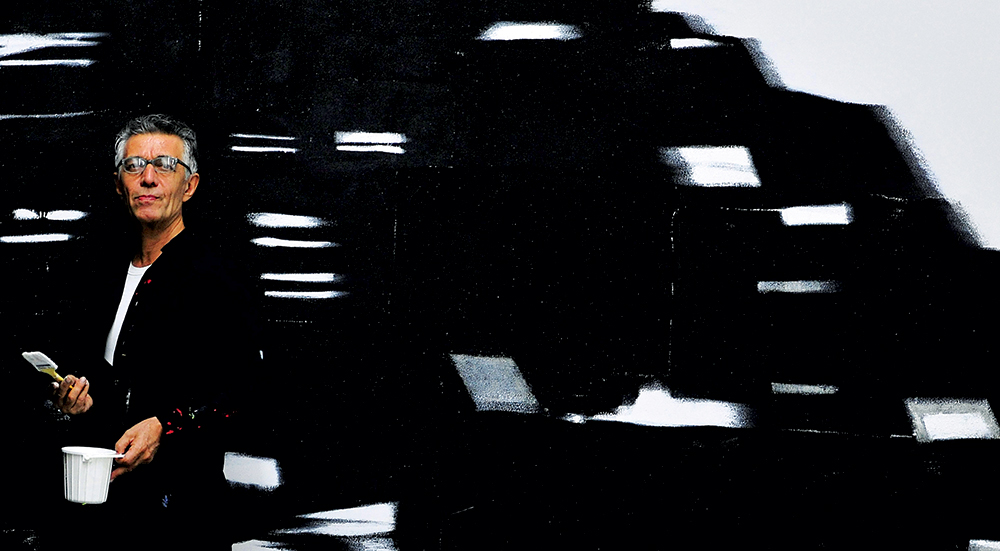

Reza Derakshani dandies his way into Sotheby’s S|2 gallery in Hong Kong like a svelte, italicised exclamation mark of style – a perfect rendition of Iran’s Yves Saint Laurent. And by his side, a young Russian ballerina, a principal dancer in Moscow, stands impossibly erect, statuesque, artful. Wherefore, Mr Degas? He would have deliquesced over this sublime mise en scène. Derakshani and his current muse make the most canvas-able art couple imaginable, as electric and ecstatic as Giovanni di Nicolao Arnolfini and his wife in Jan van Eyck’s 15th-century game-changer The Arnolfini Portrait.

Derakshani has good reason to be living in the moment. With his inaugural Hong Kong show, Sotheby’s is presenting its first Middle Eastern art exhibition anywhere in Asia. No sooner was the Iranian’s work being hung on S|2’s walls than Art Basel announced the presence of Iranian gallery Dastan’s Basement at its Hong Kong event, to be held from March 29 to 31, 2018. Remarkably, the Tehran-based space, which focuses on young and emerging Iranian artists, will mark the country’s first-ever representation at any Art Basel event.

Middle Eastern art – despite current resistance to such categorisations in the art world, be they gender- or-nation-specific – has been gaining considerable recognition on the international stage of late. It’s also been catching the eyes of Asian collectors, whose tastes have started to broaden beyond traditional Asian and Western artists.

Sotheby’s has combined the 65-year-old Derakshani’s work with the late sculptor Alfred Basbous (1924–2006) and taglined the show Two Moderns from the Middle East: Reza Derakshani and Alfred Basbous. The former presents 15 new oil-on-canvas works, with 12 bronze and marble sculptures from the latter.

Two Moderns from the Middle East has been curated by Arianne Levene Piper and Eglantine de Ganay-d’Espous. “Over the last few years, there has been a marked growth in interest for Middle Eastern art from collectors in Hong Kong and Mainland China; the idea of a show in Hong Kong therefore came about quite naturally,” the pair remarks.

