In 1830, artist Eugène Delacroix painted La Liberté guidant le peuple (Liberty Leading the People). Now displayed at the Louvre in Paris, the painting was inspired by the July Revolution of months prior and featured, among other things, the physical manifestation of the concept of liberty, set against the background of the Notre Dame cathedral. The tricolour flag held by the female figure was initially a symbol of the French Revolution and would go on to represent the French nation-state.

Revolutions, social causes, riots and protests have often gone hand in hand with painting, poetry and the rest of the arts. For example, in 1572, François Dubois painted his depiction of the St Bartholomew’s Day massacre of the Huguenots – the Protestant minority in France – by French Catholics. William Cowper wrote anti-slavery poetry for the late-1700s Abolitionist movement in Great Britain. In the first half of the 20th century, Chilean poet Pablo Neruda wrote about the political upheaval in Spain and France. In more recent years, modern and contemporary conflicts are represented by way of street art, photography, video art, murals and so on – really, any visual medium available.

Protest Graffiti in Khartoum

In late 2018 and early 2019, the African nation of Sudan saw mass protests against autocratic president Omar al-Bashir, who had been in power since 1989. Al-Bashir is currently on trial for “possessing foreign currency and acquiring suspicious and illicit wealth”. The protests received backing from the military, which ousted al-Bashir from office in a coup d’état on April 11, 2019. The initial expectation was that the military would then hand power over to a civilian government after holding elections. However, the citizens of Sudan quickly realised that that wasn’t going to happen anytime soon.

The military were quick to tighten their grip on power and began carrying out systematic crackdowns in the capital of Khartoum against pro-democracy demonstrators. Sudan, a country where a number of human-rights violations have been occurring over the past years, had its African Union membership suspended due to violence against protestors that has left hundreds dead and many more injured.

Walked through the site of the #Khartoum sit-in this afternoon. Murals painted by the protestors are all that is left… pic.twitter.com/rzUWbVkddR

— Tom Wilson (@thomas_m_wilson) June 9, 2019

During the protests, dozens of murals and other forms of street art popped up in Khartoum. The art itself usually draws on traditional imagery and incorporates the colours of the first Sudanese flag of the 1950s, when the republic first achieved independence. The artists use the walls of the city to criticise other countries for not acting, or for supporting the military instead of the people. In a nation with more than 100 different ethnic groups, some artists choose to explore the diversity in the population, while others use #Sudaxit to convey their desire to withdraw from the Arab League. Some depict faceless men and women, representative of all of Sudan, while others use 22-year-old student Alaa Salah, who became a protest icon in the country.

I’ve been seeing this pic on my #Sudan_Uprising TLs today and it’s amazing. Let me tell you why. pic.twitter.com/Gt6Otvj0Al

— Hind Makki (@HindMakki) April 8, 2019

These pieces of street art are not the work of one or two artists, but rather the work of numerous people who see this as a way to convey discontent about the way their country is being governed.

Badiucao on Extradition in Hong Kong

On June 16, 2019, a record-breaking two million people marched in Hong Kong against the extradition bill that is being proposed by Chief Executive Carrie Lam. The march, which lasted more than seven hours, as well as all the protests leading up to then, have received widespread international coverage. The bill itself is a highly unpopular piece of legislation in the Special Administrative Region that would allow for Hong Kong to extradite people back to jurisdictions that do not have formal extradition agreements with the city; the list includes Mainland China. Protestors believe that the bill would allow for critics of Beijing to be detained and extradited to the Mainland, and that it would be extremely detrimental to freedom of speech in Hong Kong.

Before protests on the June 12 turned violent, Hong Kong cartoonist Badiucao released a new poster for the anti-extradition-law rally. The poster features a single protestor standing in front of what appears to be a tank. The symbolism here is quite apparent, drawing on the famous “Tank Man” picture from the 1989 Tiananmen Square Massacre, and also pays homage to the 2014 Umbrella Movement with the presence of the yellow umbrella in the figure’s right hand. The poster was posted on the website for the Hong Kong Free Press and is still available for download.

Since then, the artist has released more images relating to the events that have taken place, including Lam’s apology and the death of the “Raincoat Martyr”. Badiucao has been labelled a dissident Chinese artist or an artist-provocateur, prompting comparisons to Ai Weiwei and Banksy. As a result of the nature of his drawings, he has also been in conflict with the government in Beijing. His art, simplistic and primarily digital, can be seen on the HKFP website.

Replication and Incarceration of the Kurds

In 2016, Kurdish artist Zehra Doğan was imprisoned on terrorism-related charges in Turkey for replicating a photograph of apparent clashes between the Turkish army and the PKK – the Kurdish Workers Party. The armed conflict between the Turkish government and the Kurds began in 1978 and continues to this day. The Kurds are an ethnic group of 25 to 35 million people in Turkey, Iran, Iraq, Armenia and Syria – making them the fourth-largest ethnic group in the Middle East. Yet, since they are spread across five separate sovereign nations, they remain classified as an ethnic minority in their respective countries. The Treaty of Lausanne, signed to conclude the First World War, removed the possibility of a separate Kurdish state from the table. As a result, there are several Kurdish separatist movements that exist in each of the above countries; the Syrian Kurds have gained considerable attention due to their contributions in reclaiming ISIS strongholds.

