adorn the label of its limited-edition Brunello di Montalcino Riserva DOCG 2010 Zodiac Rooster, Shao had to make a choice familiar to Chinese painters but a choice that might not occur to Westerners.

Shao’s oeuvre combines the literati school of painting which is noted for its abstract style, three-dimensional art and furniture design. Some examples are in the permanent collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. His stock in trade is rabbits, of which he has painted more than 40, rather than roosters but he accepted the commission offered by the Italian winery that is owned by Massimo Ferragamo’s Ferragamo USA. “I thought my earlier work, which was more abstract, would be more suitable,” says Shao.

He did several paintings showing just the top half of the bird. “Then Massimo and the winery thought it would be more suitable if I did the rooster in its entirety, so it looks more exaggerated, with the rooster’s comb.” So what was the point of painting only the top half? “There was more humour doing it that way,” Shao says. “It’s a little more humanising in such a style. There is more of a connection.”

When Shao draws or paints a rooster, he has no recognition of how the bird is represented in Western art. Picasso, Buffet and others often painted the rooster in a somewhat comical light. “I don’t know the associations the rooster has in the West,” Shao says. “I don’t know what that culture means.” Shao’s point of reference is how he paints rabbits. “The best way to explain the rooster is by recalling periods of my rabbit painting,” he says. “I’m not painting a rabbit, I’m painting a human. I don’t just want to depict a real-life rooster on this label. It’s more literati-style than that.”

The rooster has associations for Westerners that are different from the associations it has for Chinese, so Westerners may struggle to interpret Chinese representations of the bird as the artist intended –just as they may find it hard to understand much of Chinese art. “We always put a chicken or rooster with a dog,” says Shao. “We have a very old saying, ‘A dog and chicken together are not quiet.’ The chicken is descended from wild birds but is domesticated. So the chicken is closer to humans. The dog is descended from wolves, but has also been domesticated, so it’s also closer to humans.”

The rooster is more like a bridge, therefore, between wildlife and humans. “It’s very close to human lives,” he says. “Even though a chicken is far from being human, we feel somehow close to it. I don’t know what that means in Western culture. But in Chinese culture we always praise the chicken.” He points out that, in Chinese art, roosters are always associated with gentlemen.

“We think the rooster has five gentlemanly ways of behaving,” he says. “First, it has good morals, as it’s the earliest riser in the morning. Second, it keeps its feet on the ground, so is very courteous. Third, when chickens eat, they always eat together, not on their own. They are very convivial and communal creatures. Fourth, roosters are also very brave. They are often fighting. In fact, they like to fight. And fifth… oh, I’ve forgotten the fifth point.”

Although he may fail to understand it fully, Shao has been influenced by Western art. “Do people follow art or does art influence people? For me, Western art is modern art, like Duchamp. So much work is done with so much energy and inspiration, and in bursts. It is like a firework, or water spilling from a bowl. Everything spills. It’s fulsome. I feel Chinese artists, about 200 years ago, had a big, deep jar full of water. But we just shook it a little bit and the water is a tiny part of the creation.”

As a multidisciplinary artist, Shao constructs chairs as well as he paints rabbits or roosters. “I follow the Chinese cultural tradition,” he says. “Nowadays, people separate everything clearly. Let’s go back 200 years. Chinese scholars had several skills. They could write good calligraphy, write a poem. They could paint. They could play instruments, play chess, do kung fu. It’s a kind of very unique offering. Also, they could design gardens or their own architecture. It was, like, a Chinese cultural tradition, a very extensive reach in terms of cultural accomplishment. But nowadays, that range of accomplishments doesn’t seem to exist in the West and it doesn’t seem to exist in China.”

Shao shares the belief that Chinese landscape art is in crisis as modern painters make the art form less and less familiar. “Landscape in Chinese art is always a symbol for elements of something else and it has become modern today,” he says. “The crisis in landscape today seems to be both real and artistic.”

The thought elicits another observation: “With modern art, so much is appreciation of the ugly, so it is appreciation of oldness. This kind of appreciation exists only in China. The Chinese understand oldness very differently from Western civilization. In China, we appreciate oldness. Oldness is good in China. Also, when I made this painting for wine I never tasted, it’s like a kind of old-style thinking, a kind of alchemy.”

Never having visited the Tuscan winery or tasted its wine is no handicap. “Being an independent artist, most of the time nobody gives me restricting projects. I usually create what I want,” Shao says. “This time there was a frame and I welcome that limitation: the frame and its unlimited freedom. From that point of view, I thank Ferragamo for giving me this frame. Kung hei fat choi.”