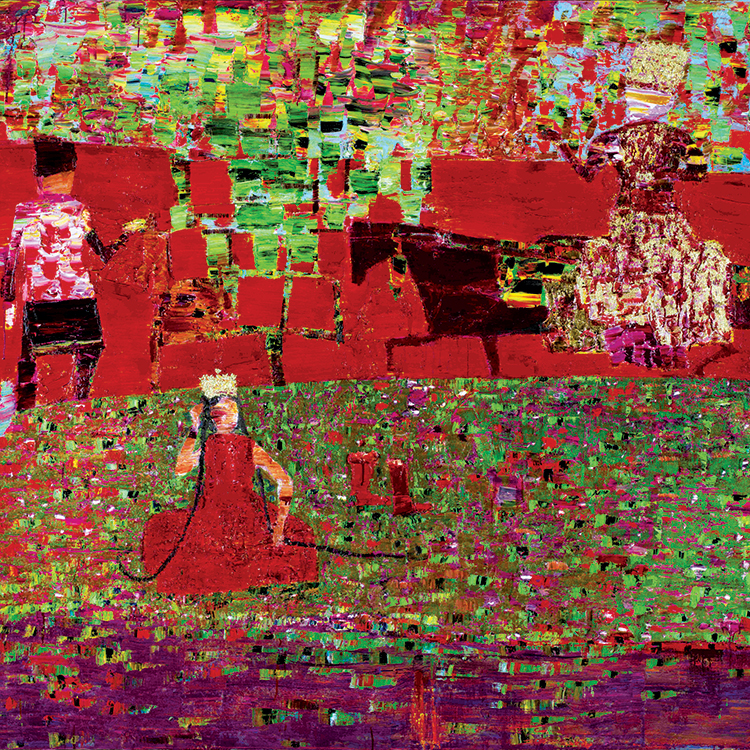

Derakshani has produced an array of stunning canvases for his baptismal solo show at Sotheby’s. Spectacular hunter scenes in “Derakshani Red” complement more nuanced compositions in earthy tones, grey and even mild pink. His works can be abstract, figurative, fauvist and neo-expressionist, sometimes all within one work. Due to his use of colour, he’s become known as “The Red Artist”, but has this tagline or epithet been agony or ecstasy for him? “The Red Artist, or The Artist of Red – I like the idea,” says Derakshani. “Red is the most energetic and powerful colour for me and I have mastered many ways of making that colour even more vibrant.”

Surprisingly, Derakshani’s work can feel somewhat Chinese-influenced on first viewing. “The main characteristic of my work is versatility,” he says. “I have done series that do not connect to my cultural heritage directly, but the works here at Sotheby’s are in fact from series inspired by Persian miniature paintings. My guess is that the similarity between traditional Persian art and Chinese work is what gives you that connection.”

If there’s a certain “sass” to a Derakshani canvas, it may spring from his coverage of hunting scenes that appropriate the story of Bahram Gur, or Bahram V, a Sasanian king who ruled from 420 to 438CE. In the era, surfaces had varied contours and were decorated with vivid colours; often they were partially gilded using a mixture of mercury and gold. Symbols of power and prestige, these vessels were often presented as royal gifts to persons of importance within Iran and beyond its borders. Large numbers of them have survived from the time of Sasanian rule in Iran and Mesopotamia, demonstrating an Eastern tradition that spread westward to the Hellenistic and Roman worlds.

Hunting also defined a ruler’s attributes of strength, skill and mastery of the natural world. The horse became an animal of paramount importance in the Near East, especially after the 20th century BCE; a defining moment came with the invention of the war chariot in the 17th century BCE. Horses and chariots were among the most prized commodities in the elaborate system of royal gift exchange at the time.

Derakshani is a painter, poet, musician, performance artist. Born to a nomadic family in Sangsar (a small village in northeast Iran), he was heavily influenced by the beautiful rural landscapes of the surrounding Khorasan region – brimming with roaming horses, lush mountains and colourful fields of flowers. Derakshani was painting at the age of 9 and, by 20, had risen to prominence with a solo show at the renowned Ghandriz Gallery in Tehran. After graduating from the University of Tehran in 1976, he furthered his studies at the Pasadena School of Art in California before returning to Iran to teach at his alma mater and the School of Decorative Arts. Following the Islamic Revolution in 1983, he left Iran once again and ended up living in New York for 16 years.

During his time in New York, Derakshani befriended the likes of American art heavyweight Cy Twombly, Italian contemporary artist Francesco Clemente and Iranian visual artist Shirin Neshat, and has derived his personal style by blending abstract and figurative elements. He has been influenced by Twombly, of whom he observes: “He shared with me the sense of freedom, colour and childlike calligraphy on canvas. I can deeply share his feelings, standing in front of a blank canvas to breathe life into it.”

For a man who channels a confluence of references and civilisations in his work and his life, who else has influenced Derakshani artistically? “That’s hard – I try not to get influenced, but it’s inevitable. It could range from Da Vinci to Rothko,” he says, as though not wanting to reveal more – unlike fashion, about which he proclaims: “Gallivant and Alexander McQueen are my two favourite designers.”

Walking through S|2 as a viewer is somewhat like collaborating with a dance partner and learning new moves along the way. A Derakshani canvas lives – static, ecstatic and euphoric at all times – and generates rhyme and rhythm in its abstractions. We’re pushed and pulled as viewers, physically; we need to step forward and back to experience the full range of visual interplay and sensation.

It’s also in the way Derakshani’s figures or objects (faces, trees, horses, flowers, garden parties) speak of a rich historical Persian heritage, such as the epic poem of Shahnameh, so beloved by Iranians the world over. Hidden under layers of paint, surface distortions and fragmentations, we find references to a historical legacy through the eyes of a mystic, a lover of beauty who reminds us through these very distortions that what matters is the occulted memory, not the spelling out of that.

Today, Derakshani divides his time between the cities of Dubai and Austin, Texas, where, in parallel to his visual arts career, he collaborates with legendary musicians including John Densmore, the drummer of The Doors, with whom he has recorded two albums. Derakshani has also painted a private chapel at singer Sting’s residence in southern Italy.

What’s his desert-island artwork? “I guess one of my own works, because I could take it back to my studio and make transformations and it will never end and never be the same.” As for his process, and especially for the new pieces he prepared for Sotheby’s, he works instinctively. “Normally, I don’t have any pre-plans for my work – no sketches, not even knowing what canvas and how it might find a life,” he says. “I just know that I have to get into a meditative, spiritual mood – and the rest is where it takes me and whatever happens.”

This article originally appeared in the December 2017 print issue of #legend magazine