In the early part of the 20th century, the Turkish government banned Kurds living in Turkey from practising their culture after uprisings against the government by the ethnic group. The Kurdish language, names and clothing were all banned. In 1978, the PKK was formed to continue the struggle for a separate nation. The group armed themselves, and the clashes between the Turkish forces and the PKK has led to thousands of deaths since then, resulting in the Turkish government banning the PKK and labelling its offshoot groups as terrorist organisations. But where does an artist fit into this?

Zehra is imprisoned because she drew a painting of this famous photo. The court calls the painting “terrorist propaganda” pic.twitter.com/JEaUcXTumf

— Zehra Doğan (@zehradoganjinha) July 5, 2017

In 2016, after the failed coup against Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, a state of emergency was declared in Turkey and there was a crackdown in the southeastern part of the country against the Kurds. A photograph that was taken of the scene was recreated by Doğan, and she was put on trial in 2017 following her initial detainment. While Doğan argued that she was simply recreating a viral image, she was charged with spreading propaganda by the Second High Criminal Court of the province of Mardin, where she living at the time. After spending nearly three years in jail, she was released in February 2019.

The painting features houses with Turkish flags hanging overhead; Doğan stylised the Turkish tanks as mechanical monsters that scoop up the residents of the town of Nusaybin, where the incident took place. While it is a recreation, Doğan’s own commentary shines through loud and clear. To this day, she argues that the commentary fits in with her work as a journalist, for which she received a Metin Göktepe Journalism Award for her coverage of Yazidi women escaping from ISIS captivity.

Bansky’s Satire and the Bethlehem Wall

The foundations of the French Revolution were laid in underground meetings in Paris, when members of the Enlightenment began discussing the monarchy and how it treated the people of France. But the initial signs of rebellion were already present on the streets in the form of posters and pamphlets. One could argue that the act of expression in a public space is mysteriously safe – provided one remains anonymous and the origin of dissent cannot be traced back to them. Such are the circumstances surrounding street artist Banksy.

Banksy originally began in graffiti as a teenager in the 1990s and adopted a pseudonym to protect his real identity. While many know him for his work that attacks capitalistic structures and corruption in politics, he also has a series of works that draw on prominent political issues. In the 2000s, he travelled to the Bethlehem Wall, a separation barrier in the West Bank that is the subject of great controversy in the Israel–Palestine conflict. Many of Banksy’s works about the geopolitical issue, nine of which are painted along the wall, draw on the political history of the region.

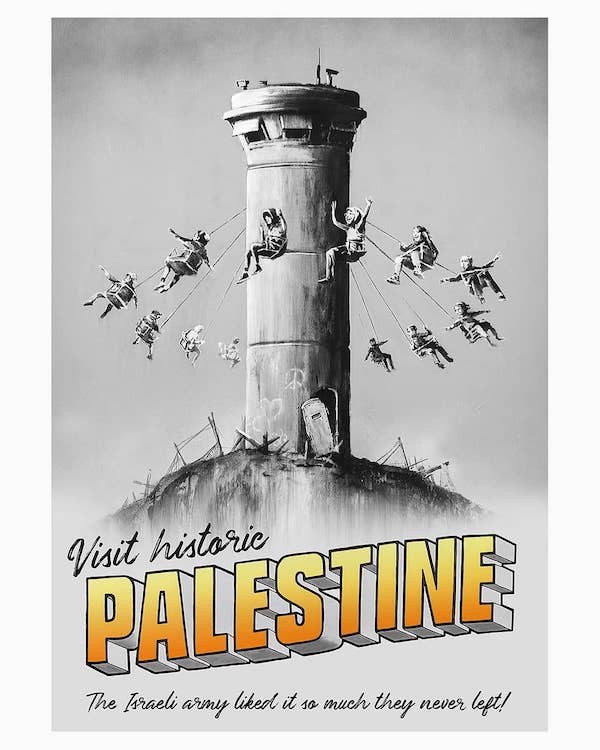

The works use satire to convey their meaning, much like the poster above. Made in 2018, the piece sums up Banksy’s views on the polarising conflict while also referencing the 2016 UN Security Council Resolution 2334. The poster was released on Banksy’s Instagram page shortly after both sides exchanged fire in November 2018 and following the protests staged by Palestinians along the Gaza Strip in October of the same year.

Like a touristy postcard, the poster uses Banksy’s signature black-and-white stencil art. The watchtower-like structure functions as a carnival ride for the figures, who appear to be enjoying themselves, oblivious to the chaos and destruction on the ground below them. The poster is a classic example of the artist’s use of political satire.